The Sea View

Has

Me Again:

Uwe Johnson in Sheerness

About the project and its outcomes

I first came across the writings of Uwe Johnson as a student at the University of Kent at Canterbury in the early 1970s. At that time, Jonathan Cape and Penguin were offering British editions of American translations, so we had access to the three novels on which Johnson’s reputation rested in West Germany — Speculations about Jakob (1959), The Third Book about Achim (1961), Two Views (1965) — and also the novella entitled An Absence, which I bought as published in Nathaniel Tarn’s mind-opening series of Cape Editions in 1969. I didn’t read all these books at the time, but I did take in enough to understand that Johnson was a truly exceptional writer, whose formally innovative works explored the post-war division in which both ideologically polarised German states shared the same guilty past. He was a political writer, to be sure, but no side’s partisan hack. As Jean Baudrillard had written in 1962, Johnson wrote as “an artisan of language” rather than a “manager of conscience.” Reluctant to be called an “artist”, he thought of himself as a storyteller who used fiction to get at the truth of situations. Even the design of his book plate identified him with “making” rather than lofty inspiration: it showed various different patterns of brickwork used on traditional buildings in Northern Germany.

Years later, I discovered that, in 1974, this restless and remarkable author, who had refused to shake down on either side of the Cold War division (he once declared himself on the left “but in a different spot”), had moved with his wife and daughter to Kent. Far from choosing a place that might confirm the cliché claiming this southern English county as “the Garden of England”, he opted for Sheerness, an isolated and apparently busted ex-naval town on the marshy and often windswept Isle of Sheppey, where the no longer naval river Medway flows out into the last stretch of the Thames estuary.

For years after his chaotic death there in February 1984, I assumed the story of Johnson’s English decade would one day be told by a properly qualified scholar of modern German literature. Yet no such person seemed to come along. My interest was sharpened when I realised that Johnson had actually written quite a lot about his experiences on the Isle of Sheppey. This was revealed by the appearance in Germany of a book entitled Inselgeschichten (Island Stories). Edited by Eberhard Fahlke and published by Suhrkamp in 1995, the volume contained articles, essays and more or less fragmentary extracts from letters that Johnson had sent from Sheerness to friends and acquaintances including Max Frisch, Helen Wolff, Walter Kempowski and Christa Wolf. Who could resist the discovery that Johnson had once written to the philosopher Hannah Arendt in New York, inviting her to sit with him and enjoy the sea view from the promenade at Sheerness?

I returned to the matter again in 1999, when making The River, a series of television documentaries about the Thames. Nothing positive, however, came back from the British publishers I sounded out about the possibility of commissioning an edited translation of Island Stories. The objection, which I would later hear repeated about the book I did eventually write, ran along the same lines (even when it was conveyed in silence). I was told that nobody in Britain knew or, almost certainly, cared who Uwe Johnson was. His life and death in Sheerness sounded utterly miserable. As for the Isle of Sheppey, well why would anyone want to read about a notoriously desolate place like that?

Such forebodings have encouraged me to ask myself what bearing this investigation might really have on our time with its transformed technologies, its globalised neoliberal economics, it’s defensive insularity and it’s populism. What is it about Johnson and his work that is really worth knowing to English-language readers nearly four decades after his death? And could it be convincingly claimed that the Isle of Sheppey, which had been so direly afflicted by the closure in 1960 of the Admiralty dockyard and associated naval command and army garrison at Sheerness, was more than just a deindustrialised and “left behind” backwater with nothing useful to tell anyone? Was it really conceivable that the closure had actually turned the island into an accidental testbed where the future we are living in now was already being incubated forty or fifty years ago? As for Johnson, this awkward East German Crusoe perched on the observatory he made of his bar stool in the Napier Tavern, was he actually a prescient witness rather than a blown-in and at least half-distressed foreigner, registering and also describing what happened to people when the wave of post-war social democracy finally broke and the discontents that would eventually come to a head in the Brexit referendum of June 2016 began to emerge?

It was not until I was appointed to a full-time job (my first since 1987) at King’s College London, that it finally became possible for me to find the time and resources to pursue the investigation properly. Soon after joining King’s in September 2011, I contacted Johnson’s publisher, Suhrkamp Verlag, and asked if might be possible to commission an English translation of the pieces gathered in Island Stories. They were helpful and put me in touch with the brilliant American translator, Damion Searls. He had long since made and described his own fleeting visit to Sheerness. He had also brought Johnson’s A Trip to Klagenfurt into English, and was then preparing to embark on the first full English translation of Anniversaries: From a Year in the Life of Gesine Cresspahl, a massive and, by now, award-winning undertaking which was finally published by New York Review Books in 2018. Damion was enthusiastic, so I applied to the Patsy Wood Trust, set up to make constructive use of the estate of my late cousin (an environmentalist whose parents had invented magnetic resonance scanning in a garden shed that was the beginning of Oxford Instruments). The trustees kindly provided a grant for the cost of some preliminary research as well as the translations.

