England’s Last Acceptable Asylum Seeker?

The Lesson of the Piano Man

by

Patrick Wright

(posted 26 May 2021)

As you drive east, Marine Parade seems to leave

Sheerness at two different speeds. To the left the sea wall closes in on the road abruptly,

having at first wandered off to secure a no longer so dishevelled Georgian house that

was once the combined home and HQ of Mr. D. T. Alston, king of the 19th

century Kentish oyster trade. To the right the town thins more

gradually, extending through a line of houses, a pub named ‘The Ship on Shore’, and a

chalet park before yielding to a stretch of watery marshland on which malaria-bearing anopheles mosquitoes were still worrying the responsible medical officer in the 1940s. The junction with The

Leas is overlooked by a solitary building known as The White House. Since 2008, this has been an Indian restaurant. At the time of the events described here, it was still battling on in its traditional role as a pub.

Being on the

northern shore of the Isle of Sheppey, at the mouth of the Thames estuary where

the London river finally flows out into the North Sea, the shingle beach at

Scrapsgate has long been known for its distinctive harvest of washed-up objects. On 19 June 1756, the Oxford Journal reported that ‘A monfstros

Fifh, fuppofed to

be a young Whale, is come afhore . . . It meafures thirty fix Feet and a half

in Length, twenty-two Feet in Circumference, and eight Feet from the Eyes to

the Tip of the Nofe.’

If whales can founder here so too can ships, hundreds

of which have run aground on this coast, including, in 1848, a vessel named the

Lucky Escape, which carried a cargo of barrels.

The ship was salvaged—the Kentish word for this semi-piratical activity was “hovelling”—by islanders who had good reason to be optimistic about their

find. Two years previously, a revenue

cruiser named the Vigilant had boarded a vessel seen acting suspiciously

offshore a mile or two from here and, having dragged the water beneath her,

recovered 122 barrels of ‘contraband

spirits’ roped together and sunk for later recovery.[i] The barrels on the Lucky Escape, however, turned out to be filled with Portland

cement, a material that was then manufactured on the southern shore of the

island and transported upriver to supply Victorian London’s building booms. They were only

good for ornamenting the distinctive ‘grotto’ (now one of Sheppey’s Grade II listed

buildings), which to this day adorns the

car park of another pub—opportunely renamed the ‘Ship on Shore’—across the

road.

![]()

Smaller but still

noteworthy objects have turned up in these waters too. In June 1893, a diver from the Admiralty

dockyard at Sheerness picked up a bottle floating in the sea: inside he found an undated message reading only ‘Lost off the Goodwin Sands. Please tell my wife A. Chamberlain,

