Patrick Wright

The Praesidium

Pick Your Own

“Wright is a wandering, disestablished scholar whose method is to walk and talk.”

Neal Ascherson, London Review of Books“ I don’t think there’s been a more original British cultural historian over the last forty years than Patrick Wright . . . he’s always textured, droll, a diviner who addresses topics and intuits significance years—often decades—before other more garlanded commentators.”

Sukhdev Sandhu, The Colloquium for Unpopular Culture, New York University.

“This is the most depressing book I have read in years... It is ghastly to imagine the sort of ghoul who could wring so much as a furtive snigger from the calamities Wright logs.”John Carey, Sunday Times

“The disturbing questions he raises are at the heart of our current crisis of national identity.”

Claire Harman, TLS“Wright . . . is not a biographer or a journalist but a sort of spirit-ethnographer, patient and attentive to change and complexity”.

Ben Ratliff, 4Columns“A work of wit, style and waggish erudition. I was informed and delighted by its originality.”

John Le Carré (on Iron Curtain)“The publishers’ blurb states, ‘Tank is not a conventional work of military history.’ Amen to that”

John Keegan, TLS,

“. . . thorough, discerning, compassionate but not all-licensing...”.Max de Gaynesford, London Magazine

"Is there a house of history to stand as neighbour beside Henry James's house of fiction? If there is, Patrick Wright will have a window all to himself, glittering with different, intense and jewelled fragments: a John Piper or Robert Colquhoun of a window."

Fred Inglis, The Independent

“I have owned this book for three weeks now but it looks as if I have owned it for three decades, a condition derived from the number of times I have thrown it across various rooms.”

Byron Rogers, Literary Review

“. . . shrewd, wry and fiercely intelligent.”

William Boyd

Here is a city dweller with the gusto of Baudelaire and the eye of Jane Jacobs who, undeterred by dogshit and bullshit, enjoys the chaotic humanity, the ironic architectural juxtapositions, the esprit de jeu of late twentieth century London.”

David Widgery, Independent on Sunday

“. . . a living national treasure of a rather weird variety: a historian who uses the imagistic logic of a fiction writer in the service of explanation, drawing out the many-sided truth of the past by letting unexpected connections form.”

Francis Spufford, Evening Standard“. . . an unusual historian—following by-ways normally overlooked by these eyes more firmly fixed on the mainstream. We should treasure his waywardness.”

Paul Lay, History Today“. . . a shrewd and cynical commentator.”

Penelope Lively, Daily Telegraph“The historical material he gathers is designed to suggest that if you are saddened by seeing green fields built over, if you oppose giant road schemes, if you think Britain is overpopulated, then you are probably a racist and a fascist, and do not deserve to have your arguments taken seriously.”

John Carey Sunday Times“. . . a sensitive, ultra-thoughtful explorer of [the] national necropolis. With a large torch and copious notes he invites the reader to a number of meandering guided tours well off the main footpaths, some to disreputable tombs ignored by the many official study parties busy on this or that ‘Great Tradition’”.

Tom Nairn, The GuardianPatrick Wright is Emeritus Professor of Literature, History and Politics at King’s College London. Many publishers have fled. No agents have survived. Details and contact here.

@tattery

“Wright is a wandering, disestablished scholar whose method is to walk and talk.”

“The most involving and originally-conceived social history of modern England to have appeared in decades” (Patrick McGuinness).

More about the project ︎︎︎

More about the book ︎︎︎

Shona Illingworth’s Sound Work for Estuary Festival 2021︎︎︎

Another German in Sheerness?

England’s Last Acceptable Asylum Seeker? The Legend of the Piano Man ︎︎︎

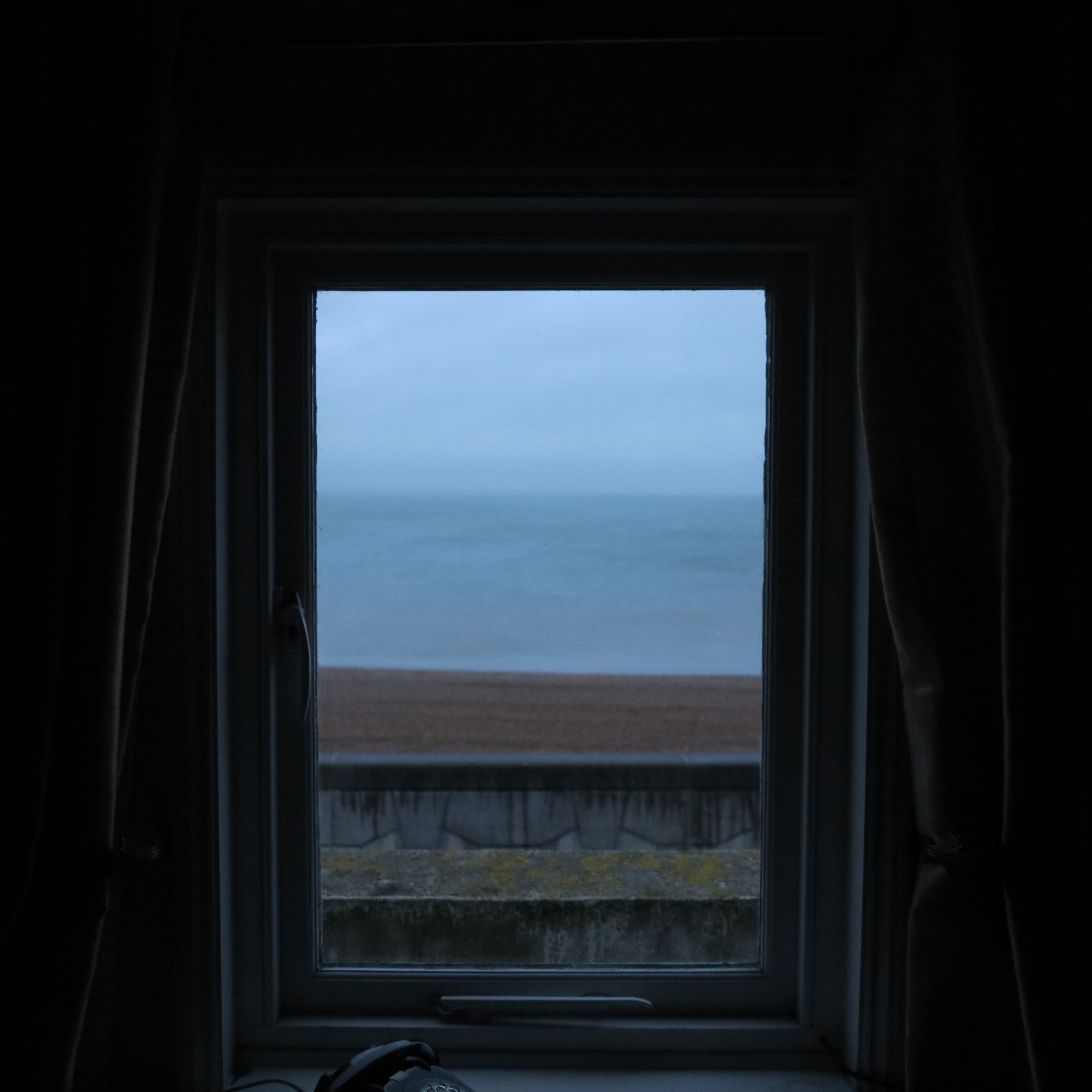

The Sea View

Has Me Again:

Uwe Johnson

in Sheerness

and translations from Uwe Johnson’s German by Damion Searls.