There were, of course, libraries and archives to visit. There were also conversations without which I could not have proceeded: with Damion Searls, to be sure, and also with Holger Helbig and others connected to the Uwe Johnson Society and the Uwe Johnson Archive at the University of Rostock. There were diverse watery landscapes to visit and revisit too: some on the Isle of Sheppey, of course, but I also had to familiarise myself with some of the rivers, coastal spits and “backwaters” that Johnson had in mind from earlier years. I had to breathe the air of some of these places in order to grasp Johnson’s comparative and trans-national way of thinking, in which views and landscapes became bearers of memory as well as history. So I visited Mecklenburg and West Pomerania, and also New York City, where Staten Island had joined Johnson’s repertoire of evocative places.

One of the first talks I gave about my ongoing investigations took place at Aldeburgh, as part of Gareth Evans’ weekend “Place: Roots – Journeying Home”, held at the beginning of February 2013. Soon after that I started planning a 45 minute radio documentary with John Goudie, a BBC producer with whom I had worked before (on previous assignments we had stayed in a roofless house on the Hebridean island of Eigg and also in a windy Depression era hotel in Marfa, West Texas, so Sheppey was easy). Commissioned by BBC Radio Three, and made with the help of a German-speaking researcher, Helen Whittle, “A Secret Life: Uwe Johnson in Sheerness” was first transmitted as a 45 minute “Sunday Feature” on 19 April 2015. The programme, which is still available on BBC Sounds and also on other podcast sites (including Apple), attracted various interested comments after transmission. Some of the most helpful came from people who had lived in Sheerness in the seventies and got in touch to offer observations and recollections that added to what we already knew.

How though, does an outsider make meaningful contact with the residents of a town that is all too familiar with the derision of mainlanders convinced that “Sheermess” is an abandoned and dismal place on an island occupied by inbred “Swampies” with webbed feet and only two fingers on each hand? Having started out in the public library and The Belle and Lion, a new and popular Wetherspoon pub a little further along the High Street, I was pleased also to meet up with the conservationist Will Palin, who was already working towards the restoration and return to community use, of the derelict Dock Church across the moat between the town and the port that was once Sheerness dockyard. He provided me with a place to stay and also put me in touch with Chris Reed of The Big Fish, a community arts organisation in Sheerness.