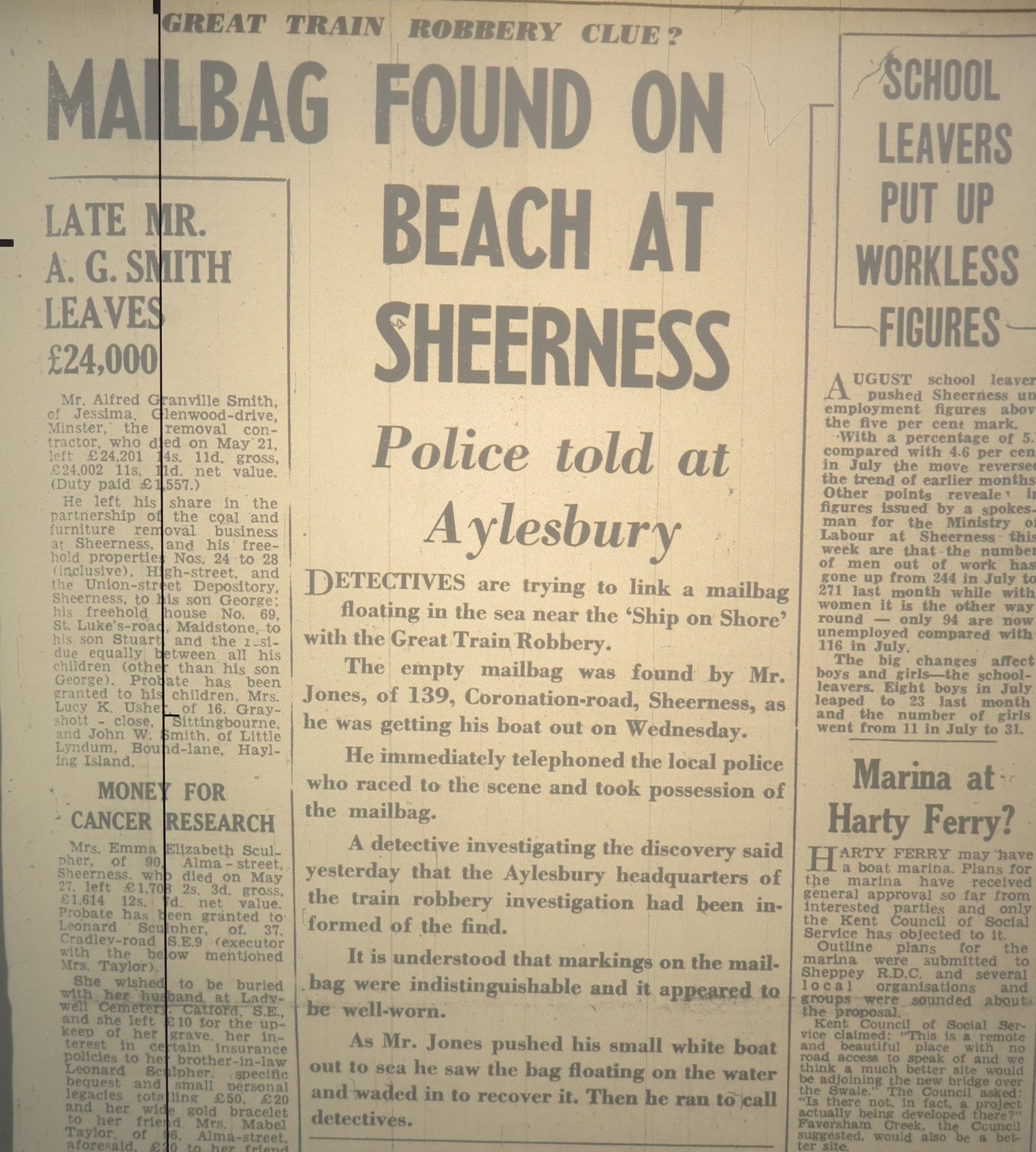

Lavender-hill, Enfield.’[ii] On September 4th 1963, Mr. Jones

of 139 Coronation Road, Sheerness, was getting out of his boat near the ‘Ship

on Shore’ when he noticed a mail bag drifting in the sea. He immediately telephoned the Sheerness police

who ‘raced to the scene and took possession’ of it. Although inspection

revealed the bag to be so ‘well-worn’ that the markings on it were

indistinguishable, the excited police still alerted their colleagues in

Aylesbury, Buckinghamshire, on the hunch that their find might be connected to

the sensational Great Train Robbery of the previous month. [iii]

![]()

Human bodies have also been found on this disconcertingly productive shore: drowned sailors and fishermen, and others who have made

the same decision as Thomas Kirkham, a 40-year old private in the Royal Marines

who put an end to his troubles here on Tuesday 15 January 1878. He had, as his wife would inform the coroner at

an inquest held at The Ship-on-Shore, been ‘rather fond of drink lately’ and had

probably also gone ‘absent’ from his military duties.[iv] The

landlord told the coroner that Kirkham had been in ‘the

grotto’ by 7.20 that morning. He was

later seen wandering about on the beach, ‘apparently without any object’. The following

evening a boatman with the coastguard service came across his corpse, washed up

by the sandheap on which he had early been pacing aimlessly. ‘Found

drowned’ was the verdict in this case as in others before and since. That couldn’t be said of the corpse some

local boys found floating here in August 1976.

Wrapped in brown paper and placed in a green canvas bag tied with

“ordinary parcel string”: it was probably, so the police declared after announcing

that ‘foul play has been ruled out,” the embalmed corpse of a woman who had

been incompetently buried at sea about three years earlier.

From Local Story to Global Legend

There was nothing

dead about the young man who was spotted by residents looking washed up and confused on the beach opposite the White House. The sighting was duly reported to the police, and the man was picked up in

the early hours of April 7, 2005 by two officers who had found him behaving strangely in Sheerness. Both agitated and speechless, he had nothing on him to reveal his name

or identity. There had been heavy rain

that night, but the arresting officers noted in their log that the stranger,

who was soaking wet and shivering, did indeed appear to have been in the sea.

A month or so

later, the first newspaper report about this discovery appeared in the Sheerness Times Guardian. Headed ‘Piano clue in bid to identify

hospital patient’, it was a small item, printed at the top of page 7 on May 5,

2005, which happens also to have been the day of the general election in which

Tony Blair won his third term of government for the Labour Party.

“Do you know

this man?” asked this local weekly of its readers, before explaining how he had

been taken by the police to the Medway Maritime Hospital in Gillingham, across

the Swale on the mainland, where he was now being ‘cared for by NHS and Social

Services staff.’ The paper reported that

the man, who had remained mute since being found, appeared to be between 20 and

30 years old, and “approximately 6 ft tall with what looks like either dyed

blonde hair or unusually greying hair and light brown eyes.” It added that “When he was found he was

wearing a black suit, black tie and white shirt.” According to a spokesman from the hospital, “the

only other clue is that he can play and read classical music on the

piano.” Readers with “any information

about the man’s identity” were asked to contact a social worker named Michael

Camp of the Rapid Response Team at the hospital.

This

moderately stated notice was illustrated with an indistinct photograph of a

face, pulled back and staring at the camera from behind a barricade of defensively

gathered bedsheets. The poor quality of

that unattributed snap may help to explain why, by the time it appeared, a Kent-based photographer named

Mike Gunnill had already received a call from the Daily Mail picture desk informing him that ‘a man has been found,

he isn’t talking.’[v] Like the Sheerness-Times

Guardian, the Mail had been

alerted to the story by Michael

Camp, who explained that the clinicians needed

help in identifying their patient.