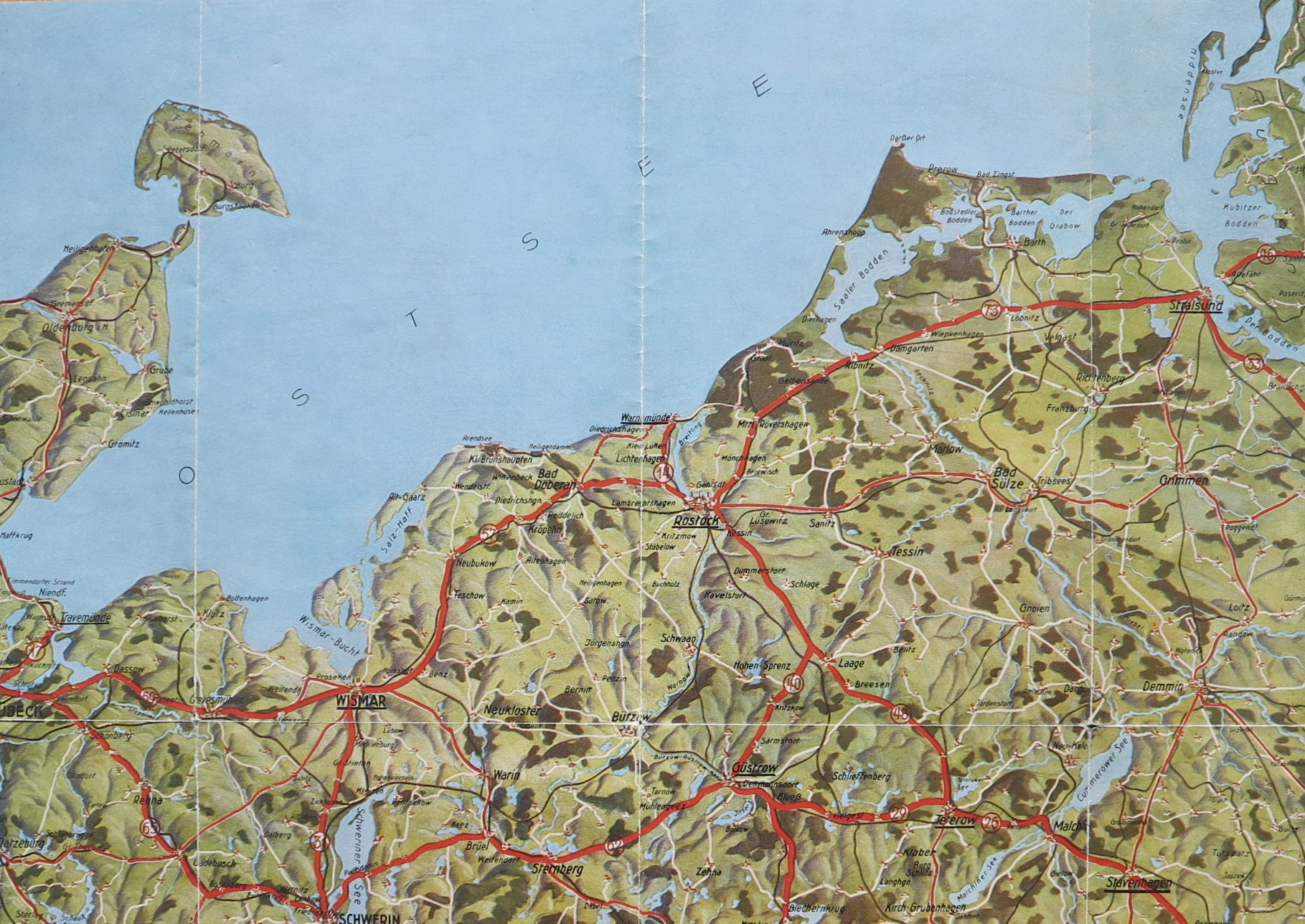

East from Prora

South from Zingst

A Life Beside Rivers

“It would be fair to say that I have a thing for rivers. It’s true, I grew up on the Peene in Anklam, the Nebel flows through Güstrow, I have traveled to and in Rostock on the Warnow, Leipzig presented me with the Pleisse and the Elster, Manhattan is surrounded by the Hudson and East and North Rivers, I also recall a Hackensack River, and for the past three years I have had on offer outside my window the River Thames where it turns into the North Sea”.

— Uwe Johnson, “About Myself” 1977

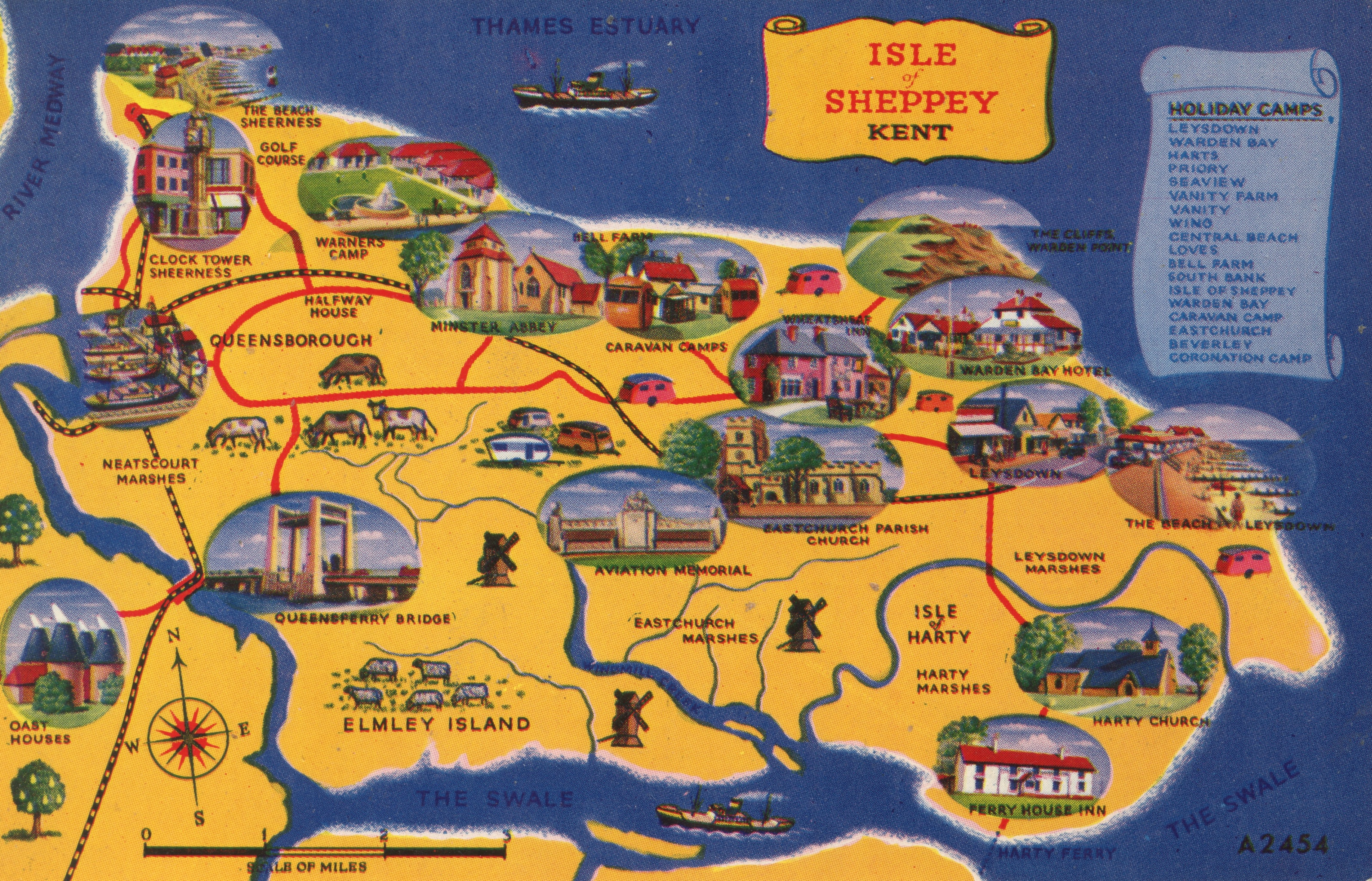

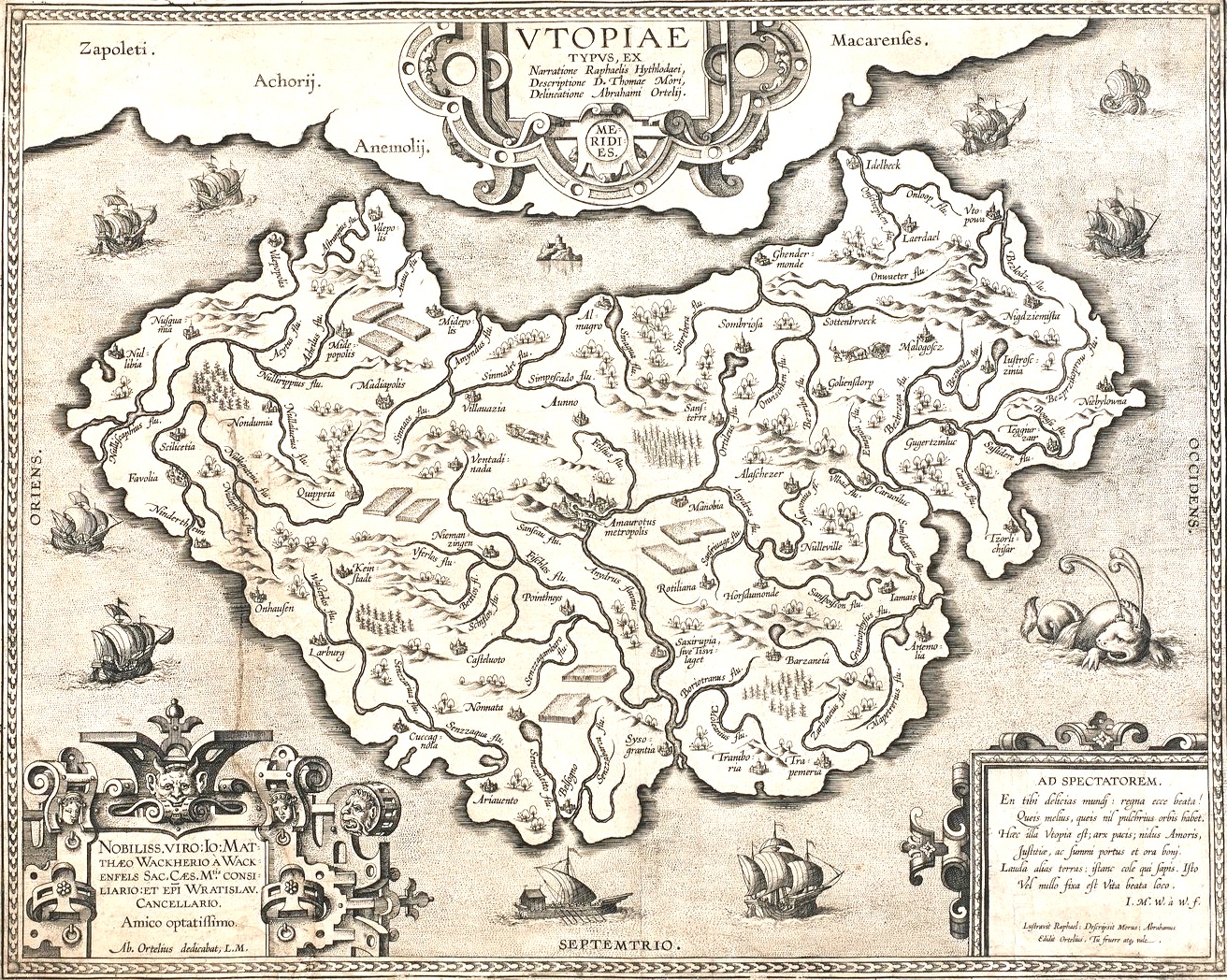

The story of a great East German novelist, and the things he thought and saw during the nine years he lived as a voluntary castaway on the Isle of Sheppey in Kent.