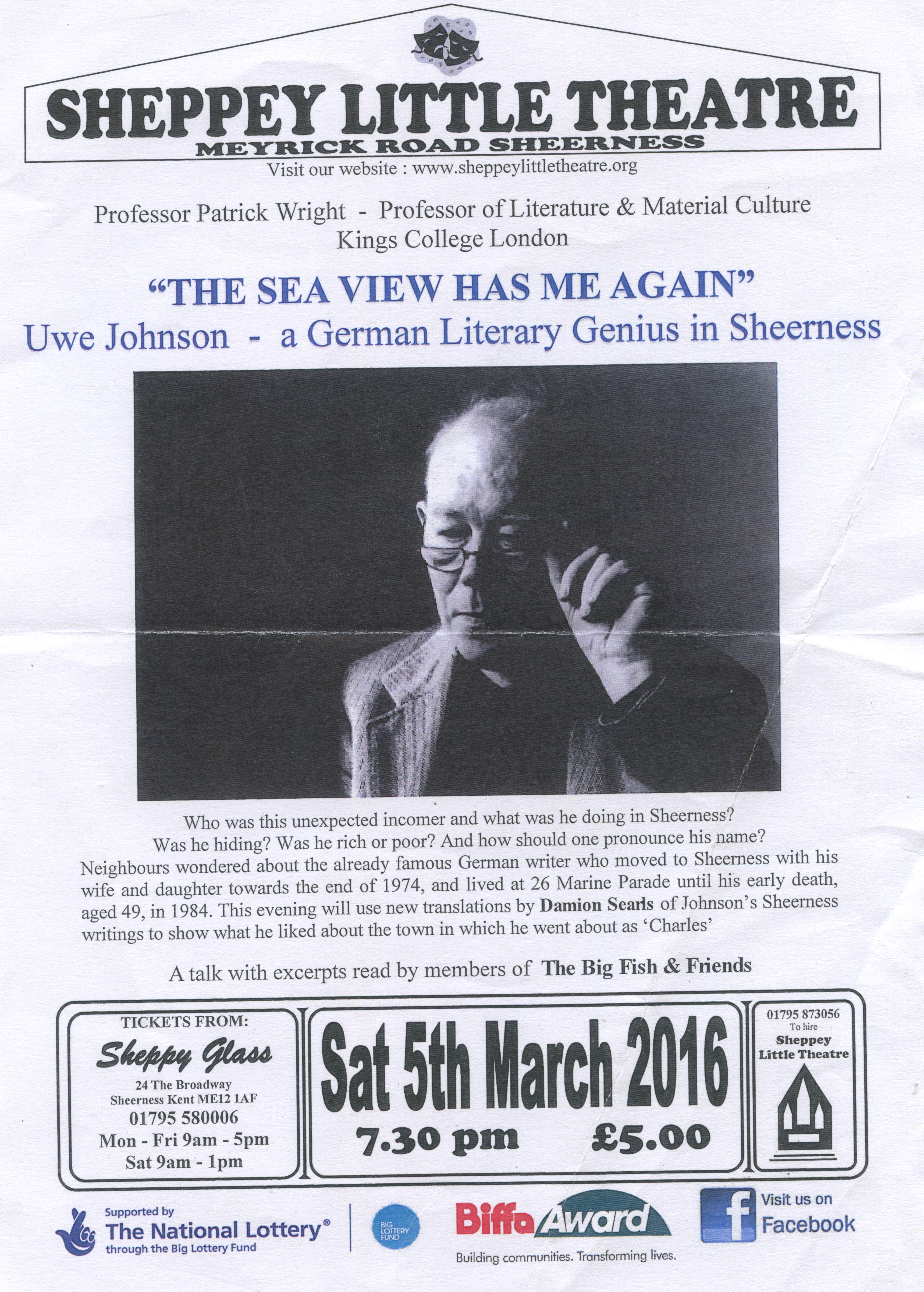

Reckoning that very few people on the island had much idea about the German writer who had lived in their town for nearly a decade, Reed and I decided to use some of Damion’s translations to change that. Having sent out the call for interested people — the group became “The Big Fish and Friends” — we initiated a series of meetings for which we squeezed into the Rose Street Cottage of Curiosities just off Sheerness High Street. Commenced towards the end of 2015, our assemblies became more like rehearsals as the winter proceeded. The outcome was an evening of readings presented together with a talk by myself, on Saturday 5 March 2016 at the Little Theatre in Meyrick Road, Sheerness. Some of our selected fragments remained as read texts. Others, including those in which Johnson had captured conversations in his favourite bars (the Napier Tavern and, in the earlier years, the since demolished Sea View Hotel), had become semi-staged performances with various props, including a bar of sorts and Johnson’s own stool, which successive licensees at the Napier Arms have been careful to preserve as a relic.I remember being told that 54 people bought tickets and pride was duly taken in the fact that this was rather more than had paid up for a Del Shannon tribute band a week or two earlier.

![Big Fish and Friends at Sheppey Little Theatre, 5 March 2016]()

![Caption: Big Fish and Friends at Sheppey Little Theatre, 5 March 2016]()

![Caption: Big Fish and Friends at Sheppey Little Theatre, 5 March 2016]()

![Caption: Big Fish and Friends at Sheppey Little Theatre, 5 March 2016]()

![Caption: Big Fish and Friends at Sheppey Little Theatre, 5 March 2016]()

![Caption: Big Fish and Friends at Sheppey Little Theatre, 5 March 2016]()

![Caption: Big Fish and Friends at Sheppey Little Theatre, 5 March 2016]()

![Caption: Big Fish and Friends at Sheppey Little Theatre, 5 March 2016]()

![Caption: Big Fish and Friends at Sheppey Little Theatre, 5 March 2016]()

The Big Fish and Friends assembled again not long afterwards, this time at the Napier Tavern, to record versions of the texts for Daniel Nash, who broadcast them on Daniel’s Monday Night Community Show on “the island’s very own truly local radio station” BRFM (“Best Radio for Miles”). This was followed by a repeat performance, not at the Little Theatre this time, but on board LV21, once the Goodwin Sands lightship but now a floating venue, which was moored at Gravesend as part of Metal’s 2016 Estuary festival.

![Jim Enright and Chris Reed of The Big Fish and Friends]()

Having learned a lot from these conversations, and others that they made possible, I concentrated on researching and writing the book that shares its title with those events involving The Big Fish and Friends. I was greatly assisted by the award of a Leverhulme Fellowship in 2015, which gave me a year in which I didn’t have to think about anything else. I must admit also to having benefitted from the first Covid-19 lockdown, which made it unusually easy to concentrate on pulling the final book together.