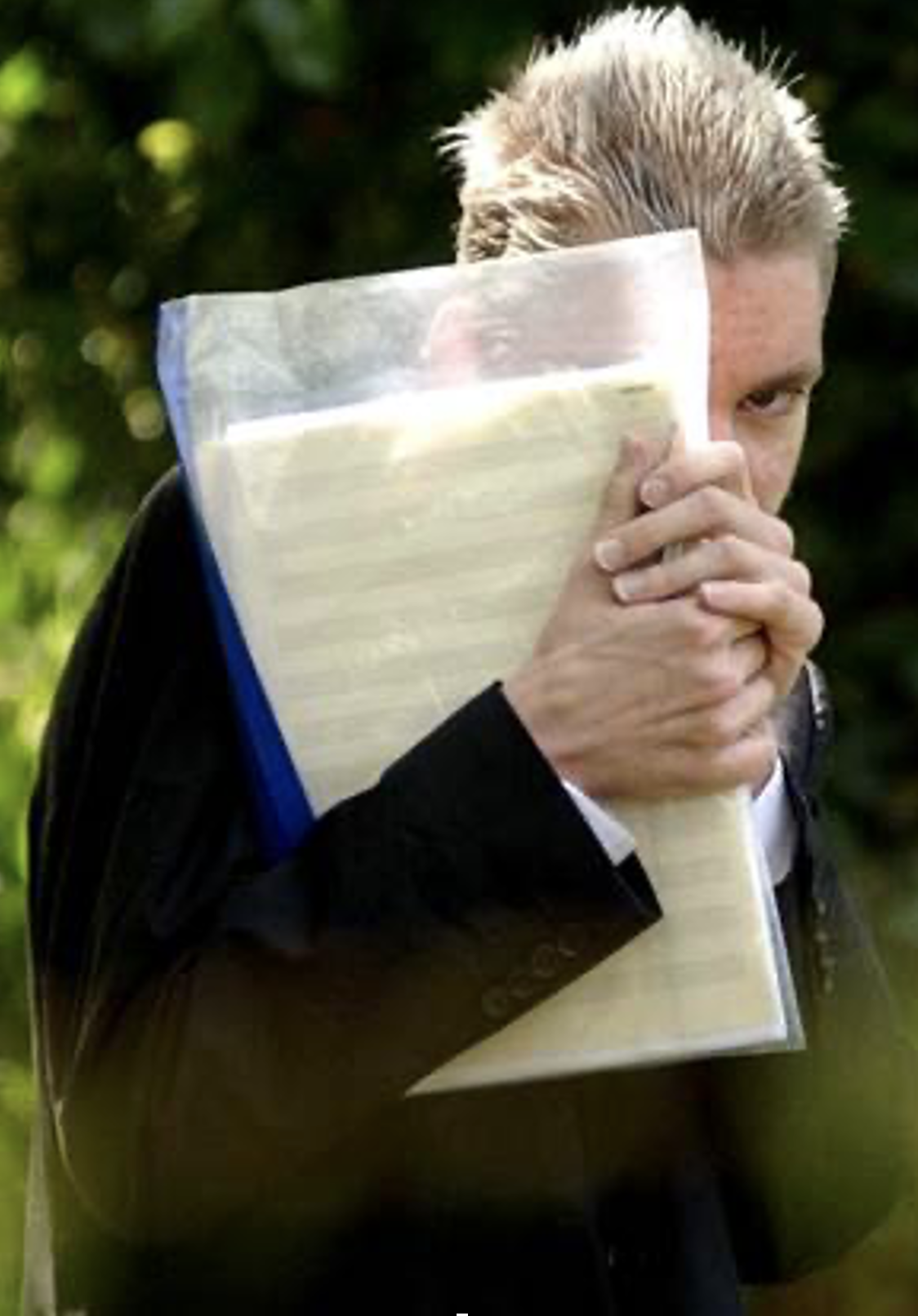

Meeting up with Camp at the hospital, reportedly on May 6th, Gunnill

had struggled to photograph the man, who ‘covered his face every time and

started to become distressed.’ As the

photographer would later explain to a French journalist, he “screams and cries

like a baby when he sees someone new.” He also stared around “as if seeing the

world for the first time.”[vi]

Realising that Gunnill

might fare better when he took the man out for his daily walk, Camp had shown him

a place “partly hidden by trees,” and told him to be standing there with his

camera ready at the appointed time.

Gunnill, who seems by now to have been working as an NHS-assisted

paparazzi, managed to get five shots (only three of which were in focus) before

‘the mystery man’ spotted his lens and took evasive action. The photographs

show a tall, pale, stick-thin, and lightly bearded figure with spikey upthrust hair, wearing his by now dried-out suit

![]()

Photo: Mike Gunnill

with a white shirt and every possible button done up. In one of Gunnill’s artfully stolen shots,

the solitary figure sees the camera and stares back, clutching his plastic

folder of music in both hands as if it were the only thing that stands between

himself and some dreadful dissolution.

In others he shields his face completely, or glares at the camera from

behind the folder with a single fierce eye.

Having sent his pictures

to the Daily Mail Gunnill heard

nothing until two weeks later when his contact at the paper called to explain

that publication was proving difficult because ‘several Associated Newspaper

executives thought my mystery man was just a “****** asylum seeker trying it

on.’ Since the Mail was still being bothered by ‘that social worker’, who was allegedly

phoning several times a day to ask when the story would appear, Gunnill was

urged to take his pictures elsewhere. The

photographer had then spoken to a journalist, described as the ‘well-respected’

Richard Creasy, who wrote the article that eventually appeared, alongside one

of Gunnill’s shots, in the Mail on Sunday on May 15. While the main article was on

the inside pages, a small version of one of Gunnill’s photographs was also printed

on the front page. According to

Gunnill, the picture stayed there for ‘the first three editions’ but was then

‘spiked’ thanks to the suspicions of senior executives, who remained convinced

that the man was “just another asylum seeker” bent on ripping off the British

tax-payer.