Isle of Sheppey cemetery,

Halfway

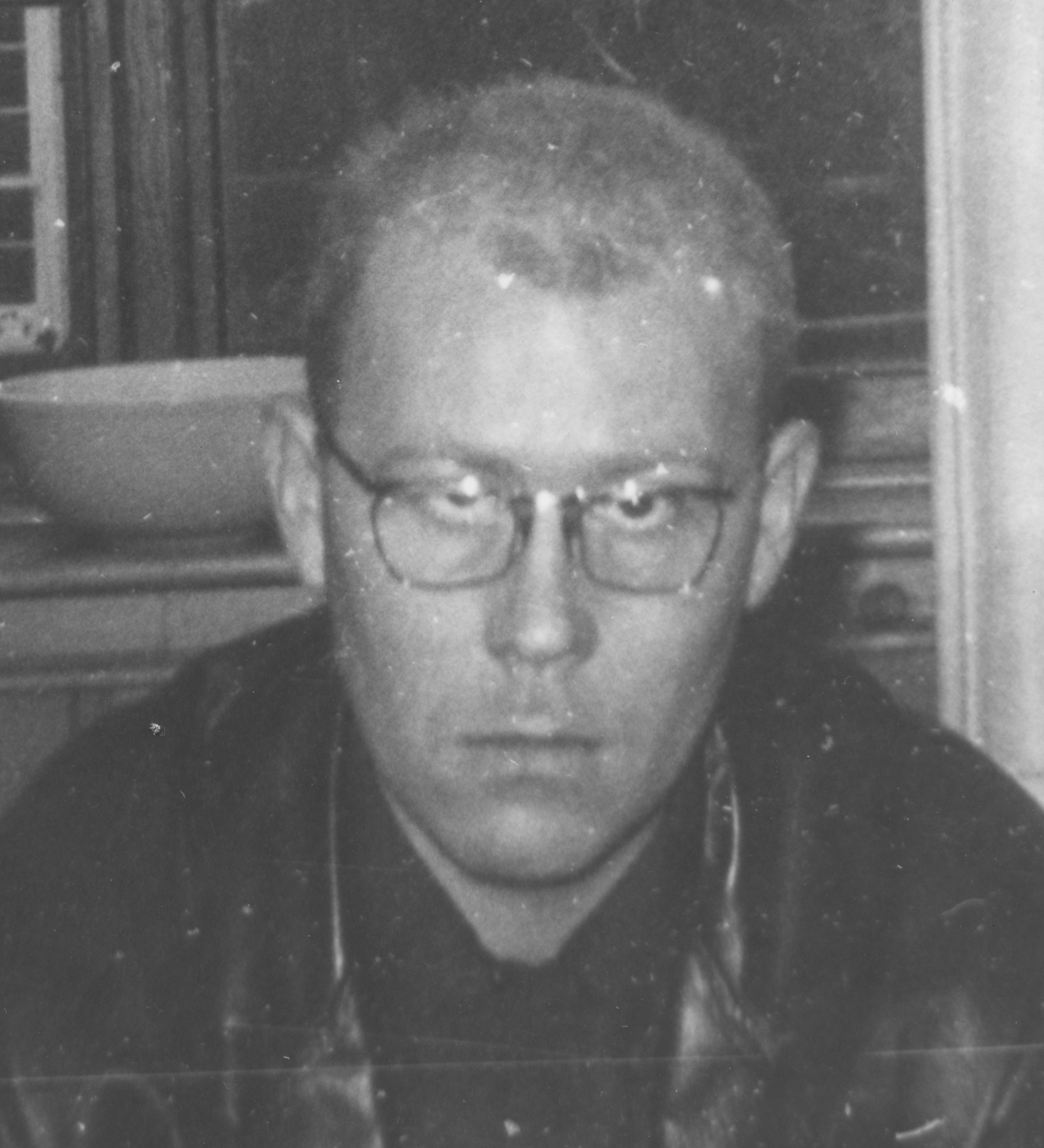

“He was a kind man often misunderstood because of his abrupt manner. He had no time for idle conversation or banalities. He sparred with words. He was a verbal heavyweight, an intellectual whose politics were very much to the left.”

— Martin Aynscomb Harris (artist and Johnson’s neighbour in Sheerness), March 1984.

“Now it’s quiet, the asphalt mirror of Riverside Drive shows us the treetops in their close friendship with the sky.”

— Uwe Johnson, after a storm in New York City, Anniversaries IV

The Writer

Who Chose a New Name

As the Red Army advanced from the East in 1945, Johnson and his family joined the chaotic flight west, finding refuge in the small estate village of Recknitz, in Mecklenburgh,

In 1952 he went to the University at the Baltic port and city of Rostock,

Johnson had been feted as the writer who had done more than any other to create a kind of novel capable of articulating the division of Germany into two states with one terrible and guilty past. Conceived and started during the two years, 1966-1968, during which he lived in New York City, the final multi-volume novel that Johnson came to Sheerness in order to complete, went beyond Germany to engage a world divided by the Cold War. Each chapter of Anniversaries: from a Year in the Life of Gesine Cresspahl would take a day in the year extending from 21 August 1967 to 20 August 1968, and it would be written as experienced by Gesine Cresspahl and her ten-year old daughter Marie in New York City. Structured as a conversation between the two, the narrative would proceed through the events of that momentous year: the war in Vietnam, the civil rights movement, the assassination of Kennedy etc. It would also explore the longer historical experience of the Cresspahl family as it’s generations had lived through the traumas and crimes of the twentieth century in Mecklenburg and elsewhere.

Having started work on this massive novel in New York City, Johnson continued after his return to Berlin. Suhrkamp published the first volume in 1970, the second in 1971 and the third in 1974. It was in order to complete the fourth and final volume that Johnson then decided to remove himself, his wife and their daughter from an increasingly disruptive life in West Berlin and resettle in England. His migration was made possible by the Swiss writer Max Frisch, who offered to lend Johnson the money he would need to buy a house in England where he could concentrate on his work. Having chosen a property on the Isle of Sheppey, he took care to ensure that his neighbours knew very little about him. He would remain in Sheerness for nearly a decade, moving into 26 Marine Parade with his wife and daughter towards the end of 1974 and remaining there until his death, aged 49, in February 1984.

Sheppey scene, between Rushenden Hill and Queenborough

Two Memorials to the Dead

of the Great War

(1914-18)

Barlach’s non-militaristic memorial was commissioned in 1926 and hangs in Güstrow Cathedral. Johnson wrote a dissertation on Barlach — who lived in Güstrow and was among the first artists to be declared “degenerate” by the Nazis — while studying in Leipzig, in the fifties. He had a cast of Barlach’s carving of two “Sleeping Vagabonds” in his house at Sheerness.

Sheerness’s memorial to serving men and civilian dockyard workers lost in the Great War, as photographed on 26 July 2013. The picture at the base shows Fusilier Lee Rigby, murdered by Islamists at Woolwich seven weeks earlier. Johnson used this monument as an orientation point for visitors making their way to his house from the railway station opposite.

Man, Reef or “the Brazen Edge

of Our Crazy World”?

As friends and acquaintances in Germany already knew, Johnson could be a challenging man: volatile and yet blunt too, and sometimes completely inaccessible. The initially East German writer and politician, Gerhard Zwerenz, described him as “a statue of lost cultures” like the “inscrutable monoliths” of Easter Island. After visiting the Johnsons shortly after their arrival in Sheerness, Gunter Kunert looked back to glimpse him waving from the doorstep: a teetering “colossus” who might at any moment fall and break over his own wife and daughter. Though a unique example of the type, “Charles” was by no means the first brazened-off twentieth century man to take refuge on the Isle of Sheppey.

The Bush of Memory

Fischland, Staten Island, Isle of Sheppey?

Johnson arrived in England from West Berlin, but he came with memories of other places too: the flat Baltic landscapes of Mecklenburg and Western Pomerania, to be sure, but also New York — a city that stood at the centre of Anniversaries, the four-volume novel he would eventually complete in England.

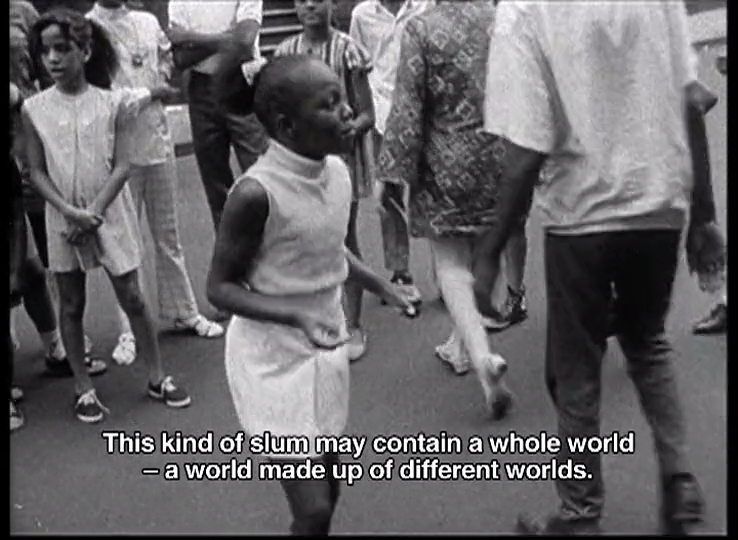

While living on Riverside Drive on the Upper West Side in 1968, Johnson had written and read the text for ”Summer in the City”, a film by the German-born American director Christian Blackwood for West German television.

Blackwood’s original idea was to show Johnson talking with people as he led the camera around the Upper West Side he had come to know while living in an apartment building on Riverside Drive. He eventually decided against appearing in the film, instead providing Blackwood with recommended locations and writing the text he then read as the film’s commentary. In this he praises the activism and the diversity of the “slum” he would, in Anniveraries, liken to a mobile jellyfish slithering about among the brownstones. He remains silent when Blackwood takes his camera into the transvestite world.

