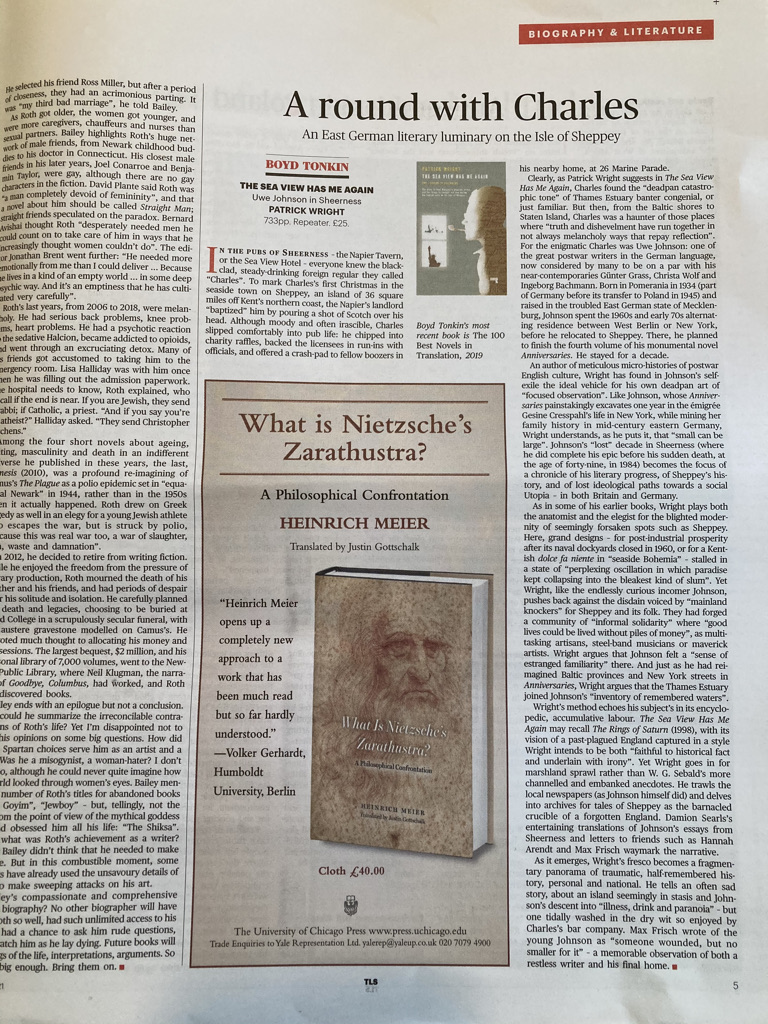

Uwe Johnson in Sheerness

by Patrick Wright

with extracts from Uwe Johnson’s Island Stories

translated by Damion Searls

London: Repeater Books, Hardback,

8 December 2020. ISBN: 9781912248759

Paperback, June 2021

See at the publisher’s site, at UKBookshop.org

Towards the end of 1974, a stranger arrived in the small town of Sheerness on the Isle of Sheppey in Kent. He could often be found sitting at the bar in the Napier Tavern, drinking lager and smoking Gauloises while flicking through the pages of the Kent Evening Post. “Charles” was the name he offered to his new acquaintances.

But this unexpected immigrant was actually Uwe Johnson, originally from the Baltic province of Mecklenburg in the GDR, and already famous as the leading author of a divided Germany. What caused him to abandon West Berlin and spend the last nine years of his life in Sheerness, where he eventually completed his great New York novel Anniversaries: From a Year in the Life of Gesine Cresspahl in a house overlooking the outer reaches of the Thames Estuary? And what did he mean by detecting a “moral utopia” in a town that others, including his concerned friends, saw only as a busted slum on an island abandoned to “deindustrialisation” and a stranded Liberty ship full of unexploded bombs?

Patrick Wright, who himself abandoned north Kent for Canada a few months before Johnson arrived, returns to the “island that is all the world” to uncover the story of the East German author’s English decade, and to understand why his closely observed Kentish writings continue to speak with such clairvoyance in the age of Brexit. Guided in his encounters and researches by clues left by Johnson in his own “island stories”, the book is set in the 1970s, when North Sea oil and joining the European Economic Community seemed the last hope for bankrupt Britain. It opens out to provide an alternative version of modern British history: a history for the present, told through the rich and haunted landscapes of an often spurned downriver mudbank, with a brilliant German answer to Robinson Crusoe as its primary witness.