The Sheerness Times Guardian may have been

first with the story, but it was Creasy’s article, captioned ‘Who is this

silent genius they call the Piano Man?’, that projected Sheerness’s latest washed-up waif

into the wider world. The dishevelled man,

who was said to have “turned up in a rainstorm”, had by this time become ‘immaculately

dressed in an expensive dinner suit, shirt and tie’. As for the doctors and carers at the Medway

Maritime Hospital, they remained puzzled both by his distraught condition—manifest

in rapid breathing and acute terror of other people—and by his protracted

silence. Creasy, who had interviewed

Michael Camp, described how the carers had got their best clue so far when they

left their charge alone with a drawing pad and pens ‘in the hope of a

breakthrough’. Returning an hour or so

later they found he had produced a sketch of a grand piano, also photographed

by Mike Gunnill, and drawn a paper keyboard on tacked-together sheets of

A4. They had then taken him to the

piano in the hospital chapel, and been amazed when he ‘began to play long passages

of classical music.’

These recitals prompted the realisation that

their now mysterious as well as unidentified patient had, as Camp was

quoted as saying, been found ‘dressed as if he had come from a concert’. He may, as the social worker added, ‘have had

a traumatic experience that has led to him losing his memory or suffering a

breakdown. . . All we know is that he appears to be a professional pianist of

exceptional ability, and has amazed

everyone who has heard him. He plays for hours every day from memory and from

sheet music he has written. It is

difficult to stop him and he sounds concert standard.’ Camp admitted that, even though it was hoped

that the man’s ‘so special’ gift for music would surely help friends or

relatives to recognise him, enquiries sent to ‘concert organisers and musical

groups’ had so far drawn a blank.

Following publication

of Creasy’s article, which gave Sheerness’s smudged and sheet-clutching figure new

life as ‘the Piano Man’, the story of this now enigmatic stranger was quickly

taken up by other papers and media organisations in Britain and, indeed, around

the world. The tide of reportage quickly

became a matter of acute concern to the managers at the West Kent NHS and

Social Care Trust. Camp himself, who

could never have anticipated this explosion of interest, would be suspended from

work until it was established whether he had acted with the appropriate

permissions as he sought to discover the identity of his charge.

Mike Gunnill, the

photographer who was now the only available source of information about the launching of the Piano Man, remembers how his phone went crazy.

He would pick it up in the middle of the night and find himself talking

with Japanese papers and television channels, people who were entirely convinced

that the Piano Man was actually an

‘alien’ who had dropped in from outer space or another dimension. One Japanese

company made a pile of money by stealing his photograph and printing it on T-shirts

with the slogan ‘Who am I?’ written under it.[vii]

Meanwhile, journalists and television crews from

farflung places were finding their way across the Kingsferry Bridge to the Isle

of Sheppey, where they carried their questions into the Sheerness Times-Guardian’s office on the

High Street. Jérôme Cordelier, who worked with the French

news and political weekly Le Point, was

among them. No mere pedlar of

sensations, Cordelier was a man of broad social sympathies who, only a year or

so previously, had joined the president of France’s Emmaus movement to write a

‘Manifesto against Poverty’[viii] renewing the plea for an ‘uprising of kindness’ made on behalf of the homeless

and derelict more than fifty years earlier by that same founding president, a

Resistance hero and priest named Abbé Pierre who went on to be revered as ‘the

conscience of France’. Cordelier discovered

Sheerness to be a “sad port in South-eastern England, battered by winds and

disfigured by industrial facilities.”[ix] He also found the Sheerness

Times-Guardian’s staff reeling in amazement at the sudden efflorescence of

international interest in their normally ignored island. ‘This is really bizarre, no?’, muttered a local

reporter, pointing to a Japanese television crew that had turned up on the High

Street at about the same time. The editor, who had just taken a call from the Los Angeles Times, is likely to have

shared his reporter’s sympathy for Riichiro Harayama, of the Tokyo Broadcasting

System, who had flown for 20 hours only to be told that there really was nothing

for him to see in Sheerness. The shingle beach known as The Leas was still

there, of course, perhaps attended by a few paddle-boarding families and the odd dog walker, but what else could

be said about the place? The Sheerness Times-Guardian had 27,000 readers on and around the Island but their request for information

about the stranger had received no response at all. It was, so the paper itself would conclude,

‘pretty safe to say that the Piano Man has no connection with the Island.’[x]

Stepping out of

the Sheerness Times Guardian’s office, Cordelier soon discovered that this

sudden wave of offshore interest seemed frankly incredible elsewhere in Sheerness

too. The people he asked about the sudden fame of their unknown visitor appeared

to be ‘torn between compassion, desolation and a good laugh.’ In the White House pub, outside which the

newly dubbed Piano Man had been apprehended, Cordelier encountered a

saleswoman named Debbie, who insisted that the fellow had earlier come into

the grocery store where she worked, staring around wide-eyed but not buying anything:

‘he gave the impression of seeing but not thinking.’ The publican, Mike

McAlister, took a more downbeat view of the stranger. ‘We are,’ as he explained for the French

journalist’s benefit, “located midway between the Channel and the mouth of the

Thames, which leads to London...” He had

little doubt that the Piano Man was ‘part of a group of illegal immigrants. We

get many here . . .’ This experienced grader of human flotsam reckoned that the

smugglers were ‘surprised by the police boat, and threw them into the sea.’

The pages of the Sheerness Times Guardian confirm Cordelier’s

account of the amazement that filled the paper’s office as their apparently

incidental story was taken up in the world beyond their shunned and much maligned

island. By May 15, the paper had adopted

Gunnill’s superior photograph and also the upbeat new interpretation of the

Piano Man. It noted that the National Missing

Person’s Helpline had received 160 calls since ‘national and international

media’ had picked up on the story.[xi] By 26 May, the Times-Guardian was getting a little possessive, claiming that ‘Our

Piano Man is world famous’[xii] and describing how its little office on

the High Street had been ‘inundated’ with

calls from journalists: ‘I’m used

to asking the questions, not answering them,’ muttered one bemused reporter.