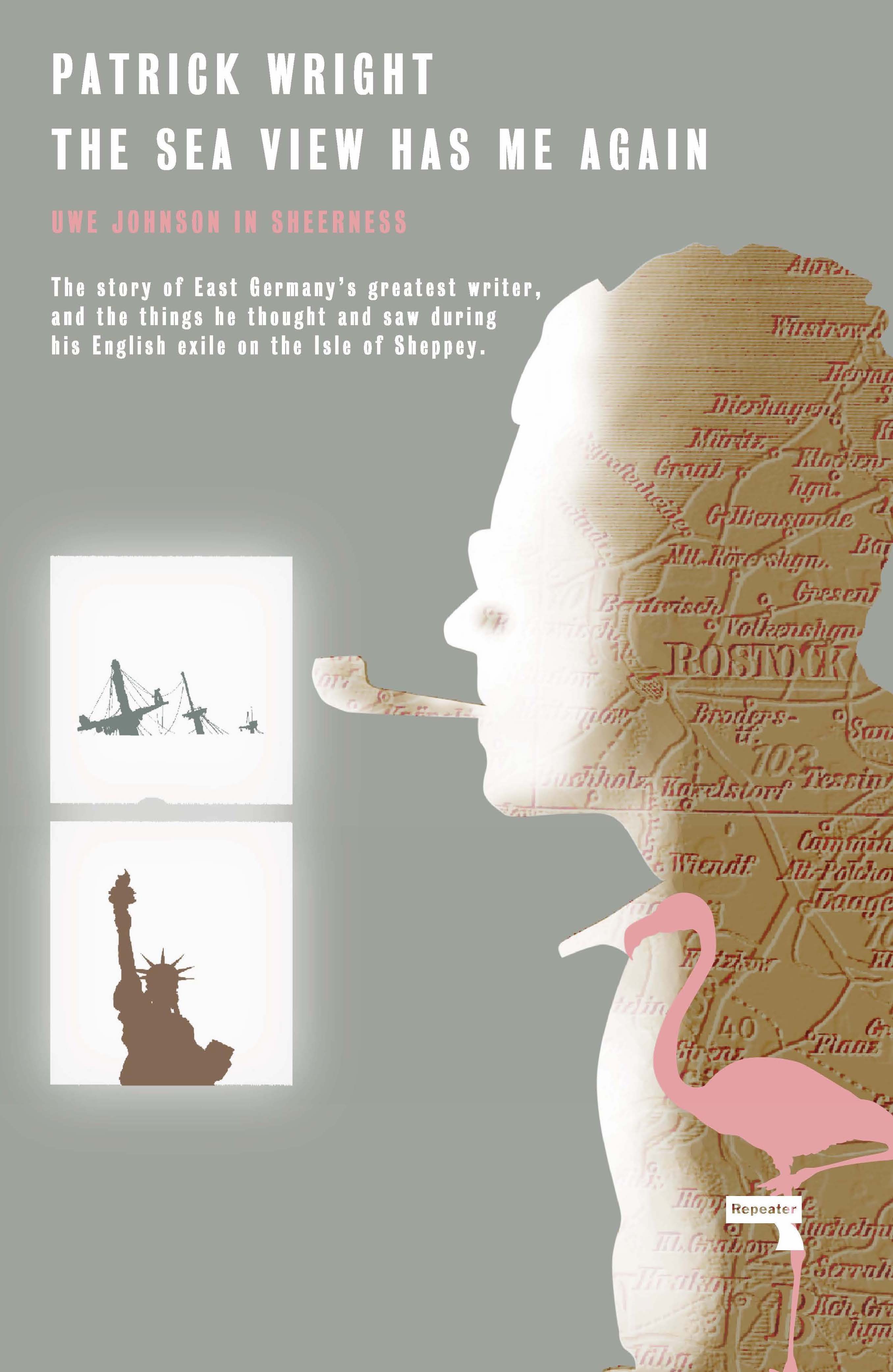

Finished in August 2020, The Sea View Has Me Again: Uwe Johnson in Sheerness, was published by Repeater Books on 8 December 2020.

There is more to come before the project is completed.

1) Damion Searls’ translations

A selection of these are included in the book, but there are many more and I hope it will be possible to find a way of bringing out a wider selection from his essays, journalism and letters in due course.

2) A film with Shona Illingworth

![Shona Illingworth at Cap Arkona]()

I began discussing the investigation with the artist and film-maker Shona Illingworth after talking about it at the “Shorelines” weekend curated by Rachel Lichtenstein, and held in the Tilbury Cruise Terminal as part of Metal’s Estuary festival on 17 & 18 September 2016. She was interested in the value Johnson placed on often degraded “backwater” communities and landscapes, in his interest in memory, and also in the unexpected things he glimpsed in the sea view over the outer reaches of the Thames estuary from his window at Sheerness. I delivered a similar talk shortly afterwards at Shona’s conference “Invisible Architectures: Lesions in the Landscape,” at the Whitechapel Gallery in London, 30 October 2016. We continued to discuss the widely scattered geographies that were gathered into Johnson’s Kentish sea view, and also his way of carrying the traumatic history he had lived through. We talked a lot about the wreck of the SS Richard Montgomery, a still bomb-filled American Liberty Ship poking out of the water outside his window in Sheerness. Johnson described this menacing thing as the town’s true “memorial” to the Second World War —and, as in the book, we considered it in the light of his scarifying earlier description, in Anniversaries, of the RAF’s devastating destruction of the SS Cap Arcona in the German Baltic.