The Preface

as republished on Literary Hub

Launch Conversations

USA: A conversation, with Edwin Frank, Editorial Director of New York Review Classics and translator Damion Searls, via the Community Bookstore, Brooklyn, 5 January 2021. See on YouTube

UK: “Where Might We Find a Moral Utopia?” Bristol Festival of Ideas, Tuesday 16 February 2021

Available here

“Beyond the Sea: Uwe Johnson, Patrick Wright and the Isle of Sheppey”, a conversation with Simon Matthews, the Quietus, 27 February 2021.

![Blue Town Heritage Centre, set for a wedding tea]()

Previews

“This tidal book, reaching into everything and then withdrawing to show what it left behind, is a triumph.”

— Neal Ascherson, author of Black Sea and The Death of the Fronsac

“A double ‘biography’ of the great but always tempestuous German writer Uwe Johnson and his ultimate home, the gritty and disreputable Isle of Sheppey. ‘Biography’ is in quotes because Wright is a saboteur of genres and his books encompass multiple worlds. I stand in awe of what he has accomplished here”.

— Mike Davis, author of City of Quartz and Set the Night on Fire

“Patrick Wright has written an extraordinary, haunting book, a devastating allegory of our own time, yet seen from the mid-twentieth century. Wright’s phenomenal achievement is to painstakingly set the scene against which the final volume of Uwe Johnson’s monumental four-part novel Anniversaries can be read and to turn it back to us, with a contemporary question — are we left behind or staying behind?”

— Gillian Darley, author of Villages of Vision and Excellent Essex

“An astonishing chronicle of the great German author Uwe Johnson, who moved to Sheerness, Kent in the 1970s.”

— Helen MacDonald, author of His for Hawk and Vesper Flights

“With consummate timing, when so many are locked in a blind charge towards some bigger and better crisis, Patrick Wright has picked over the landfill of a very specific Estuary culture to devastating effect. The Sea View Has Me Again is a monumental sifting and arranging of local particulars, stitched against the savage farce of a great European novelist’s elective exile. Remorseless retrievals from bunker and cranked microfilm, enlivened by human witness, make this final panel of a notable literary triptych, following on from A Journey through Ruins (Dalston Lane) and The Village that Died for England (Tyneham), into one of the abiding memorials to a tattered angel of history”.

— Iain Sinclair, author of Downriver and The Last London

“In this masterful modernist history, Patrick Wright tells the story of an island which is England, yet much more than that. Wright’s Isle of Sheppey is a de-industrialised place, not in the North, but in the garden of England; a refuge of liberties that has three prisons; a dockyard and garrison town with a pacifist MP; an island which could be destroyed by bombs left over from the war, but which far from being stuck in the past is a model for a new post-industrial world. It is the stage for an extraordinary cast of characters, among them Napoleon Bonaparte, DH Lawrence’s mother and an Anglo-Catholic fascist parish priest; the Wright brothers’ patent agent, the nation’s first indigenous aviator and the father of the British atomic bomb; the communist leader of the engineering union, an immigrant imperialist machine-tool inventor; makers of modern furniture and foreign photographers.

At its heart is the life, work, and inspiration of extraordinary East German writer Uwe Johnson who drinks himself to death in a pub run by veterans of the Battle of the River Plate. Wright scintillatingly creates, from perfectly observed fragments from the past and flashes of a better future, a British history like no other, crafted with tools forged out of hard realities of modern European history. With its steely dissing of the tide dichotomies and exceptionalist clichés which disfigure our sense of who we are, this is Patrick Wright’s most important book. It brings Europe to England by showing it has always been here, at a moment when too many want to believe something else.”

— David Edgerton, author of The Rise and Fall of the British Nation and The Shock of the Old

Reviews

“A model portrait of person and place, a kind of cultural and literary geography that never fails to fascinate.”

— KIRKUS (starred review)

“Sebald on steroids… I loved every scrap of it”

— John Mitchinson, BACKLISTED

“Beautifully written, defiantly oddball, challenging in so many ways and completely compelling.”

— John Wyver, Illuminations Media

“... a huge achievement: a comprehensive portrait of a place and a person, and the best book about Brexit that’s yet been written.”

—Jon Day, “Books of the Year”, The White Review

“The first telling of a life tends to be heroic, dramatic, and efficient. But a second telling can always be imagined, built of stories left out of the first for any number of reasons. This second, inverse telling might be arduous, indirect, speculative, and sad. It might provoke a reaction of what-exactly-is-this?, like Rachel Whiteread’s negative-space sculptures of building interiors. It might also be as valuable as the first.”