Having lost control of its story, the local paper was now running to keep up. Far from standing back from the ‘rumour mill,’

its reporters could only repeat the questions that were now being asked around the world — ‘Where has he come from? Why is he not talking? Was he thrown from a

boat or did he jump ship?’ — before adding a suspicious thought that just might have

been entirely its own: “Is he secretly trying to gain recognition for his

musical talents?”

Two developments

were necessary for the story to take off as it did, and Creasy’s article for

the Mail on Sunday had successfully initiated

both of them. The drama had to be raised

above the never entirely vanquished suspicion that the Piano Man was, in the Sunday Express’s headline, ‘Just a

Clever Conman’ trying to enter Britain illegally and ‘playing the system as

well as he plays the keyboard’ (12 May 2005, p. 45). The story also had to be

removed from the Isle of Sheppey (’an odd outpost of Kent’, as the Sunday Times would call it), and re-voiced

as a universal allegory about, in the quoted words of an already interested

Hollywood producer, ‘the fragility of the human mind, the nature of

communication, and the importance, or unimportance, of identity.’ The producer in question, Bard Dorros of Smart

Entertainment, further explained that ‘great stories raise, and often attempt

to answer, questions about the nature of the human mind, how it works, who we

are. The Piano Man’s story frames that in a mystery – what is at stake is this

man’s identity.’[xiii] So it was that Michael Camp’s silent patient had emerged from

the Mail on Sunday as a latter day

version of Everyman, adrift in a world in which he could no longer find his

bearings. Emancipated from the contingent

misery of its origins in Sheerness, the story was eagerly embraced as a fable

proving the proximity of art and reality.

That is how it seemed to the novelist, Chris Paling, who sat down to

write an article for the Daily Telegraph, claiming that he himself had already written the ‘Piano Man’ in his

just published and duly plugged novel, in which a forgetful man crawls out of

the sea and heads into a nearby town.[xiv]

As the fable expanded

into a global allegory, it also threatened to devour the ‘very highly strung’ young man who was by now lodged at Little Brook Hospital at the edge of Gravesend. Journalists, who were now the missionaries of the

expanding fable, tried frantically to winkle further details out of more

or less reluctant carers and managers. It was reported that all the identifying

labels had been cut or otherwise removed from the Piano Man’s clothes.[xv] It was disclosed that the ‘silent genius’s’

carers had tried various techniques alongside the Medway Maritime Hospital’s chapel

piano, which the Sunday Times had

inspected and was pleased to identify as a Challen 50 key model. They had brought in interpreters in an

attempt to engage the silent genius in Russian, French and German. They had showed him a map of the world and been

encouraged when he ‘doodled on the coast of Sweden’. Reporters also teased further

concessions out of Michael Camp, who told the Sunday Times that, when agitated, the Piano Man tended to ‘hyperventilate’

at a rate of 70 or 80 breaths per

minute: ‘I’ve never seen anyone breathe

like that. Anyone else doing that for a bit might faint, but he does it for as

long as he is agitated.’ And that was by

no means his only peculiar mannerism: ‘He never walks in a straight line. If he

enters a room, he will not walk across it. He will walk round the room, keeping

his back close to the wall. This way he maintains

eye contact with everybody. If more than

one person is in the room, his eyes flicker from one person to another.’ ‘Locals

on Sheppey’ meanwhile were said to persist in the suspicion that the Piano

Man had ‘slipped off a passing vessel’ like so many others before him.

Enquiries had been made with the owners of ships passing into Sheerness port

that night – a vessel from Norway, a container ship from St. Petersburg, another

from Sweden. Although no-one had been reported

missing, ‘it is, of course, possible that he was a stowaway.’

The Sunday Times also

revealed that Sheerness, where ‘strangers tend to get noticed’, had seen rather more of the Piano Man than

was initially understood: ‘After about two weeks in hospital the Piano Man had

been transferred to a Sheppey hostel’ (the obvious candidate is a place named ‘The Foyer’, almost beside Sheerness-on-Sea’s railway station, which was not

a secure unit but did have staff at hand). There he remained, it was suggested, until

one night he walked out. ‘He was spotted

sidling along the street in Sheerness, with his back against the shop windows,

trying to keep his eyes on anybody who came near.’ The police had picked him up

again and he was returned to the Medway Maritime Hospital, where he had this

time been sectioned under the Mental Health Act and transferred to his present

residence the Little Brook psychiatric hospital at Gravesend.

Learning that

there was no chapel piano at Little Brook, the Sun made the mistake of trying to donate an electric keyboard to be

placed in the Piano Man’s new room to make the story true: ‘he obviously wants a proper piano or

nothing,’ Camp told the rival Sunday

Express of this rejected offer.[xvi] Meanwhile, the Piano Man’s recitals kept

getting better and better. There was

talk of the young maestro’s ‘meandering, melancholic airs’, and of the brilliance

with which he cruised through Lennon and McCartney tunes while girding himself

up for ‘a complete rendition of Swan Lake’[xvii].

