The Sea View

Has

Me Again:

Uwe Johnson in Sheerness

About the project and its outcomes

I first came across the writings of Uwe Johnson as a student at the University of Kent at Canterbury in the early 1970s. At that time, Jonathan Cape and Penguin were offering British editions of American translations, so we had access to the three novels on which Johnson’s reputation rested in West Germany — Speculations about Jakob (1959), The Third Book about Achim (1961), Two Views (1965) — and also the novella entitled An Absence, which I bought as published in Nathaniel Tarn’s mind-opening series of Cape Editions in 1969. I didn’t read all these books at the time, but I did take in enough to understand that Johnson was a truly exceptional writer, whose formally innovative works explored the post-war division in which both ideologically polarised German states shared the same guilty past. He was a political writer, to be sure, but no side’s partisan hack. As Jean Baudrillard had written in 1962, Johnson wrote as “an artisan of language” rather than a “manager of conscience.” Reluctant to be called an “artist”, he thought of himself as a storyteller who used fiction to get at the truth of situations. Even the design of his book plate identified him with “making” rather than lofty inspiration: it showed various different patterns of brickwork used on traditional buildings in Northern Germany.

Years later, I discovered that, in 1974, this restless and remarkable author, who had refused to shake down on either side of the Cold War division (he once declared himself on the left “but in a different spot”), had moved with his wife and daughter to Kent. Far from choosing a place that might confirm the cliché claiming this southern English county as “the Garden of England”, he opted for Sheerness, an isolated and apparently busted ex-naval town on the marshy and often windswept Isle of Sheppey, where the no longer naval river Medway flows out into the last stretch of the Thames estuary.

For years after his chaotic death there in February 1984, I assumed the story of Johnson’s English decade would one day be told by a properly qualified scholar of modern German literature. Yet no such person seemed to come along. My interest was sharpened when I realised that Johnson had actually written quite a lot about his experiences on the Isle of Sheppey. This was revealed by the appearance in Germany of a book entitled Inselgeschichten (Island Stories). Edited by Eberhard Fahlke and published by Suhrkamp in 1995, the volume contained articles, essays and more or less fragmentary extracts from letters that Johnson had sent from Sheerness to friends and acquaintances including Max Frisch, Helen Wolff, Walter Kempowski and Christa Wolf. Who could resist the discovery that Johnson had once written to the philosopher Hannah Arendt in New York, inviting her to sit with him and enjoy the sea view from the promenade at Sheerness?

I returned to the matter again in 1999, when making The River, a series of television documentaries about the Thames. Nothing positive, however, came back from the British publishers I sounded out about the possibility of commissioning an edited translation of Island Stories. The objection, which I would later hear repeated about the book I did eventually write, ran along the same lines (even when it was conveyed in silence). I was told that nobody in Britain knew or, almost certainly, cared who Uwe Johnson was. His life and death in Sheerness sounded utterly miserable. As for the Isle of Sheppey, well why would anyone want to read about a notoriously desolate place like that?

Such forebodings have encouraged me to ask myself what bearing this investigation might really have on our time with its transformed technologies, its globalised neoliberal economics, it’s defensive insularity and it’s populism. What is it about Johnson and his work that is really worth knowing to English-language readers nearly four decades after his death? And could it be convincingly claimed that the Isle of Sheppey, which had been so direly afflicted by the closure in 1960 of the Admiralty dockyard and associated naval command and army garrison at Sheerness, was more than just a deindustrialised and “left behind” backwater with nothing useful to tell anyone? Was it really conceivable that the closure had actually turned the island into an accidental testbed where the future we are living in now was already being incubated forty or fifty years ago? As for Johnson, this awkward East German Crusoe perched on the observatory he made of his bar stool in the Napier Tavern, was he actually a prescient witness rather than a blown-in and at least half-distressed foreigner, registering and also describing what happened to people when the wave of post-war social democracy finally broke and the discontents that would eventually come to a head in the Brexit referendum of June 2016 began to emerge?