Blackwood’s original idea was to show Johnson talking with people as he led the camera around the Upper West Side he had come to know while living in an apartment building on Riverside Drive. He eventually decided against appearing in the film, instead providing Blackwood with recommended locations and writing the text he then read as the film’s commentary. In this he praises the activism and the diversity of the “slum” he would, in Anniveraries, liken to a mobile jellyfish slithering about among the brownstones. He remains silent when Blackwood takes his camera into the transvestite world.

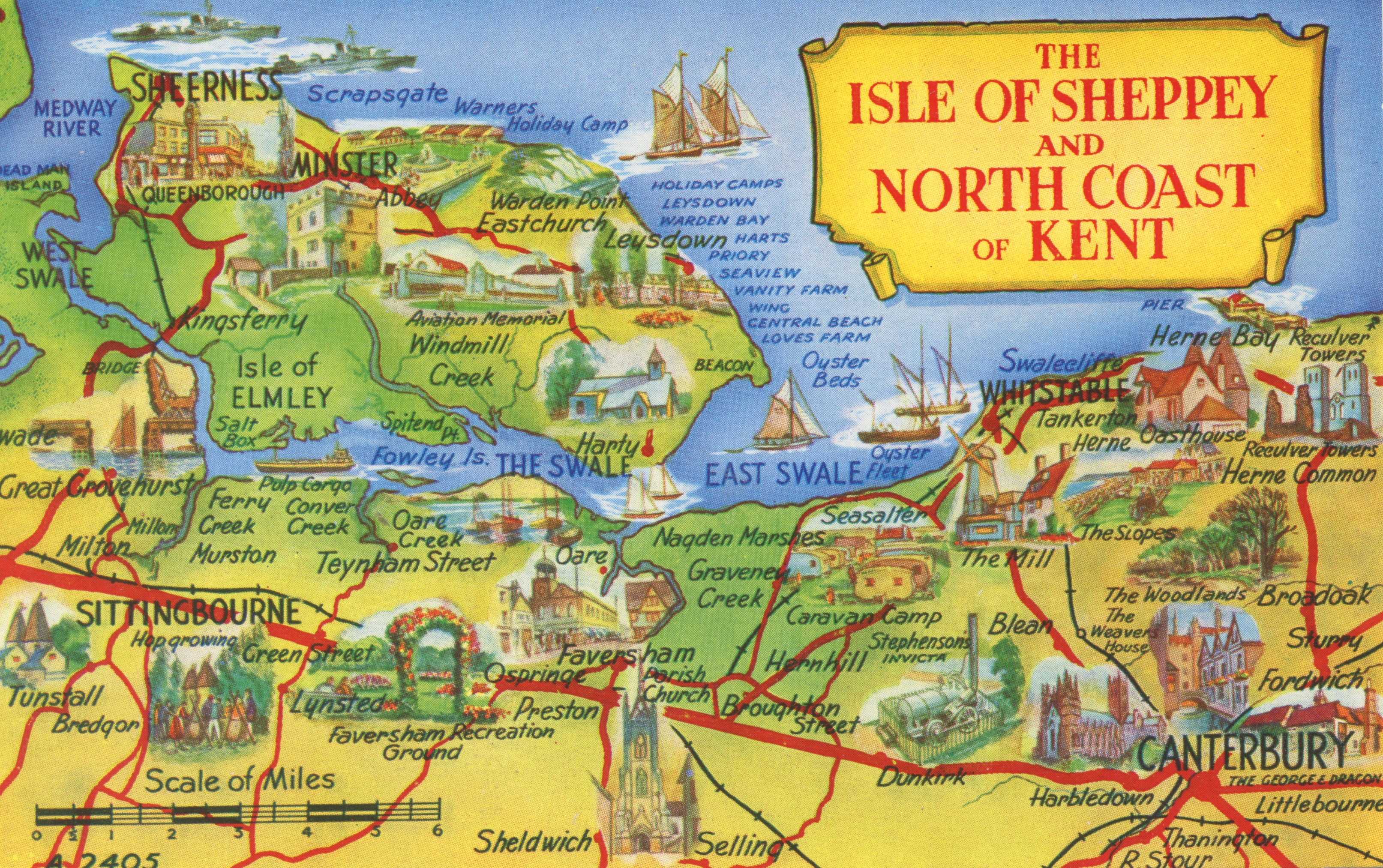

The Island

“I am reliably informed about a place where it seems to be no coincidence that a cul-de-sac in this country is not called that, or a dead-end street, but a blind alley. That would already be something”

— UJ, letter to Max Frisch, 4 August 1974

“The chalky, swampy fields on the island are really not at all Garden of England (if indeed any tourist can stand this smug catchphrase any longer than from Dover to Canterbury)”

Not always a lark:

cement on Sheppey

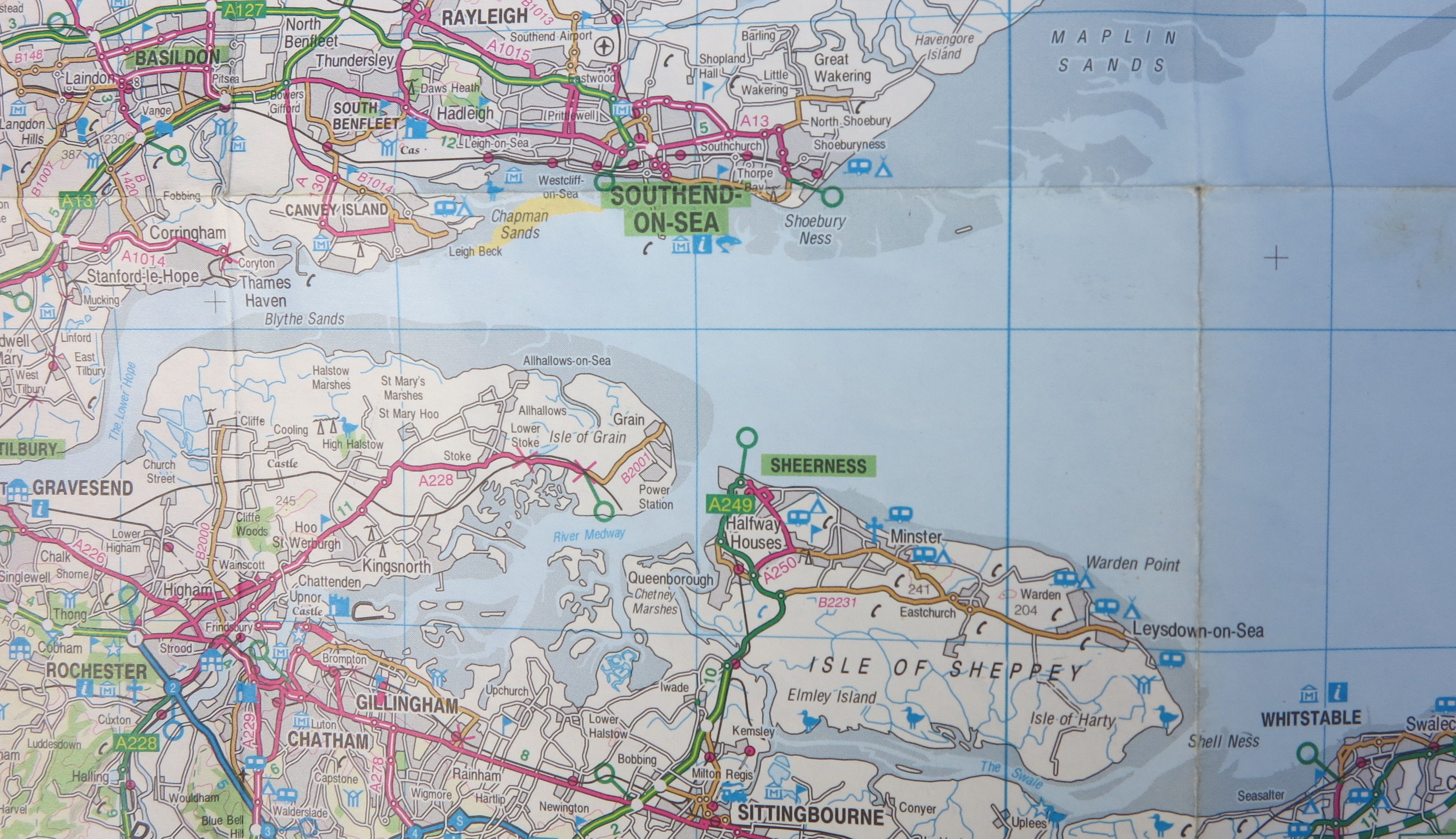

It lies on the eastern shore of the Medway, where this no longer naval river flows into the outer reaches of the Thames Estuary.

On its western side, it emerges from the water, in a marshy and noncommittal kind of way, not far from a bone-strewn mudbank called “Dead Man’s Island”.

To the south, once you get past the landfill site at Ladies Hole Point, the island is dominated by marshes and separated from the mainland by a tidal strait known as the Swale.