Piling it on

As the story spread through the summer, the Piano Man was the subject of a

great efflorescence of speculation in which the suspected illegal

immigrant and NHS scrounger was converted into a tortured artistic

genius—a fellow of unique brilliance who must, so some of his carers appeared to have

concluded, have suffered some sort of

nervous breakdown after a disastrous performance. Indeed, he’d not even had time to change out

of his concert clothes before stepping onto the boat from which he must have leaped,

distraught, as it approached the Thames estuary. The search for the “mystery man’s”

identity produced an escalating array of contenders. The National Missing Person’s Helpline was said to have received 400 calls by 18 May (Guardian). The Mail

on Sunday followed up its first article with another, claiming that the man

was called Tomas and had once played in a Czech rock band. Other contenders included a performance artist

of uncertain nationality who had been seen in France or Spain, a Swedish pianist, Martin Sturfalt, who turned

out to be in his flat in Stockholm after all, and a Canadian drifter known as

‘Mr. Nobody’ who had once tried to enter Britain illegally. Various women

announced themselves convinced that the Piano Man was their missing boyfriend

or husband. Hundreds of names were put

forward. If Mark Lawson is to be

believed, so many Hollywood producers were interested in his ‘story’ that the doctors

and nurses could hardly get through the crowd at his bedside (Guardian, June 18).

There was also a flurry

of armchair diagnosis. One psychiatrist, Dr Felicity de Zulueta, who had never met the

victim of her assessment, was nevertheless confident that he had been hurled into a

‘fugue-state’ by trauma and may only have been able to access ‘the right hemisphere of his brain through the

piano.’ (Sunday Times). Pop

psychologists also took to the prints to offer their interpretations of his plight. Oliver James was in little doubt that

the Piano Man was suffering from a ‘borderline personality disorder’. Dr Judith Gould of the National Autism

Society recognised him as belonging on her organisation’s spectrum but at least requested

access so she might pursue her diagnosis more closely. As the legend grew it attracted

the meta-commentators too. Not content with commending the man’s

‘glorious, enchanting music,’ the allegedly Lacanian analyst, Darian Leader, used theTimes to declare that the story,

which was ‘Striking a chord in all of us,’ was made of the ‘stuff of folklore

and myth’. It had also, so this expert confidently

remarked, activated ‘the common fantasy of escaping a humdrum existence’ (Times, 21 May).

This heaping up of speculative theories,

in which an unknowing and apparently terrified psychiatric patient was drafted

into service as an involuntary hod-carrier for the world’s fantasies, went on

for the best part of four months. By late July, the doctors were reduced to

wondering whether their mute patient’s voice box was damaged, or had even been

removed: they hoped to investigate but were impeded by the difficulty of getting

his formal consent for an endoscopic examination. On 8 August, the Independent reported that the NHS were

worrying that “the talented musician in a wet suit” might never be identified”,

a fear that was reiterated by the Sheerness

Times Guardian on 18 August.[xvii].

All this, however, came to an abrupt close the following morning, when a nurse went into the Piano Man’s room and asked routinely, ‘Are you

going to speak with us today?’ Unexpectedly, the mysterious patient looked across and replied ‘I think I will’. He went on to identify himself as a

twenty-year old Bavarian named Andreas Grassl: a farmer’s son who, far from having

been ‘washed ashore with no identifiable co-ordinates’ as Darian Leader had

surmised, had actually travelled to England by Eurostar from Paris, and had

been trying to drown himself in the hours before he was picked up by the

police. Informing the hospital staff that

he had two sisters and was gay, he also announced that he had only drawn a

piano because ‘it was the first thing that came to mind’. As for his musical skills, the hospital

chaplain had been right to warn the Sunday

Times that he really could not play the piano very well at all.

The

embarrassed hospital managers were careful to ensure that, by the time the press was informed of this development, Andreas Grassl was back with his dairy-farming

parents in the tiny village of Prosdorf in Bavaria, whence he would only speak

in carefully measured statements issued through the family’s solicitor. He explained that he had known nothing of the

media storm brewed up around him, and, having thanked the psychiatrists and nurses

who had looked after him during this distressing episode, and also the many sympathetic people who had written

to him while he was in hospital. He was said to have announced that he had no memory of how he had reached Sheerness. He wanted no further contact

with the media and intended to withdraw in order to consider his future. By the time the gay news service Pink News revisited the story two years

later in 2007, Grassl was said to be living in Basel, in Switzerland, and studying

French Literature at the university. By

then reporters had found various of his former friends and acquaintances

who allegedly spoke of the difficulty of growing up gay in a conservative Bavarian

village, and who suggested that his crisis had become acute in the French

coastal town of Pornic, in South-Eastern Brittany, where he had gone to find

work and entered a relationship that had gone wrong.

The British press was by no means

unanimously content to have its summer fable so rudely breached by reality. Some commentators used merely plangent

terms to lament the sudden disenchantment caused by Grassl’s recovery. In a leading article for the Independent, Charles Nevin, who claimed to have dreamed that the

piano man was another wandering genius like Paderewski, regretted that ‘a little touch of magic and mystery is

no more’. Other papers, and not just the

old tabloids, reacted angrily to the sudden desublimation, as if they had been grievously

let down by Grassl, who had surely proved quite unworthy of the fame they had so generously bestowed upon

him.