—Ben Ratliff, review at 4columns.

“Sometimes the most necessary books turn out to be the ones you didn’t realise you needed. Before reading Patrick Wright’s The Sea View Has Me Again (Repeater) I had no idea that there was a hole in my life waiting to be filled by a 750-page book about an East German writer and his ten-year self-imposed exile on the Isle of Sheppey during the 1970s. But I was entirely captivated by this microscopic, discursive study of Uwe Johnson, a pioneering novelist who crossed the Iron Curtain but declined to fall at the feet of the capitalist West, opting finally to settle himself and his family in Sheerness, apparently on the basis that it was the closest thing he could find to East Germany without the Stasi. It is also a great book about the relationship between Britain and the rest of Europe, and not a page too long.”

—“Books of the Year,” New Statesman, 17 November 2021

“I am increasingly obsessed with place as a way to understand history and the techtonic shifts in culture and society. Very few pieces of writing have matched Patrick Wright’s new book in the ability to chart, through one place and one life, the startling shifts of the past half century. On the face of it this is a book about Uwe Johnson (the under-read and perhaps under-appreciated German writer) and his life in Sheerness on the Kentish Isle of Sheppey. But, as with all of Wright’s work over the decades, it is so much more: a study of deindustrialisation and decline, a history of England and of the Kent coast, and a stunning work of both biography and literary criticism.”

—Verso, Staff Picks 2020

“If you are looking for a straight biography, then keep browsing. If, however, you are after an eccentric, brilliant, digressive, idiosyncratic, social-historical door stopper to get lost in, then Patrick Wright has produced something special. Wright uses psychogeography and psychobiography to bleed the life of Johnson through the veins of Sheerness, thus giving life to the town. In a sprawling narrative that layers the kernel of Johnson’s life, he also creates a beguiling memento mori to a place that has often been left for dead by central authorities, and a German writer who moved there from New York with (at worst) something of a death wish, or (at best) with the overwhelming burden of finishing his magnum opus Anniversaries. A best book of 2020 contender.”

—NJ McGarrigle, Irish Times.”