It was not until I was appointed to a full-time job (my first since 1987) at King’s College London, that it finally became possible for me to find the time and resources to pursue the investigation properly. Soon after joining King’s in September 2011, I contacted Johnson’s publisher, Suhrkamp Verlag, and asked if might be possible to commission an English translation of the pieces gathered in Island Stories. They were helpful and put me in touch with the brilliant American translator, Damion Searls. He had long since made and described his own fleeting visit to Sheerness. He had also brought Johnson’s A Trip to Klagenfurt into English, and was then preparing to embark on the first full English translation of Anniversaries: From a Year in the Life of Gesine Cresspahl, a massive and, by now, award-winning undertaking which was finally published by New York Review Books in 2018. Damion was enthusiastic, so I applied to the Patsy Wood Trust, set up to make constructive use of the estate of my late cousin (an environmentalist whose parents had invented magnetic resonance scanning in a garden shed that was the beginning of Oxford Instruments). The trustees kindly provided a grant for the cost of some preliminary research as well as the translations.

There were, of course, libraries and archives to visit. There were also conversations without which I could not have proceeded: with Damion Searls, to be sure, and also with Holger Helbig and others connected to the Uwe Johnson Society and the Uwe Johnson Archive at the University of Rostock. There were diverse watery landscapes to visit and revisit too: some on the Isle of Sheppey, of course, but I also had to familiarise myself with some of the rivers, coastal spits and “backwaters” that Johnson had in mind from earlier years. I had to breathe the air of some of these places in order to grasp Johnson’s comparative and trans-national way of thinking, in which views and landscapes became bearers of memory as well as history. So I visited Mecklenburg and West Pomerania, and also New York City, where Staten Island had joined Johnson’s repertoire of evocative places.

One of the first talks I gave about my ongoing investigations took place at Aldeburgh, as part of Gareth Evans’ weekend “Place: Roots – Journeying Home”, held at the beginning of February 2013. Soon after that I started planning a 45 minute radio documentary with John Goudie, a BBC producer with whom I had worked before (on previous assignments we had stayed in a roofless house on the Hebridean island of Eigg and also in a windy Depression era hotel in Marfa, West Texas, so Sheppey was easy). Commissioned by BBC Radio Three, and made with the help of a German-speaking researcher, Helen Whittle, “A Secret Life: Uwe Johnson in Sheerness” was first transmitted as a 45 minute “Sunday Feature” on 19 April 2015. The programme, which is still available on BBC Sounds and also on other podcast sites (including Apple), attracted various interested comments after transmission. Some of the most helpful came from people who had lived in Sheerness in the seventies and got in touch to offer observations and recollections that added to what we already knew.

How though, does an outsider make meaningful contact with the residents of a town that is all too familiar with the derision of mainlanders convinced that “Sheermess” is an abandoned and dismal place on an island occupied by inbred “Swampies” with webbed feet and only two fingers on each hand? Having started out in the public library and The Belle and Lion, a new and popular Wetherspoon pub a little further along the High Street, I was pleased also to meet up with the conservationist Will Palin, who was already working towards the restoration and return to community use, of the derelict Dock Church across the moat between the town and the port that was once Sheerness dockyard. He provided me with a place to stay and also put me in touch with Chris Reed of The Big Fish, a community arts organisation in Sheerness.