Our conversation has become a collaboration and we have been working towards a film since 2017, visiting Mecklenburg and West Pomerania, and also, of course, the Isle of Sheppey. The “filmlets” used on this site are drawn from Shona’s research footage. With the help of the curator Sue Jones, who is artistic director of the Whitstable Biennale and also of the umbrella organisation Cement Fields, we made a conversational “sound work”connected (but by no means confined) to the book. This which was broadcast on Sheppey Community Radio as part of the second Estuary Festival in June 2021 and is available at the too left page of this website’s home page. We intend to conclude the investigation with a Hanseatic film in 2022.

Uwe Johnson in Sheerness

by Patrick Wright

with extracts from Uwe Johnson’s Island Stories

translated by Damion Searls

London: Repeater Books, Hardback,

8 December 2020. ISBN: 9781912248759

Paperback, June 2021

See at the publisher’s site, at UKBookshop.org

Towards the end of 1974, a stranger arrived in the small town of Sheerness on the Isle of Sheppey in Kent. He could often be found sitting at the bar in the Napier Tavern, drinking lager and smoking Gauloises while flicking through the pages of the Kent Evening Post. “Charles” was the name he offered to his new acquaintances.

But this unexpected immigrant was actually Uwe Johnson, originally from the Baltic province of Mecklenburg in the GDR, and already famous as the leading author of a divided Germany. What caused him to abandon West Berlin and spend the last nine years of his life in Sheerness, where he eventually completed his great New York novel Anniversaries: From a Year in the Life of Gesine Cresspahl in a house overlooking the outer reaches of the Thames Estuary? And what did he mean by detecting a “moral utopia” in a town that others, including his concerned friends, saw only as a busted slum on an island abandoned to “deindustrialisation” and a stranded Liberty ship full of unexploded bombs?

Patrick Wright, who himself abandoned north Kent for Canada a few months before Johnson arrived, returns to the “island that is all the world” to uncover the story of the East German author’s English decade, and to understand why his closely observed Kentish writings continue to speak with such clairvoyance in the age of Brexit. Guided in his encounters and researches by clues left by Johnson in his own “island stories”, the book is set in the 1970s, when North Sea oil and joining the European Economic Community seemed the last hope for bankrupt Britain. It opens out to provide an alternative version of modern British history: a history for the present, told through the rich and haunted landscapes of an often spurned downriver mudbank, with a brilliant German answer to Robinson Crusoe as its primary witness.

The Preface

as republished on Literary Hub

Launch Conversations

USA: A conversation, with Edwin Frank, Editorial Director of New York Review Classics and translator Damion Searls, via the Community Bookstore, Brooklyn, 5 January 2021. See on YouTube

UK: “Where Might We Find a Moral Utopia?” Bristol Festival of Ideas, Tuesday 16 February 2021

Available here

“Beyond the Sea: Uwe Johnson, Patrick Wright and the Isle of Sheppey”, a conversation with Simon Matthews, the Quietus, 27 February 2021.

![Blue Town Heritage Centre, set for a wedding tea]()

Previews

“This tidal book, reaching into everything and then withdrawing to show what it left behind, is a triumph.”

— Neal Ascherson, author of Black Sea and The Death of the Fronsac

“A double ‘biography’ of the great but always tempestuous German writer Uwe Johnson and his ultimate home, the gritty and disreputable Isle of Sheppey. ‘Biography’ is in quotes because Wright is a saboteur of genres and his books encompass multiple worlds. I stand in awe of what he has accomplished here”.

— Mike Davis, author of City of Quartz and Set the Night on Fire

“Patrick Wright has written an extraordinary, haunting book, a devastating allegory of our own time, yet seen from the mid-twentieth century. Wright’s phenomenal achievement is to painstakingly set the scene against which the final volume of Uwe Johnson’s monumental four-part novel Anniversaries can be read and to turn it back to us, with a contemporary question — are we left behind or staying behind?”

— Gillian Darley, author of Villages of Vision and Excellent Essex

“An astonishing chronicle of the great German author Uwe Johnson, who moved to Sheerness, Kent in the 1970s.”

— Helen MacDonald, author of His for Hawk and Vesper Flights

“With consummate timing, when so many are locked in a blind charge towards some bigger and better crisis, Patrick Wright has picked over the landfill of a very specific Estuary culture to devastating effect. The Sea View Has Me Again is a monumental sifting and arranging of local particulars, stitched against the savage farce of a great European novelist’s elective exile. Remorseless retrievals from bunker and cranked microfilm, enlivened by human witness, make this final panel of a notable literary triptych, following on from A Journey through Ruins (Dalston Lane) and The Village that Died for England (Tyneham), into one of the abiding memorials to a tattered angel of history”.