—Zinovy Zinic, Books of the Year, TLS, 2021

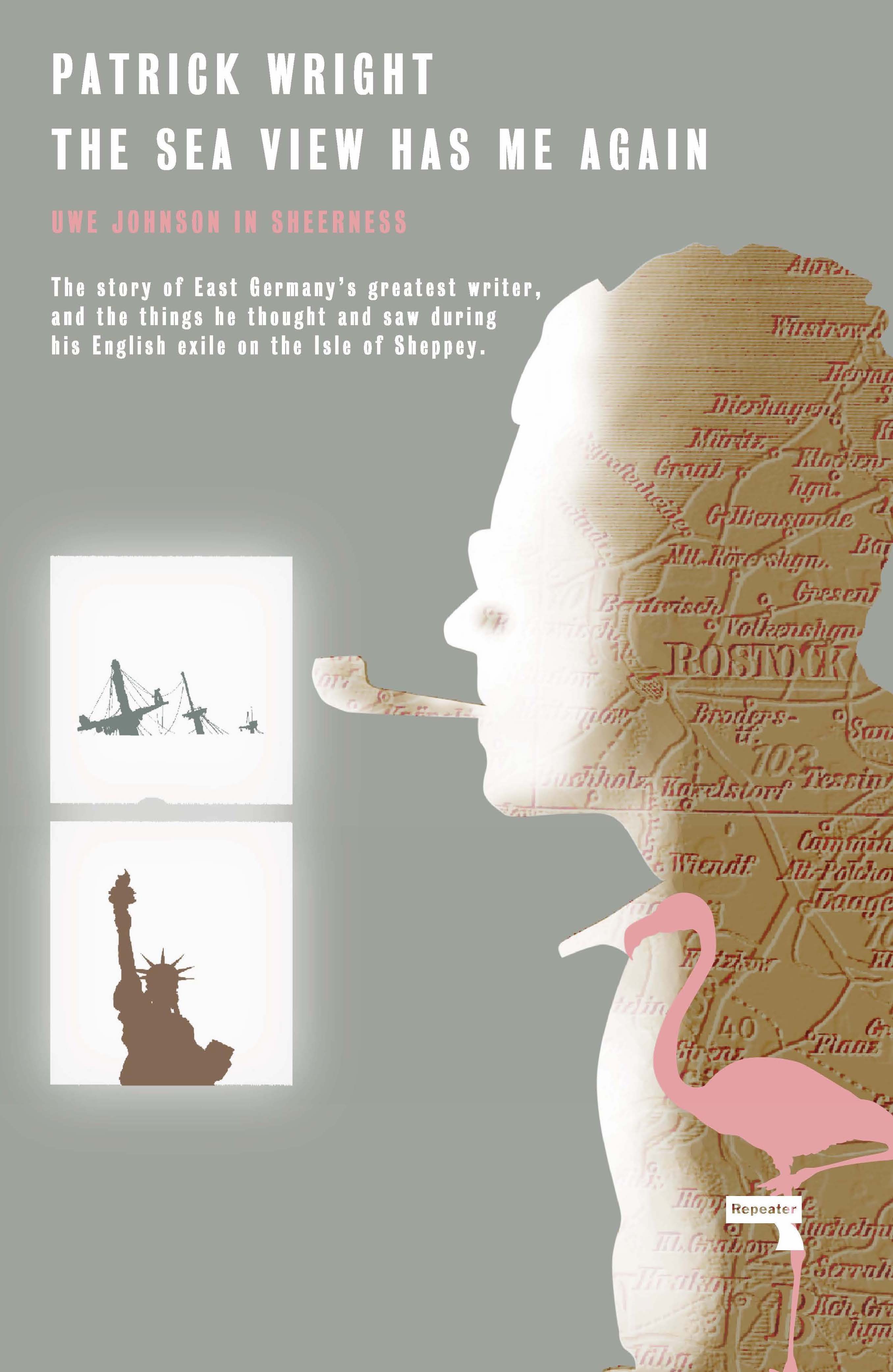

“Clearly, as Patrick Wright suggests in The Sea View Has Me Again, Charles found the ‘deadpan catastrophic tone’ of Thames Estuary banter congenial, or just familiar. But then, from the Baltic shores to Staten Island, Charles was a haunter of those places where “truth and dischevelment run together in not always melancholic ways that repay reflection’... Wright plays both the anatomist and the elegist for the blighted modernity of seemingly forsaken spots such as Sheppey. Here, grand designs — for post-industrial prosperity after its naval dockyards closed in 1960, or for a Kentish dolce far niente in ‘seaside Bohemia’ — stalled in a state of “perplexing oscillation in which paradise kept collapsing into the bleakest kind of slum’... As it emerges, Wright’s fresco becomes a fragmentary panorama of traumatic, half-remembered history, personal and national. He tells an often sad story, about an island seemingly in stasis and Johnson’s descent into “illness, drink and paranoia” — but one tidally washed in the dry wit so enjoyed by Charles’s bar company.”

— “A round with Charles,” Boyd Tonkin, Times Literary Supplement

![]()

“A hymn to estuarial peculiarity and a lament for an awkward man determined never to find his place.”

—Jonathan Meades, The Literary Review

“Reading Wright’s magnificent account we sympathize with Johnson’s plight. We

might even see the exiled German as a spiritual brother to Marvin Gaye

remembering that the singer (in an oddly similarly move) hid out in Ostend,

another backwater on the opposite North Sea shore. Both of them owlishly

looked out at the world and asked plaintively – what’s going on?”

—John Quin, The Common Breath

“. . . a glorious rabbit hole of a book. It is a longue durée portrait, from the 17th century to Thatcher, of a single location on the edges of British national life. It is also one of the most immersive evocations of the 1970s I know, fine-grained in its particularity and yet also alert to the general conditions whereby, in places like Sheerness across the postindustrial West, the midcentury economic miracle lay sedated, awaiting its death.”

Nicholas Dames, Public Books, Public Picks 2021,

“The book also doubles as one of the best-researched texts about the Island. It deals with its legends, such as Grey Dolphin; the prison hulks of Dickens; the mysteries of Dead Man's Island and Sheppey's run-in with the Dutch when Queenborough was captured by invading forces in 1667.

It includes Island characters like showbusiness entrepreneur Stan Northover who ran the Island Nightclub at Leysdown and "celebrity clairvoyant" Mia Dolan; celebrity visitors; and a painstakingly detailed account of the magnificent men in their flying machines, like Charles Rolls, who pioneered British aviation from the fields of Shellness and Eastchurch.

It also reminds readers how successive governments have left Sheppey to hang out to dry with illustrations of failed industries including the ill-fated Murad car which was years ahead of its time but ran out of road when a promised relocation loan to the Island was removed by the Board of Trade.