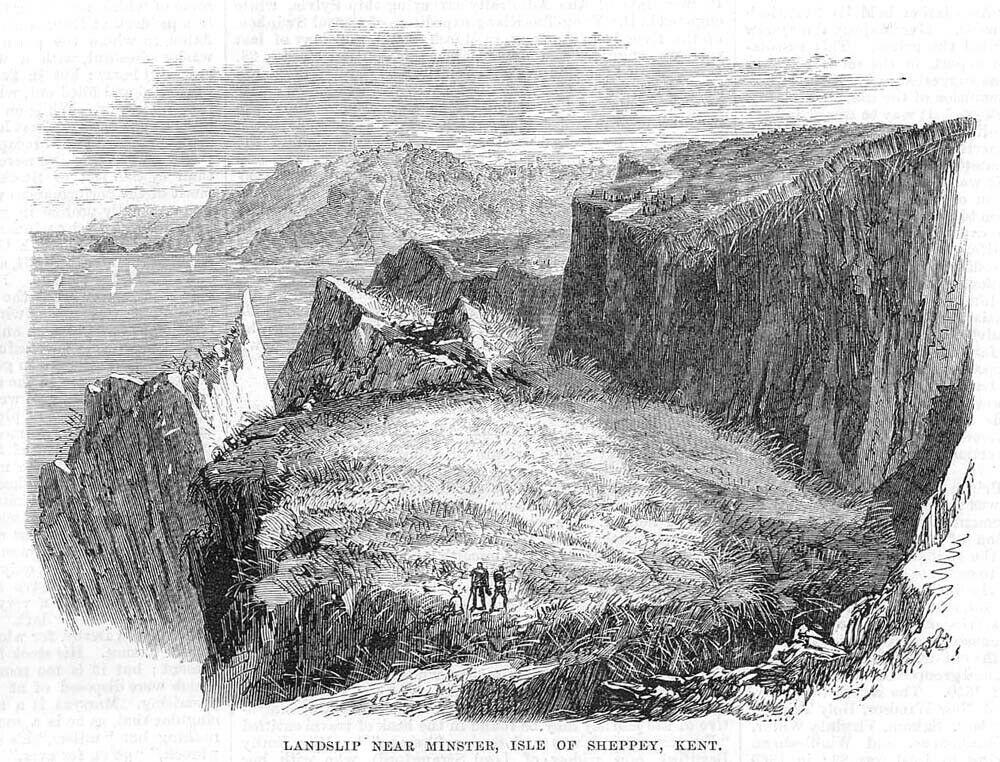

The northern shore is formed by a ridge of London Clay, which emerges near Sheerness-on-Sea and rises as it proceeds towards the eastern shore of the island, reach§ing its highest point of some seventy-six metres above sea level at Minster, a village at the early Christian site where St Sexburga, widow of the Anglo-Saxon King Eorcenberht of Kent, established a convent in 664 AD.

Such basic facts must be allowed, and yet the “Isle of Sheep”, as Sheppey’s originally Saxon name “Sceapig” describes it, remains variously suggestive in its separation from the mainland.

Not just an island, it is also a strange oscillation, a place where paradise keeps collapsing into the bleakest kind of slum.

“Having bad weather here,” postcard sent by J. Short to Mrs. Schofield in Portsmouth, 5 September 1913. This pub grotto, was assembled from a salvaged ship, said to have run aground loaded with barrels that turned out, disappointingly for some, to be filled with Portland cement.

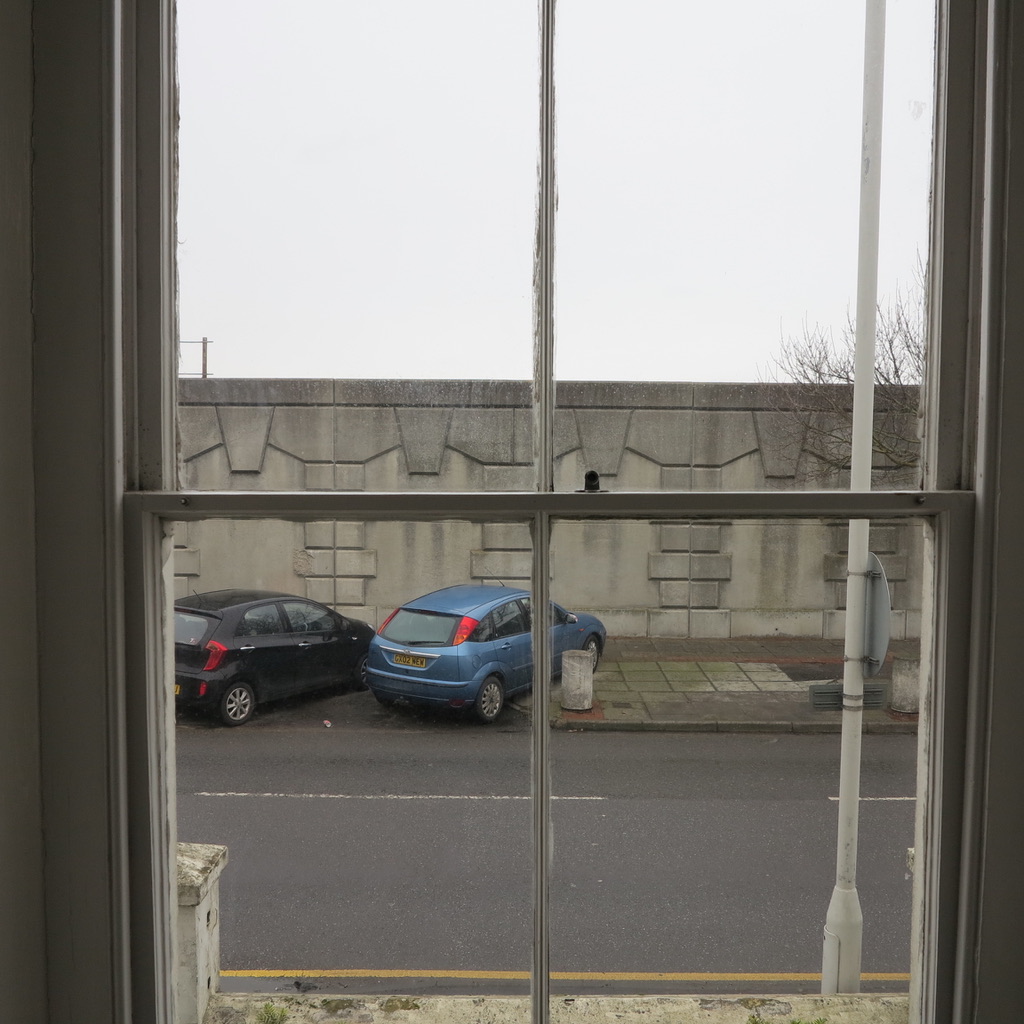

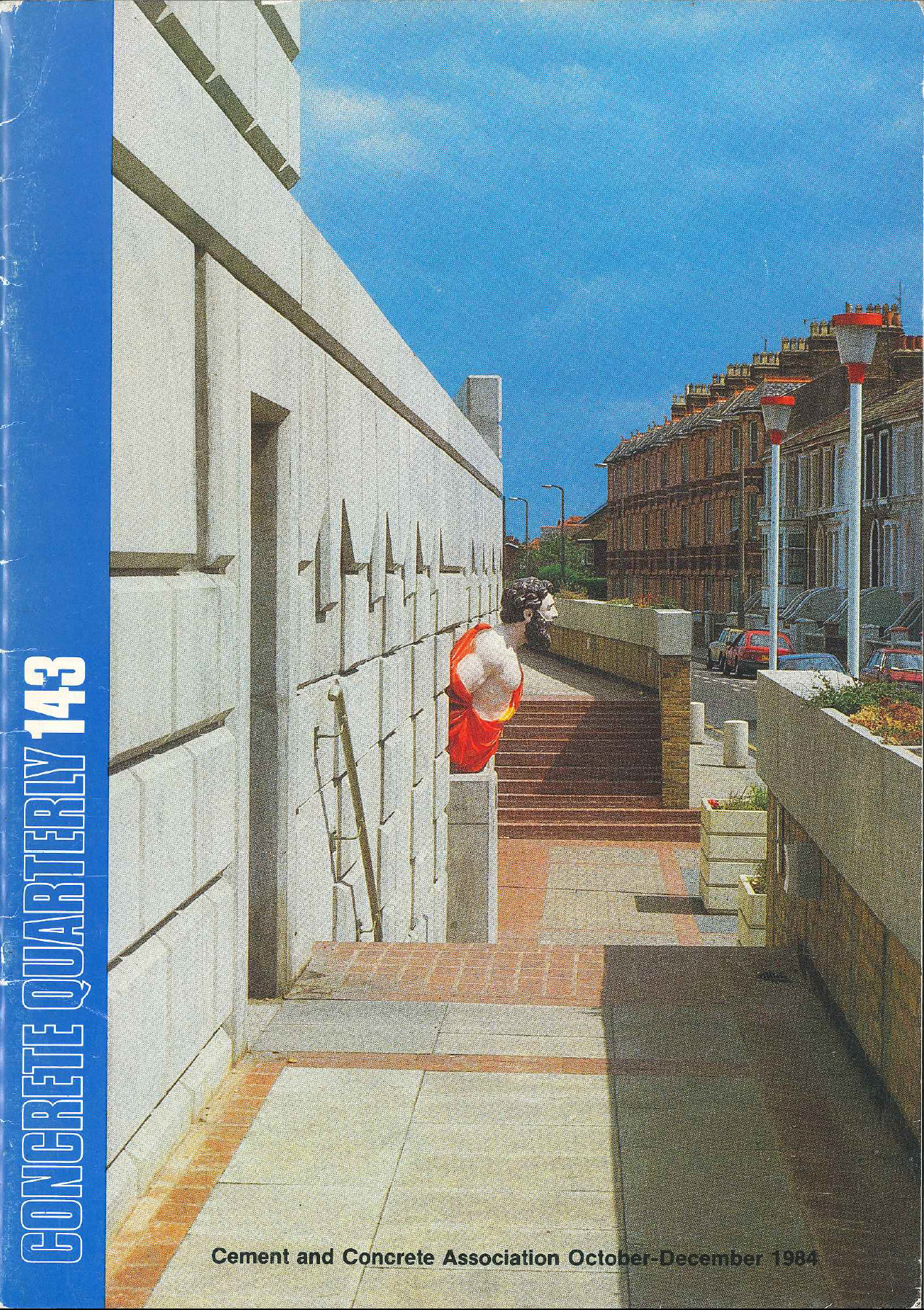

“Rusticated” sea wall, designed by Garnham Wright Associates and built along Marine Parade in 1983-4.