— Iain Sinclair, author of Downriver and The Last London

“In this masterful modernist history, Patrick Wright tells the story of an island which is England, yet much more than that. Wright’s Isle of Sheppey is a de-industrialised place, not in the North, but in the garden of England; a refuge of liberties that has three prisons; a dockyard and garrison town with a pacifist MP; an island which could be destroyed by bombs left over from the war, but which far from being stuck in the past is a model for a new post-industrial world. It is the stage for an extraordinary cast of characters, among them Napoleon Bonaparte, DH Lawrence’s mother and an Anglo-Catholic fascist parish priest; the Wright brothers’ patent agent, the nation’s first indigenous aviator and the father of the British atomic bomb; the communist leader of the engineering union, an immigrant imperialist machine-tool inventor; makers of modern furniture and foreign photographers.

At its heart is the life, work, and inspiration of extraordinary East German writer Uwe Johnson who drinks himself to death in a pub run by veterans of the Battle of the River Plate. Wright scintillatingly creates, from perfectly observed fragments from the past and flashes of a better future, a British history like no other, crafted with tools forged out of hard realities of modern European history. With its steely dissing of the tide dichotomies and exceptionalist clichés which disfigure our sense of who we are, this is Patrick Wright’s most important book. It brings Europe to England by showing it has always been here, at a moment when too many want to believe something else.”

— David Edgerton, author of The Rise and Fall of the British Nation and The Shock of the Old

Reviews

“A model portrait of person and place, a kind of cultural and literary geography that never fails to fascinate.”

— KIRKUS (starred review)

“Sebald on steroids… I loved every scrap of it”

— John Mitchinson, BACKLISTED

“Beautifully written, defiantly oddball, challenging in so many ways and completely compelling.”

— John Wyver, Illuminations Media

“... a huge achievement: a comprehensive portrait of a place and a person, and the best book about Brexit that’s yet been written.”

—Jon Day, “Books of the Year”, The White Review

“The first telling of a life tends to be heroic, dramatic, and efficient. But a second telling can always be imagined, built of stories left out of the first for any number of reasons. This second, inverse telling might be arduous, indirect, speculative, and sad. It might provoke a reaction of what-exactly-is-this?, like Rachel Whiteread’s negative-space sculptures of building interiors. It might also be as valuable as the first.”

—Ben Ratliff, review at 4columns.

“Sometimes the most necessary books turn out to be the ones you didn’t realise you needed. Before reading Patrick Wright’s The Sea View Has Me Again (Repeater) I had no idea that there was a hole in my life waiting to be filled by a 750-page book about an East German writer and his ten-year self-imposed exile on the Isle of Sheppey during the 1970s. But I was entirely captivated by this microscopic, discursive study of Uwe Johnson, a pioneering novelist who crossed the Iron Curtain but declined to fall at the feet of the capitalist West, opting finally to settle himself and his family in Sheerness, apparently on the basis that it was the closest thing he could find to East Germany without the Stasi. It is also a great book about the relationship between Britain and the rest of Europe, and not a page too long.”

—“Books of the Year,” New Statesman, 17 November 2021

“I am increasingly obsessed with place as a way to understand history and the techtonic shifts in culture and society. Very few pieces of writing have matched Patrick Wright’s new book in the ability to chart, through one place and one life, the startling shifts of the past half century. On the face of it this is a book about Uwe Johnson (the under-read and perhaps under-appreciated German writer) and his life in Sheerness on the Kentish Isle of Sheppey. But, as with all of Wright’s work over the decades, it is so much more: a study of deindustrialisation and decline, a history of England and of the Kent coast, and a stunning work of both biography and literary criticism.”

—Verso, Staff Picks 2020

“If you are looking for a straight biography, then keep browsing. If, however, you are after an eccentric, brilliant, digressive, idiosyncratic, social-historical door stopper to get lost in, then Patrick Wright has produced something special. Wright uses psychogeography and psychobiography to bleed the life of Johnson through the veins of Sheerness, thus giving life to the town. In a sprawling narrative that layers the kernel of Johnson’s life, he also creates a beguiling memento mori to a place that has often been left for dead by central authorities, and a German writer who moved there from New York with (at worst) something of a death wish, or (at best) with the overwhelming burden of finishing his magnum opus Anniversaries. A best book of 2020 contender.”

—NJ McGarrigle, Irish Times.”