The fable had all along been pitched against

the now resumed suspicion that the piano man was actually a ‘f*****g asylum seeker’ or, at best, a trickster perpetrating ‘some performance art prank’ (Sunday Times). In this disillusioning light Grassl, who had unwittingly demonstrated that already in 2005 a foreigner seeking help in England had to be a creative genius to avoid the

suspicion and hatred not just of large sections of the British press, but also of the

Home Office under the Labour Home Secretaries David Blunkett and Charles Clarke, was now multiply denounced as a ‘fraud’ for not being authentically mute

and a ‘sham’ for not really being able to play the piano either. It was alleged that his ‘glorious,

enchanting music’ (Darian Leader) was much worse even than the ‘good amateur’

level claimed by the hospital chaplain and had actually consisted of ‘hitting a

single key repeatedly’. Grassl, who was

surely not having a go at Terry Riley’s ‘In C,’ was nothing but a ‘suicidal gay German,’ no

longer a pianist but ‘just a fiddler’ who had made disreputable use of his past

experience as a ward orderly in Bavaria to act mad in order to freeload on Britain’s

cherished NHS. As Grassl’s journey back from maestro to scrounger proceeded, various papers gleefully declared that the

Health Authority was considering legal action to recover the costs of his care:

a wishful recommendation that went nowhere, thanks partly, as may be

surmised, to the clinicians who appear never

to have doubted that Grassl had been in the midst of a genuine personal crisis

that was now at least partly resolved.

Many of the

higher commentators,who offered their retrospective thoughts on the meaning of

this drama, had shared the assumption that the story had been so evocative

because the Piano Man represented what Darian Leader had called a ‘blank

canvas’ onto which people felt invited to project their own longings and fantasies (Times, May 21). In reality, ‘canvas’ was not the medium that had

supported the clouds of speculation, and neither was the screen on which they

were projected in any way ‘blank’.

In the words of

the Sunday Telegraph, the story of

the Piano Man was ‘strangely cinematic, from the shock of his dyed blond hair

to the unusual formality of his attire.

He is a walking plot yet to be unravelled.’[xviii] In the early weeks, that unravelling had

taken various forms, each one prompted by a different film. Many, including the Mail on Sunday’s Richard Creasy and some of Grassl’s carers, saw the Piano Man as a version of the Australian film Shine (1996) – which turned

the tormented pianist David Helfgott into an embodiment of what an

American psychiatrist diagnosed as ‘movie madness’: i.e. a ‘celluloid amalgam of schizophrenia,

manic-depression, post-traumatic stress disorder and idiot savant’ (Kenneth

Paul Rosenberg, M.D., letter to the editor, New

York Times, March 15, 1997). For

those inclined to emphasise the ‘idiot savant’ in this winning mix, corroboration

was provided by Dustin Hoffman’s performance as Raymond Babbitt in Rain Man (1988). Writing in Le Point, Jerôme Cordelier, added a more recondite film

- The Man without a Past (2003) by

the Finnish director Aki Kaurismäki, the hero of which is a welder who loses

all knowledge of himself after being beaten up and robbed a few hours after stepping

off a train in Helsinki, and then builds a new life among the city’s

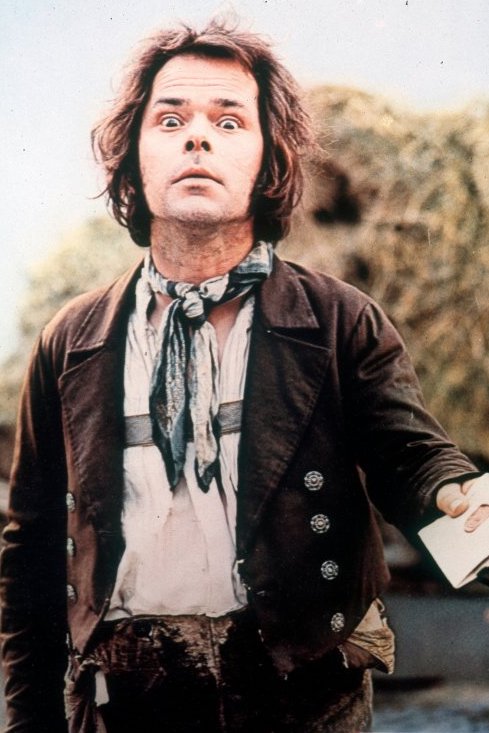

container-dwelling outcasts. Other commentators, in Germany especially, reached further back to Werner Herzog’s historical drama The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser (1974), in

which the people of Nuremburg wake, on

the morning of 26 May 1828, to find a strikingly inarticulate young man

standing in a small square and holding out a letter explaining that he had been raised in almost complete isolation in an unnamed village

on the Bavarian border and wished to become a cavalry officer like his alleged late

father.

Bruno S as Kaspar Hauser in The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser

Bruno S as Kaspar Hauser in The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser

The story may well

have demonstrated the power of film to shape public

perceptions. Yet the pictures that had

done most to keep the “Piano Man” aloft as he was pushed and pulled through

this storm of contending scenarios were actually of a decidedly

static variety. Mike Gunnill’s

photographs travelled with the story as it went round the world. In the most evocative example, a cropped

version of which was used by the Mail on

Sunday to accompany the inaugural article of May 15, the

Piano Man has the caught-in-the-headlights look characteristic of paparazzi

shots. Yet it is the contest between the predatory lens and Grassl’s only just retaliatory

stare that gives the photograph its compelling quality.

![]()

Here, to be sure, is the Piano Man as something other than the merely

abject sufferer of psychiatric illness: a pale but surely still minded figure, surrounded

by leafy green nature rather than a pale institutional room with all the

ligature points removed and slumped figures watching daytime TV. Gunnill’s photographs had helped to confirm this idea of

the Piano Man as a young genius in trouble.