“Call it England or call it Sheppey, the island looks tiny on conventional maps: little more than a mudbank about eight miles across at its broadest point, and eleven in length. Those, however, are not the only dimensions that matter. While writing this book, I have learned to sympathise with the man from Gillingham, eight or so miles upstream along the Medway, who decided — a full six years before the Brexit referendum of 2016 — to buy himself a small motorboat via the internet and put to sea with the aim of navigating his way around Great Britain...

After studying a road atlas, he concluded that he only had to keep the land on his right-hand side in order to end the first stretch of his journey at Southampton. Having proceeded on this assumption for a day and a half, he ran out of fuel and found nhimself stuck in the mud near some tidal marshes. The lifeboat that came to rescue this slow voyager from his predicament guided him to the quayside at Queenborough where an officer of the coastguard service briskly informed him that he had all the time been circling the Isle of Sheppey: ‘He had no idea of the magnitude of the journey he was undertaking”’

Since this unidentified Englishman — he was, as I recall, rudely dismissed as a “dopey sailor” by the island’s newspaper — insisted on resuming his journey once refuelled, we may assume that he too had by then seen enough to know not just that small can be large, but also that life isn’t necessarily at its richest when it is predictable or easy.” (Sea View, pp, 8-9)

Sheppey, more or less West to East

“His address was Sheppey”

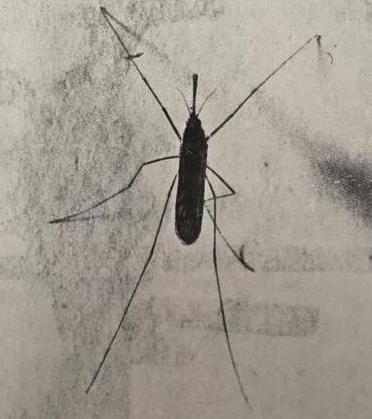

Anopheles maculipennis mosquito, photographed on a bedroom wall in Kent, 1918. this marsh-dwelling mosquito was a carrier of indigenous malaria, known as “marsh fever” and “ague” before it was scientifically identified by Sir Ronald Ross in India ain 1897. The infestations on Sheppey were particularly bad. At the beginning of the eighteenth century, Sheerness was described as “the most fever-ridden place in the whole of England.” In the mid-nineteenth century, there was much concern about the impact of this pestilence on the fighting strength of the navy at Sheerness (hence the towen’s heroic preoccupation with drainage at this time). The problem had long kept wealthy landowners and farmers from living on the island (many of the marshlands were run by “lookers” who had no choice but to lieve below the “contour of death”). I The affliction also recurred in the. twentieth century - not least after the First EWorld War, when the island’s mosquitoes were reinfected by soldiers returning from overseas (Sea View, 205-7)

Anopheles maculipennis mosquito, photographed on a bedroom wall in Kent, 1918. this marsh-dwelling mosquito was a carrier of indigenous malaria, known as “marsh fever” and “ague” before it was scientifically identified by Sir Ronald Ross in India ain 1897. The infestations on Sheppey were particularly bad. At the beginning of the eighteenth century, Sheerness was described as “the most fever-ridden place in the whole of England.” In the mid-nineteenth century, there was much concern about the impact of this pestilence on the fighting strength of the navy at Sheerness (hence the towen’s heroic preoccupation with drainage at this time). The problem had long kept wealthy landowners and farmers from living on the island (many of the marshlands were run by “lookers” who had no choice but to lieve below the “contour of death”). I The affliction also recurred in the. twentieth century - not least after the First EWorld War, when the island’s mosquitoes were reinfected by soldiers returning from overseas (Sea View, 205-7)

“Island” — the Requiem

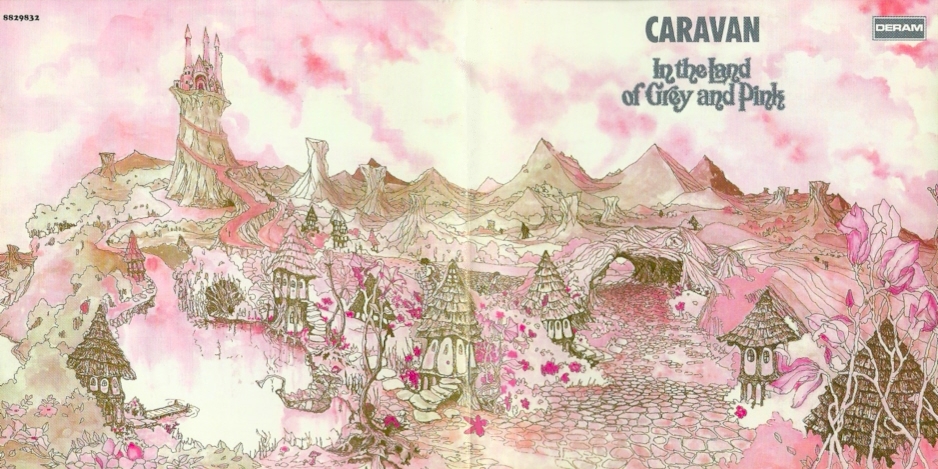

In 1973/4, a thoughtful man named Dave used to come to 5 St Radigund Street, Canterbury, where I was then living as a student. He was a friend of another resident, the singer Barbara Gaskin, and we sometimes referred to him as “Ziggy” in honour of the stardust trailing behind him. Dave, was Dave Sinclair, former keyboardist with Matching Mole and Caravan, whose album

In 1973/4, a thoughtful man named Dave used to come to 5 St Radigund Street, Canterbury, where I was then living as a student. He was a friend of another resident, the singer Barbara Gaskin, and we sometimes referred to him as “Ziggy” in honour of the stardust trailing behind him. Dave, was Dave Sinclair, former keyboardist with Matching Mole and Caravan, whose album

“In the Land of Grey and Pink” (1971) had taken its title from sunsets over the Isle of Sheppey. Band members had watched these fractal explosions of colour from the marshland village of Graveney, where they’d found a hall in which to rehearse.

Dave spent many years, including those in which the memory of “prog rock” was blasted into the past by the later punk sensibility, running a piano restoration business in Herne Bay. He moved to Japan in 2005 where he now lives on Yuge island, Kamijima. Perhaps some fleeting memory of that view over Sheppey informs his more recent song “Island” (2011), a simple elegy to the hopes of a lost era, here sung by Barbara Gaskin. Johnson, of course, knew nothing of this. Yet he was curious and, when living in America in the Sixties, he once asked the young Richard Hamburger to copy him a cassette of his favourite music.

Dave spent many years, including those in which the memory of “prog rock” was blasted into the past by the later punk sensibility, running a piano restoration business in Herne Bay. He moved to Japan in 2005 where he now lives on Yuge island, Kamijima. Perhaps some fleeting memory of that view over Sheppey informs his more recent song “Island” (2011), a simple elegy to the hopes of a lost era, here sung by Barbara Gaskin. Johnson, of course, knew nothing of this. Yet he was curious and, when living in America in the Sixties, he once asked the young Richard Hamburger to copy him a cassette of his favourite music.