—Zinovy Zinic, Books of the Year, TLS, 2021

“Clearly, as Patrick Wright suggests in The Sea View Has Me Again, Charles found the ‘deadpan catastrophic tone’ of Thames Estuary banter congenial, or just familiar. But then, from the Baltic shores to Staten Island, Charles was a haunter of those places where “truth and dischevelment run together in not always melancholic ways that repay reflection’... Wright plays both the anatomist and the elegist for the blighted modernity of seemingly forsaken spots such as Sheppey. Here, grand designs — for post-industrial prosperity after its naval dockyards closed in 1960, or for a Kentish dolce far niente in ‘seaside Bohemia’ — stalled in a state of “perplexing oscillation in which paradise kept collapsing into the bleakest kind of slum’... As it emerges, Wright’s fresco becomes a fragmentary panorama of traumatic, half-remembered history, personal and national. He tells an often sad story, about an island seemingly in stasis and Johnson’s descent into “illness, drink and paranoia” — but one tidally washed in the dry wit so enjoyed by Charles’s bar company.”

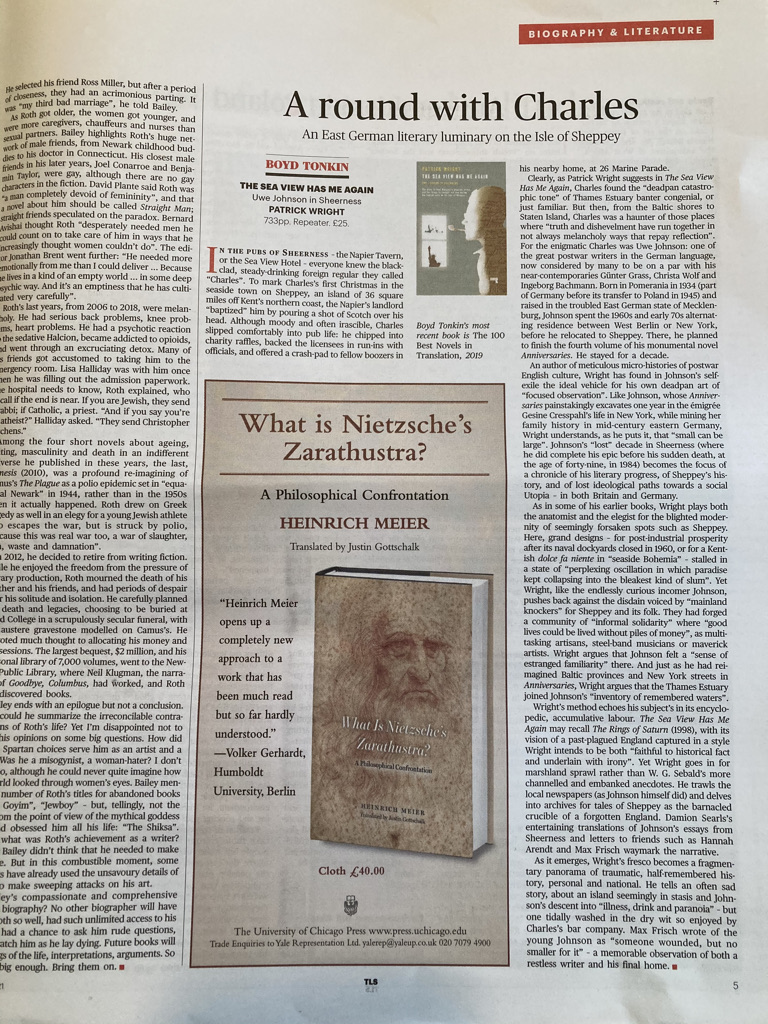

— “A round with Charles,” Boyd Tonkin, Times Literary Supplement

![]()

“A hymn to estuarial peculiarity and a lament for an awkward man determined never to find his place.”

—Jonathan Meades, The Literary Review

“Reading Wright’s magnificent account we sympathize with Johnson’s plight. We

might even see the exiled German as a spiritual brother to Marvin Gaye

remembering that the singer (in an oddly similarly move) hid out in Ostend,

another backwater on the opposite North Sea shore. Both of them owlishly

looked out at the world and asked plaintively – what’s going on?”

—John Quin, The Common Breath

“. . . a glorious rabbit hole of a book. It is a longue durée portrait, from the 17th century to Thatcher, of a single location on the edges of British national life. It is also one of the most immersive evocations of the 1970s I know, fine-grained in its particularity and yet also alert to the general conditions whereby, in places like Sheerness across the postindustrial West, the midcentury economic miracle lay sedated, awaiting its death.”

Nicholas Dames, Public Books, Public Picks 2021,

“The book also doubles as one of the best-researched texts about the Island. It deals with its legends, such as Grey Dolphin; the prison hulks of Dickens; the mysteries of Dead Man's Island and Sheppey's run-in with the Dutch when Queenborough was captured by invading forces in 1667.