The man in his most widely circulated image had resonated with the memory of other wandering pianists - and why not Chopin as well as Padarewski

? – but why not also with a wider tradition of genius-melancholics, from the punkish variations produced by Malcolm McLaren or in Julien Temple’s films, back through Syd

Barrett to Antonin Artaud as a schizo-tourist in Ireland, the solitary

melancholic males of Edvard Munch or August Strindberg in his Inferno period. Indeed, since we are now following those who spent the summer of 2005 piling it on, why not add the windswept wanderer

in Kaspar David Friedrich’s painting

‘Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog’ (1818)?

The Island Reclaims its Story

According to the

retrospective article published in Pink

News on May 1 2007, Grassl’s closing

words on this drama before he got on with his literary studies were

wishful as well as decisive: ‘That Piano Man stuff, no-one is interested in

that anymore.’ Certainly, the discovery

of Grassl’s actual identity put an abrupt end to the interest of the Hollywood

producers, who were quick to move on, leaving the suddenly abandoned “story” to be

picked up years later by a small London-based theatre company named AllthePigs,

whose members premiered their own production, ‘Piano Man’, towards the end of

2014. Promoted as ‘the story of a man whose language was silence’, the show, which I saw as it passed

through the studio of the Marlowe Theatre in Canterbury on 7 May 2015, turned

out to be a well-paced production, which nevertheless seemed to me a little too much on the side of Darian Leader’s

suggestion that the Piano Man was a ‘blank canvas.’

![AllthePigs Publicity photo for 'Piano Man']()

All the Pigs, publicity photo for ‘Piano Man’

The performance

was warmly received by an audience that did not appear remotely troubled by the fact that the play gave

no quarter to the

reporters of the Sheerness Times Guardian. Rather than differentiating between the local

coverage, which was truthful, and the national and international coverage, which was so largely not, they came up with a composite figure of the journalist as a

drunken falsifying Sheerness hack—‘another day, another fingernail lost to the

scraping of the barrel’—who embraces the story as welcome relief from the

usual local news (‘Sheppey farmer claims cows can talk’ etc.), and who is forced, quite unfairly, to serve as a representative

of the ‘offshore’ press too.

The Isle of Sheppey has long been the butt of easy

jokes in mainland Kent, and the Sheerness

Times Guardian may indeed have its own idea of what constitutes a scoop (’Second

escape from Cattery’ etc). However, there

is surely more to be said than that.

Indeed, the local context, so carefully scraped off the story by the mainland

commentators, still holds the key to a proper understanding of the entire episode.

Susan Harris, whom I met at her home in Queenborough

High Street, was among the Sheppey residents who had watched the rise and sudden

fall of the Piano Man over the summer of 2005. She had picked up the Independent on 23 August, a day or two after Grassl revealed his name, to find herself

reading Charles Nevin’s leading article lamenting the discovery that the Piano Man, whom he had preferred to think of as a ‘splendidly magical mystery’— ‘tall, sad, shyly staring, haunted and mute’—was

no more than an ordinary young man who had ‘played like Eric Morecambe’ but actually been

‘perfectly able to talk’ all along.

Nevin, who could not be accused of displaying a great deal in the way of

sympathy or psychological insight in this article, regretted that Grassl’s recovery had wrecked

a story that had seemed just like an old-fashioned Hollywood script—‘minus

Sheppey’ as he added in brackets. That

qualification had irritated Susan Harris, who found her suspicions confirmed

as Nevin went on, all too predictably, to joke about car boot sales. ‘What, she wanted to know, ‘makes the Isle

of Sheppey a “comedy setting”’? How

much did Nevin actually know about ‘this place, so often the butt of puerile

digs by people who know little of the island?’

As for Grassl, who had become the victim of so much airy philosophizing

and comment around the world, Harris’s was emphatic: ‘The young man came here

thinking of taking his life but fortunately there were kindly people on hand to

help him. He might not have fared so

well on a beach elsewhere. I know the Island people will now wish him a long,

peaceful and happy life.’

Susan Harris had lived on the Isle of Sheppey

since the early 1960s. Having previously training

in dress-design at Nuneaton Art School she had settled on Marine Parade in Sheerness with

her husband, the island artist Martin Aynscomb-Harris. She had raised a

family there, completed an Open University degree, and then gone on to work in

adult education. When I talked to her about her letter of objection (on 13 July 2015), she explained that she had, for many years, made a point of countering

those who sneered at Sheppey, or preferred to pretend it didn’t exist. She

cited the recently published Spring issue of a quarterly church magazine named Outlook, published by the Diocese of Canterbury: I looked it up after we talked and there on the second page, just

as she had said, was an outline map of Kent from which the Isle of Sheppey was

entirely absent. This may have reflected inept page-making more than a deliberate cleansing

aimed to confine the Church of England’s presence to more

prosperous parts of the county, but for Harris it seemed all too symptomatic of a wider disregard for

the Island. Repeatedly, over the years, Harris had gone out of her way to

insist that it is possible to live on Sheppey without being degenerate, inbred,

stupid or otherwise deserving of the sneers mainlanders so often aim at the

island’s ‘swampies’. Her point, in mounting these defensive interventions, was that for all the insults and injuries suffered by its inhabitants,

‘there is a lot of humanity on the Island.’ Considering that she had been a neighbour of Uwe Johnson’s during the latter’s residence at 26 Marine Parade, Sheerness, her comments remind me of the things the embattled formerly East German novelist used to say against stereotyped western ideas about life in the DDR.

Grassl to Buzi