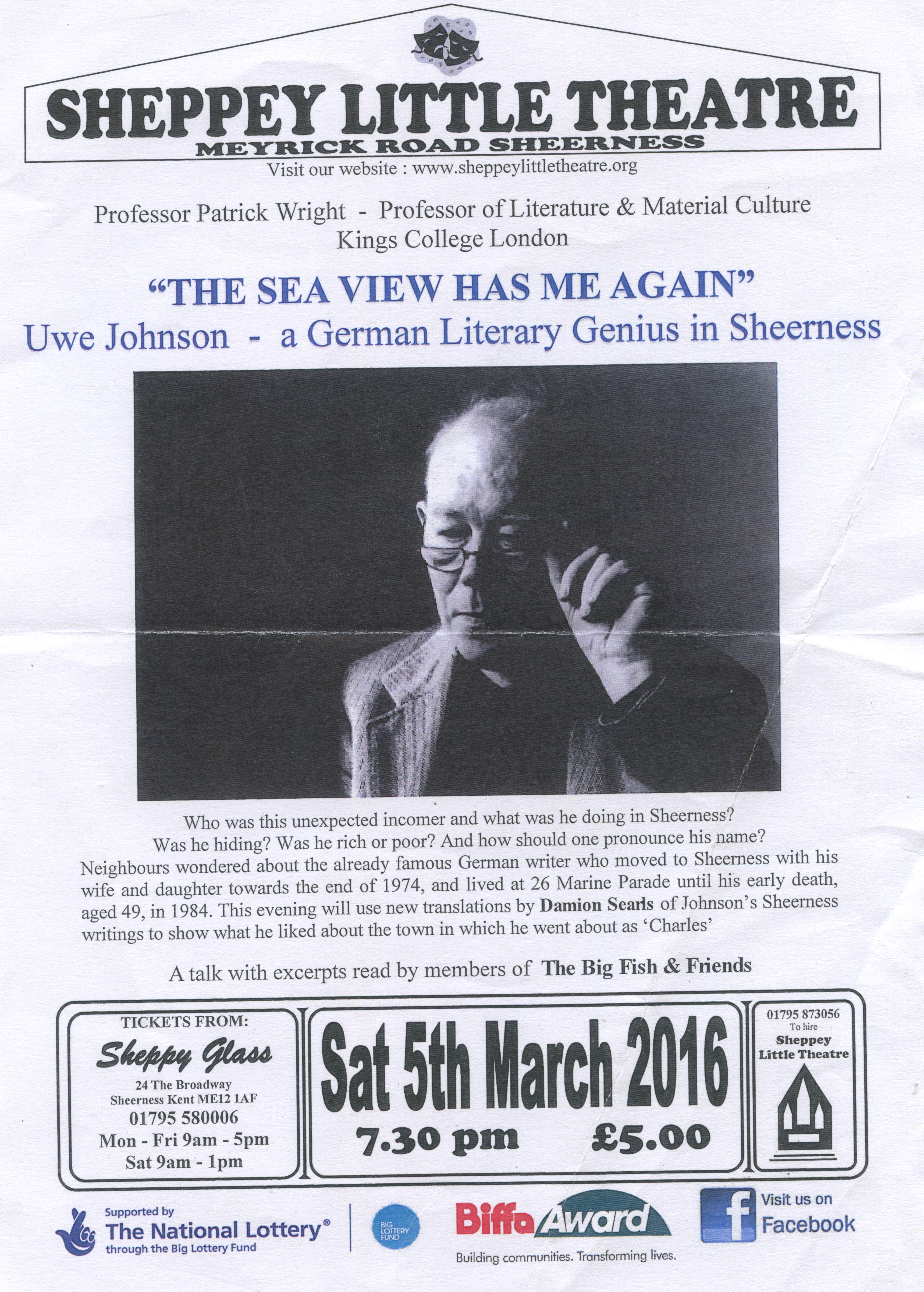

Reckoning that very few people on the island had much idea about the German writer who had lived in their town for nearly a decade, Reed and I decided to use some of Damion’s translations to change that. Having sent out the call for interested people — the group became “The Big Fish and Friends” — we initiated a series of meetings for which we squeezed into the Rose Street Cottage of Curiosities just off Sheerness High Street. Commenced towards the end of 2015, our assemblies became more like rehearsals as the winter proceeded. The outcome was an evening of readings presented together with a talk by myself, on Saturday 5 March 2016 at the Little Theatre in Meyrick Road, Sheerness. Some of our selected fragments remained as read texts. Others, including those in which Johnson had captured conversations in his favourite bars (the Napier Tavern and, in the earlier years, the since demolished Sea View Hotel), had become semi-staged performances with various props, including a bar of sorts and Johnson’s own stool, which successive licensees at the Napier Arms have been careful to preserve as a relic.I remember being told that 54 people bought tickets and pride was duly taken in the fact that this was rather more than had paid up for a Del Shannon tribute band a week or two earlier.