It includes Island characters like showbusiness entrepreneur Stan Northover who ran the Island Nightclub at Leysdown and "celebrity clairvoyant" Mia Dolan; celebrity visitors; and a painstakingly detailed account of the magnificent men in their flying machines, like Charles Rolls, who pioneered British aviation from the fields of Shellness and Eastchurch.

It also reminds readers how successive governments have left Sheppey to hang out to dry with illustrations of failed industries including the ill-fated Murad car which was years ahead of its time but ran out of road when a promised relocation loan to the Island was removed by the Board of Trade.

Mr Wright has left no stone unturned in his quest to unearth the strange allure of Sheppey and its people.”

— John Nurden, Sheerness Times Guardian

“This book is about many things: the rise of post-industrial society in Britain in the 1970s and 1980s; the ways that diverse memories and feelings can be melded into a narrative by an author to give them some kind of shape and explanatory power; the relationship between location and imagination. Finally it is testament to the ways in which writing offers a sort of salvation, even to the most blighted of souls.”

— Kerry Brown, “Uwe Johnson: The Enigma of Sheerness-on-Sea.”

“Wright’s book also rests on the subtle shaping of small-scale materials over a large expanse. The last hundred pages are particularly powerful, a final movement which begins quietly enough by introducing the note of the fabulous with the old German story of ‘The Fisherman and his Wife’.

The husband is granted wishes which his wife persuades him to inflate−to live like a prince, a king, an emperor, a pope − until she demands to live like God, and they are left again with their filthy shack. The typicallambiguous ending − have they in fact been granted their wish? Is this in fact how God lives, given the nature of the world? −leads to another marine tale, almost equally fabulous, about equally unmanageable gifts.

The SS Richard Montgomery, an American Liberty ship, sank in sight of Sheerness in 1944 with all its cargo of unexploded bombs and its masts still remain visible above the waves and its lower decks are still packed with chemicals which, as inhabitants claim and Johnson will have heard, produce fantastic lights that dance over the rigging at night.

This sets Wright in place to tell his final marine tale, after confirming that the lie of land and sea at Sheerness does indeed make the view akin to that over the Baltic from the Bay of Lübeck. This is a tale of May 1945 and the Nazis in retreat, of herding thousands of concentration camp inmates onto the Cap Arcona and Thielbeck with the intention of scuttling the ships off Lübeck, only to be beaten to the destruction by British bombers intent on denying crucial shipping to the retreating Germans, and of the roughly 8000 bodies that afterwards floated in wave after wave to the shores, where − to bring the cycle of ambiguous tales circling back, like the sweeping gaze of a watcher on the shore − the child Gesine Cresspahl finds them crowding in, as she describes in the final days of Jahrestage.

If we can no longer look directly at that opening metaphor of waves

sweeping in, ‘hunchbacked with cords of muscle’, or fail to see what is exactly literal about the final identification at the close of the fourth

volume, of walking into the sea with being on the way to the place where the dead are, Wright’s tour de force will have brought us quietly and surely back to Johnson, gaining for its seemingly eccentric enterprise a full and complete justification.’

—Max de Gaynesford, London Magazine.

‘The Isle of Sheppey which Johnson arrived in with his wife and daughter was not so different from the one Wright found forty years later: deep in cultural, economic and infrastructural neglect; prone to flooding and erosion; disparaged for its poverty, its marginality and the supposed parochialism of its inhabitants. A place of cheap holidays, ‘white flight’, potholed roads, prefabs and bungalettes, it was a stereotype of terminal England and insular Englishness: an island’s island. This one-time seaside resort, shunted aside by cheap air travel, abandoned by industry, its naval dockyard closed, tells us something about the country we live in now. It’s a place where the prefix ‘post-’ roams vampirically, looking for things to attach itself to. Wright extrapolates a history of England now, a country where the 1970s and 1980s never went away. . .

Once the reader grasps what these books [Anniversaries and The Sea View Has Me Again] are doing, they appear as masterpieces of compression and connectivity, feats of documentary imagination that have no equivalents even in the places we might expect to find them: modernist novels, Annales histories, psychogeographical adventures...’

—Patrick McGuinness, London Review of Books.

Preliminary and Associated Texts and Transmissions

“The Sea View Has Me Again” - a sound work by Patrick Wright and Shona Illingworth, Estuary Festival (first broadcast on 23 May 2021)

“The Piano Man, no ordinary scrounger,” posted on Various Small Fires 17 April 2015 (first outing of a text that has not yet been published in its final form - except at the top of the left front page here.)

“The Moral of Brenley Corner,” London Review of Books 6 December 2018.

“Turning Inward: Brexit, Encroachment Narratives and the English as a ‘Secret People.” Presented at the British Academy, 4 November 2016 and published in Ash Amin & Philip Lewis (eds.), European Union and Disunion: Reflections on European Identity, London: British Academy, 2017, pp. 64-72

“”