Island Birds

Brent geese at Shellbeach

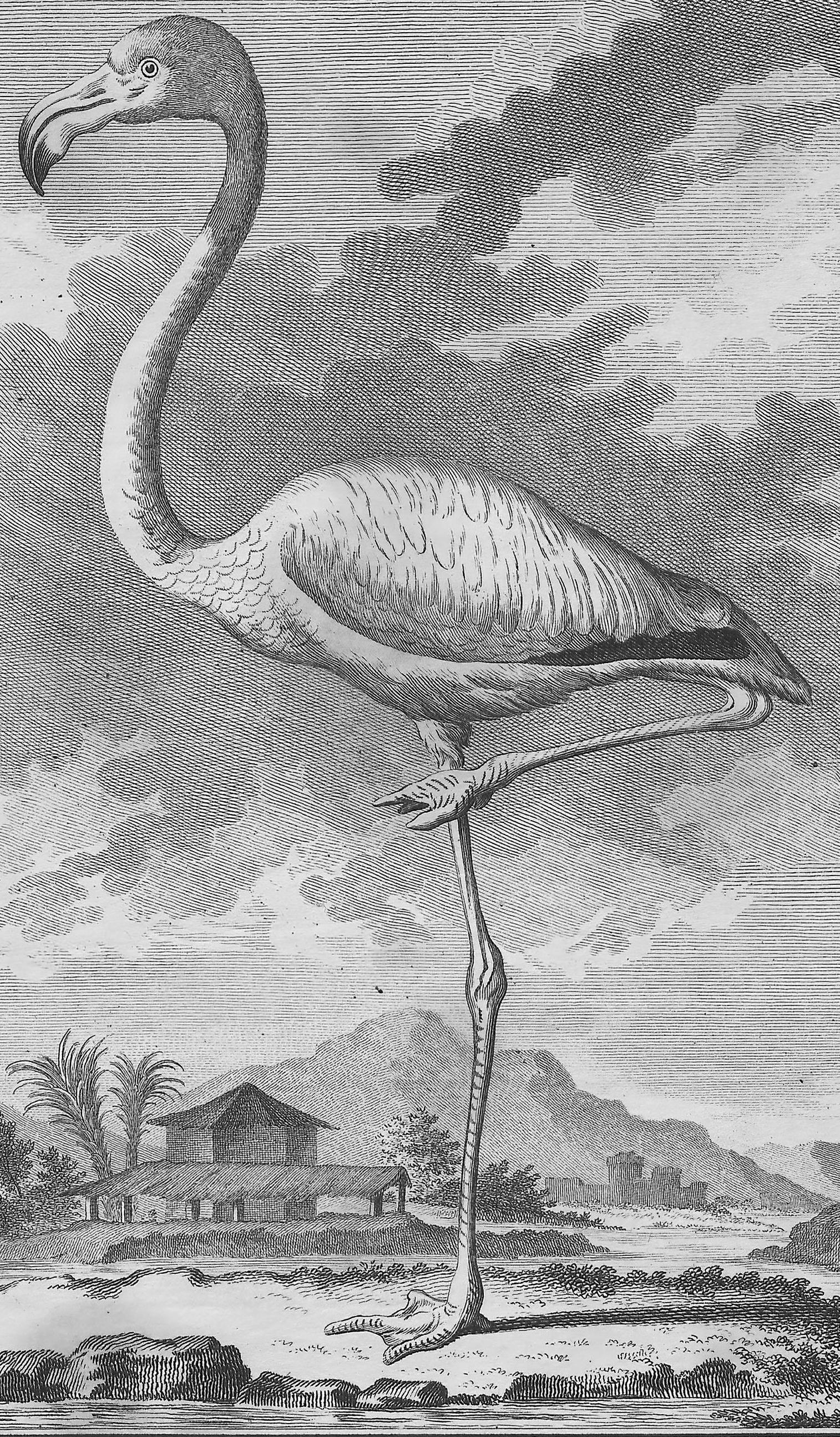

A female flamingo (Phoenicopterus antiquorum) tried its luck on the Sheppey marshes in the summer of 1873. The erratic visitor was shot by a labourer named Heathfield, who tracked it down to Sharfleet Creek on the Swale. Sheppey’s firebird was claimed as a first for the country. As such, it was eviscerated and stuffed by a Mr. George Young of Sittingbourne on the mainland, and sold to a man named Dene from further inland at Tonbridge. The new owner was to receive a disappointing lesson from the superintendent of London Zoo, who revealed that the unfortunate creature was actually an escapee from his collection at Regent’s Park.

“He

walked to the door and threw it open. The sea, the sea. Grey and brown. It

would rain soon. It was bleak out, bleaker, if possible, than it had ever

seemed before. What a view. Luke grimaced. What a bloody landscape!”

— Nicola Barker, Wide

Open (1998)

Sheppey: “Rural slum”

and/or “Moral Utopia”?

Johnson’s first German visitors were by no means impressed by the remote, industrial, working class island on which he had chosen to live.

“As [Siegfried] Kunert recorded in his An English Daybook the seats inside British Rail’s shabby conveyance were a poor advertisement for the attractions of “Sheerness-on-Sea.” Their headrests were ‘enormously patinated’ — so much so that one was stuck with white tufts of hair as if an old man had struggled to ‘tear himself from his seat on arrival.’”(Sea View, p. 195)

“Every time I arrived and left, my feeling was the same: how can one live here, and how can one write here, in this run-down town, with little or no possibility of preserving what makes the outer life worth living?”

— Siegfried Unseld, Johnson’s editor and publisher at Suhrkamp, Frankfurt (Sea View, p. 195)

Helga Michie, the twin sister of the Austrian writer Ilse Aichinger who had arrived in London on a Kindertransport in 1939, understood the situation differently:

“He likes it there. It reminds him of home... It’s the landscape — sea, sand, marsh.”

Helga Michie, the twin sister of the Austrian writer Ilse Aichinger who had arrived in London on a Kindertransport in 1939, understood the situation differently:

(Sea View, p. 197)

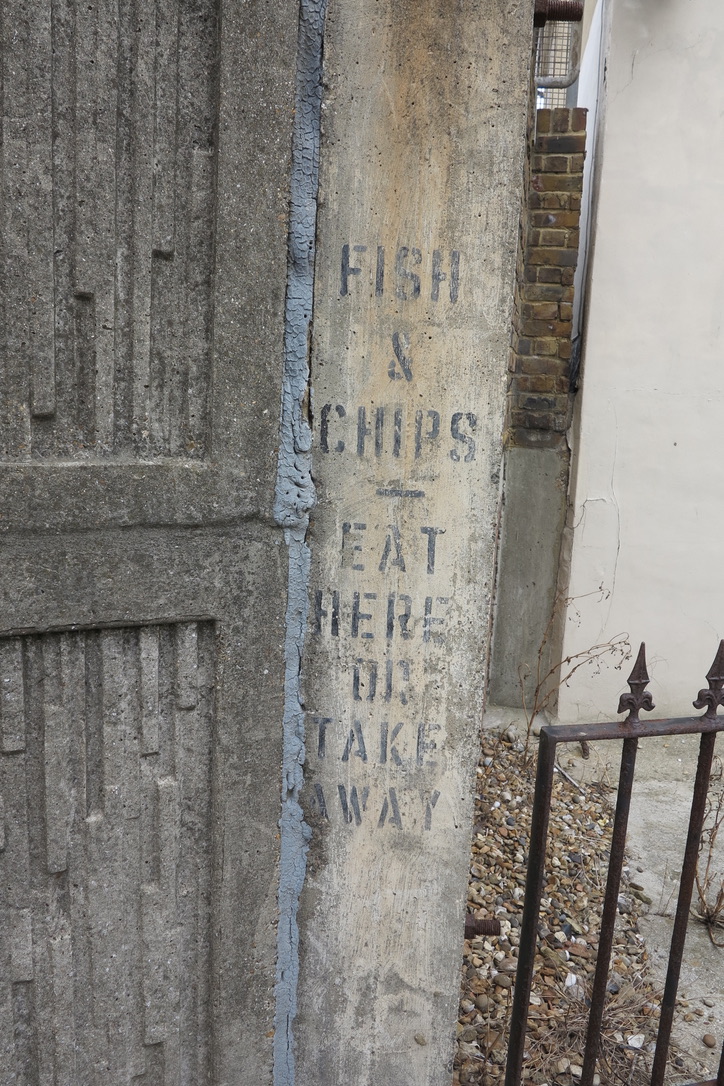

For centuries, Sheerness had survived and sometimes prospered as a military town. It was created to meet the requirements both of the Admiralty dockyard, first laid out by Samuel Pepys and others in 1665, and of the associated army garrison installed next to it on the marshy point (the “Ness”) overlooking the mouth of the Medway and the submerged sandbank that would become the naval anchorage known as the Nore. The people of the town that grew up around the dockyard had long feared their reliance on the Admiralty, and steps were also taken to establish the place as “Sheerness-on-Sea”, a resort for visiting Londoners. As such, it would always struggle to match rivals like Margate, where the golden sands bore no disillusioning resemblance to shingle and excursionists disembarking from the steamer that had brought them from London didn’t have to make their way through the disorderly military slum named Blue Town (”Whitechapel-on-Sea”) in order to get from the pier to the beach.

Johnson knew about the poverty and deprivation on Sheppey, but he didn’t at all mind the absence of the shinier trappings of western life - the rampant consumerism, the displays of opulence, the bourgeois habits of thought that had never made their way over the Kingsferry Bridge from the so-called “Garden of England”. A longastanding scourge of the hypocrisy of the liberal middle classes, he aligned himself with the island’s unemployed and came to appreciate the not always law-abiding solidarity of the people as they got by despite the unhelpful attentions (or neglect) of the state. He told one East German friend that he had discovered a “moral utopia” in this English backwater, where many of his friends saw only misery, abandonment and bleak deprivation.

The Past

Minster Abbey and its afterlife

![]()

Stephen Fry once suggested that the people who lived in the past were really just “us with different clothes on”. Looking at this ancient Green Man in the Church of Mary and St Sexburga, Minster, we may doubt it ...

Sacked by Vikings and dissolved by Henry VIII but the church and gatehouse of St. Sexburga’s abbey are still standing on the island’s highest ground at Minster-on-Sea:

Minster Abbey, from top rear bedroom of Uwe Johnson’s House at 26 Marine Parade, Sheerness...

“I shall be glad when I get a job sooner or later”. Postcard with “Birdseye View of Minster”, postmarked 3 June 1909.

Women’s Suffrage: a modern cause lands at Minster, September 1909

![]()

“Here on a grassy triangle outside the churchyard, a group of about fifty villagers and visitors assembled on Wednesday 11th, to hear the Hon. Mrs. Bertrand Russell [the American reformer, Alyse Pearsall Smith] speak on Women’s Suffrage . . . It was, as far as I know, the first Women’s Suffrage meeting ever held in Sheppey island, and no more appropriate spot could have been chosen for the occasion. Among the famous Saxon women of Kent, beginning with the Christian Queen Bertha, two of the most distirnguished belonged to Sheppey. Sexburga, queen and saint, to whom Minster Abbey Church is dedicated, was daughter to Annas, king of the East Anglians, wife to Ercombert, King of Kent, and mother to two succeeding Kings of Kent. She founded and ruled over a monastery for Benedictine nuns on the hill at Minster. In later life she became Abbess of Ely, and was succeeded in Minster by her daughter Princess Ermenilda, who in her turn became Abbes of Ely” Kate Ralegh in Women’s Franchise, 2 September 1909 (Sea View, pp. 174-80).![]()

Long Lost Family: a Successful Week on the Isle of Sheppey, June 1938

“A Wholesale Imposter.—In the beginning of last week, a man called upon Mr. and Mrs. Griffin, at the preventive station, Queenborough, representing himself as a relation; and was, in consequence, liberally entertained by them. On Wednesday, he discovered another relation among the military in Sheerness garrison; and a subscription was made for him among the soldiers, amounting to 7s. 6d. Afterwards, he found a cousin, a poor man, in Blue Town, with whom he resided a day. On the same night, about ten o’clock, he found another cousin, a poor man (Mr. Hayse), who was going to bed when he arrived; but upon the arrival of a cousin, they cooked a supper, and entertained him to the best of their ability; and afterwards gave up to him their own bed. On Saturday, he found a cousin Adams, with whom he partook a greedy meal of nearly two pounds of meat, and a pot of porter, &c. Here he carried his deceptions as far as to kiss Mrs. Adams, who shed copious tears upon the occasion of the discovery of a relative. The same day, he found cousin Curry, with whom he partook of ham &c., for tea, and obtained 2s 3d from Mrs C., to pay the pier dues for his luggage; having nothing, as he said, but doubloons by him, which he could not get changed. The same night, he gave a second visit to Queenborough, and found out cousin Morris; but obtained nothing from him. He appeared, wherever he went, to be quite at home, by looking into cupboards, and dealing out apples &c. from them to the children. The imposter resided in Sheppey altogether a week; after which, he appears to have found out the mother of a New South Wales convict, near Sittingbourne, from whom he pretended to have brought a letter. He next introduced himself to the clerk of a brewery at Chatham, from whom he obtained 7 s. This is the last place we heard of him. He is about 5ft. 6in. in height—60 years of age. He had on a brown coat, grey trowsers and long waistcoat—the whole considerably worse for wear.”