Mr Wright has left no stone unturned in his quest to unearth the strange allure of Sheppey and its people.”

— John Nurden, Sheerness Times Guardian

“This book is about many things: the rise of post-industrial society in Britain in the 1970s and 1980s; the ways that diverse memories and feelings can be melded into a narrative by an author to give them some kind of shape and explanatory power; the relationship between location and imagination. Finally it is testament to the ways in which writing offers a sort of salvation, even to the most blighted of souls.”

— Kerry Brown, “Uwe Johnson: The Enigma of Sheerness-on-Sea.”

“Wright’s book also rests on the subtle shaping of small-scale materials over a large expanse. The last hundred pages are particularly powerful, a final movement which begins quietly enough by introducing the note of the fabulous with the old German story of ‘The Fisherman and his Wife’.

The husband is granted wishes which his wife persuades him to inflate−to live like a prince, a king, an emperor, a pope − until she demands to live like God, and they are left again with their filthy shack. The typicallambiguous ending − have they in fact been granted their wish? Is this in fact how God lives, given the nature of the world? −leads to another marine tale, almost equally fabulous, about equally unmanageable gifts.

The SS Richard Montgomery, an American Liberty ship, sank in sight of Sheerness in 1944 with all its cargo of unexploded bombs and its masts still remain visible above the waves and its lower decks are still packed with chemicals which, as inhabitants claim and Johnson will have heard, produce fantastic lights that dance over the rigging at night.

This sets Wright in place to tell his final marine tale, after confirming that the lie of land and sea at Sheerness does indeed make the view akin to that over the Baltic from the Bay of Lübeck. This is a tale of May 1945 and the Nazis in retreat, of herding thousands of concentration camp inmates onto the Cap Arcona and Thielbeck with the intention of scuttling the ships off Lübeck, only to be beaten to the destruction by British bombers intent on denying crucial shipping to the retreating Germans, and of the roughly 8000 bodies that afterwards floated in wave after wave to the shores, where − to bring the cycle of ambiguous tales circling back, like the sweeping gaze of a watcher on the shore − the child Gesine Cresspahl finds them crowding in, as she describes in the final days of Jahrestage.

If we can no longer look directly at that opening metaphor of waves

sweeping in, ‘hunchbacked with cords of muscle’, or fail to see what is exactly literal about the final identification at the close of the fourth

volume, of walking into the sea with being on the way to the place where the dead are, Wright’s tour de force will have brought us quietly and surely back to Johnson, gaining for its seemingly eccentric enterprise a full and complete justification.’

—Max de Gaynesford, London Magazine.

‘The Isle of Sheppey which Johnson arrived in with his wife and daughter was not so different from the one Wright found forty years later: deep in cultural, economic and infrastructural neglect; prone to flooding and erosion; disparaged for its poverty, its marginality and the supposed parochialism of its inhabitants. A place of cheap holidays, ‘white flight’, potholed roads, prefabs and bungalettes, it was a stereotype of terminal England and insular Englishness: an island’s island. This one-time seaside resort, shunted aside by cheap air travel, abandoned by industry, its naval dockyard closed, tells us something about the country we live in now. It’s a place where the prefix ‘post-’ roams vampirically, looking for things to attach itself to. Wright extrapolates a history of England now, a country where the 1970s and 1980s never went away. . .

Once the reader grasps what these books [Anniversaries and The Sea View Has Me Again] are doing, they appear as masterpieces of compression and connectivity, feats of documentary imagination that have no equivalents even in the places we might expect to find them: modernist novels, Annales histories, psychogeographical adventures...’

—Patrick McGuinness, London Review of Books.

Preliminary and Associated Texts and Transmissions

“The Sea View Has Me Again” - a sound work by Patrick Wright and Shona Illingworth, Estuary Festival (first broadcast on 23 May 2021)

“The Piano Man, no ordinary scrounger,” posted on Various Small Fires 17 April 2015 (first outing of a text that has not yet been published in its final form - except at the top of the left front page here.)

“The Moral of Brenley Corner,” London Review of Books 6 December 2018.

“Turning Inward: Brexit, Encroachment Narratives and the English as a ‘Secret People.” Presented at the British Academy, 4 November 2016 and published in Ash Amin & Philip Lewis (eds.), European Union and Disunion: Reflections on European Identity, London: British Academy, 2017, pp. 64-72

“”