![Big Fish and Friends at Sheppey Little Theatre, 5 March 2016]()

![Caption: Big Fish and Friends at Sheppey Little Theatre, 5 March 2016]()

![Caption: Big Fish and Friends at Sheppey Little Theatre, 5 March 2016]()

![Caption: Big Fish and Friends at Sheppey Little Theatre, 5 March 2016]()

![Caption: Big Fish and Friends at Sheppey Little Theatre, 5 March 2016]()

![Caption: Big Fish and Friends at Sheppey Little Theatre, 5 March 2016]()

![Caption: Big Fish and Friends at Sheppey Little Theatre, 5 March 2016]()

![Caption: Big Fish and Friends at Sheppey Little Theatre, 5 March 2016]()

![Caption: Big Fish and Friends at Sheppey Little Theatre, 5 March 2016]()

The Big Fish and Friends assembled again not long afterwards, this time at the Napier Tavern, to record versions of the texts for Daniel Nash, who broadcast them on Daniel’s Monday Night Community Show on “the island’s very own truly local radio station” BRFM (“Best Radio for Miles”). This was followed by a repeat performance, not at the Little Theatre this time, but on board LV21, once the Goodwin Sands lightship but now a floating venue, which was moored at Gravesend as part of Metal’s 2016 Estuary festival.

![Jim Enright and Chris Reed of The Big Fish and Friends]()

Having learned a lot from these conversations, and others that they made possible, I concentrated on researching and writing the book that shares its title with those events involving The Big Fish and Friends. I was greatly assisted by the award of a Leverhulme Fellowship in 2015, which gave me a year in which I didn’t have to think about anything else. I must admit also to having benefitted from the first Covid-19 lockdown, which made it unusually easy to concentrate on pulling the final book together.

Finished in August 2020, The Sea View Has Me Again: Uwe Johnson in Sheerness, was published by Repeater Books on 8 December 2020.

There is more to come before the project is completed.

1) Damion Searls’ translations

A selection of these are included in the book, but there are many more and I hope it will be possible to find a way of bringing out a wider selection from his essays, journalism and letters in due course.

2) A film with Shona Illingworth

![Shona Illingworth at Cap Arkona]()

I began discussing the investigation with the artist and film-maker Shona Illingworth after talking about it at the “Shorelines” weekend curated by Rachel Lichtenstein, and held in the Tilbury Cruise Terminal as part of Metal’s Estuary festival on 17 & 18 September 2016. She was interested in the value Johnson placed on often degraded “backwater” communities and landscapes, in his interest in memory, and also in the unexpected things he glimpsed in the sea view over the outer reaches of the Thames estuary from his window at Sheerness. I delivered a similar talk shortly afterwards at Shona’s conference “Invisible Architectures: Lesions in the Landscape,” at the Whitechapel Gallery in London, 30 October 2016. We continued to discuss the widely scattered geographies that were gathered into Johnson’s Kentish sea view, and also his way of carrying the traumatic history he had lived through. We talked a lot about the wreck of the SS Richard Montgomery, a still bomb-filled American Liberty Ship poking out of the water outside his window in Sheerness. Johnson described this menacing thing as the town’s true “memorial” to the Second World War —and, as in the book, we considered it in the light of his scarifying earlier description, in Anniversaries, of the RAF’s devastating destruction of the SS Cap Arcona in the German Baltic.

Our conversation has become a collaboration and we have been working towards a film since 2017, visiting Mecklenburg and West Pomerania, and also, of course, the Isle of Sheppey. The “filmlets” used on this site are drawn from Shona’s research footage. With the help of the curator Sue Jones, who is artistic director of the Whitstable Biennale and also of the umbrella organisation Cement Fields, we made a conversational “sound work”connected (but by no means confined) to the book. This which was broadcast on Sheppey Community Radio as part of the second Estuary Festival in June 2021 and is available at the too left page of this website’s home page. We intend to conclude the investigation with a Hanseatic film in 2022.