—Kentish Mercury, 9 June 1838.

A Bar Goes Under

from West Berlin to East End Lane

(an indication of method

and a story

that didn’t make it into Chapter 13)

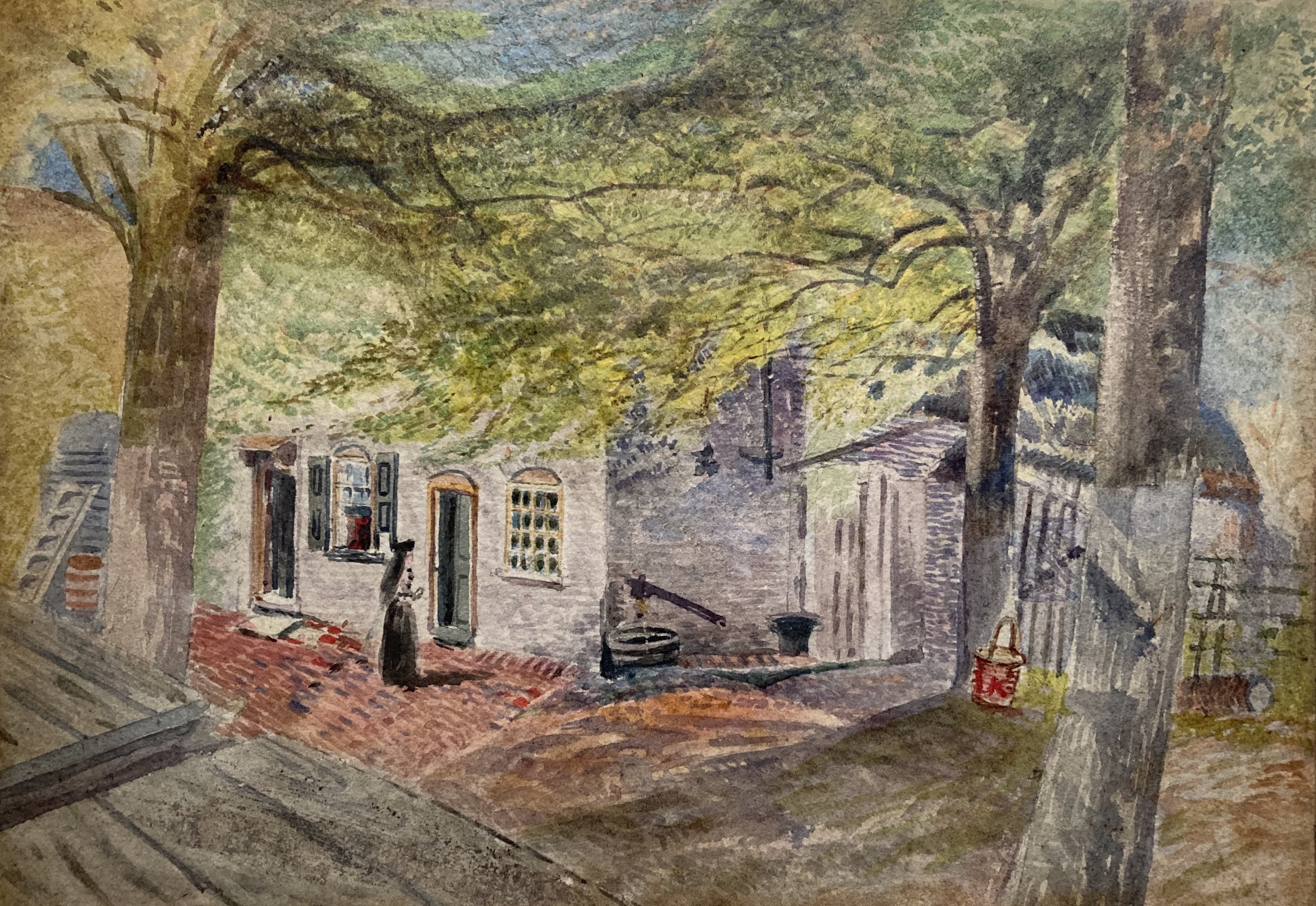

In mid-Victorian times, the Royal Oak was one of the more remote destinations available to visitors on the Isle of Sheppey. Search for it via the British Newspaper Archive, and it makes its earliest appearance on 7th June 1859, when it was offered for sale in the South Eastern Gazette. Described as “a desirable inn” situated in “the most beautiful part of the Isle of Sheppey”, it was equipped with “about Three Acres of Land, consisting principally of Plantation of Fruit, Pleasure, and Garden Ground”. Perched at the end of the world, the Royal Oak was, without question, a place of some romance. Known as the haunt of smugglers as well as of the more energetic and/or secretive summer excursionists, it also played a significant role in the island’s largely forgotten political history.

On Saturday 7 June 1873, the Sheerness Times and General Advertiser, informed its readers that 200 of the island’s agricultural labourers had made their way to the Royal Oak from all parts of the island to attend a meeting the previous Saturday evening. The assembly, which was part of that decade’s nation-wide “Revolt of the Fields”, had been called so that Mr. Harry Howard of the Kent Agricultural Labourers’ Union could propose the creation of a Sheppey branch of this fast-growing friendly society. The union had been founded in Maidstone only a year previously and was under the leadership of Alfred Simmons, a journalist editor of the Kent Messenger, who once attributed his sympathy with the county’s agricultural labourers to his own experience of growing up in poverty as one of five children of a mother widowed in her early thirties.

Howard may still have been wearing the “agricultural” boots and leggings for which he had been mocked in the Maidstone Journal’s sneering report of the union’s recent fundraising meeting in Gravesend. Yet he knew how to present a reasoned case even while ridiculing the objections farming interests had tried to plant in their workers’ minds. It was, Howard stated, the general saying in a village that when men joined the union they did so in order to strike. “There was not a greater fallacy than this,” because a union “was merely a combination of men to benefit themselves, so that there could not be very much wrong with it.” Unions used the strike only as last resort, and this one hoped to find other ways of saving its members from the answer that customarily awaited labourers who dared express any grievances.

“If you don’t like it, go!” That was the reply the demanding, or just pleading, labourer could expect from his employer. And those who were forced to “go” had no chance of getting employment from another farmer in the parish. So the aggrieved worker had to leave the area, knowing there would be plenty of other men to take up the work at starvation wages. Once the new organisation became “general”, Howard promised, it would have the leverage to put an end to this misery. The Kent Agricultural Labourers’ Union was, so Howard encouraged the more timorous onlookers to understand, one of the last unions to form: even the Church of England’s curates had recently created such an association to save themselves from being “ground down to the lowest by the big wigs of that Church”.

After Howard’s rousing speech, the meeting adjourned to the pub, where a Sheppey branch of the Kent Agricultural Labourers’ Union was duly formed with a membership of 70 men. Two years later, its members were coming to terms with the island farmers’ reaction to their unwelcome exercise in collective self-defence. In April 1875 one who knew better than to reveal his identity except as “a farm labourer”, wrote to the Sheerness Times to let readers know “how those who are uniting to attain a reasonable day’s pay are treated by the “Amalgamated Club” of the farmers of this island.

On Sheppey as elsewhere in the county, the labourers had been “locked out” because they were demanding a working day of 10 hours. A young man who had been elected branch secretary of the Kent Agricultural Labourer’s Union, was immediately discharged from a farm near “Court Tree” and also dismissed by the church wardens from his long-established additional employment as “organ blower” at the church in the agricultural village of Eastchurch. Two years earlier, the union’s founder and Honorary Secretary Alfred Simmons had told a meeting in Lamberhurst that the “unmanly, unkind, unchristianlike” behaviour of the farmers was “unworthy of Englishmen.” (Kentish Gazette, 17 June 1873, p. 3) This unnamed Sheppey labourer now repeated that charge, urging “those who deprecate the Unenglish proceedings of the farmers of Sheppey,” to contribute their “mite” towards the welfare of those injured by the “lock out”. He also noted that the branch lodge continued to hold its meetings at the Royal Oak in East End Lane.

As the red bucket in the unknown watercolourist’s picture may suggest, The Royal Oak was among the remote buildings on Sheppey’s east coast that proved remarkably prone to fire. It was, however, a different threat that eventually put an end to the Royal Oak. On this coast, the idea of “going under” is all too literal – fields, houses, churches, coastguard stations, pillboxes have been doing it for centuries. The cliffs are of soft London clay, and it has been estimated that miles of land may have dissolved into the rising sea since Roman times. In “volcano land”, as this unstable coast was dubbed by the Illustrated London News after a fall in January 1909, the end comes not as a crashing fall of rocks, but as a slumping movement of mud and clay in which undermined areas “glide” down, often strangely intact, towards the water.

A typical Sheppey landslip had occurred in 1809, when a great clod of land measuring 500ft by 150 ft “slid gradually down to the valley called Busbyhole”. It took with it parts of a dwellinghouse, a cow-house and several outbuildings’ but the descent was so gradual and gentle, that the corn planted on the land could still be “harvested in a good condition the following autumn”.

Another of these falls occurred in June 1870. As the Sheerness Times reported on the 25th, this one had been seen by two officers who, having just walked over the fallen acre, announced the descent to have been “a grand sight”. The pleasure gardens sold as part of the Royal Oak Inn had recently been diminished too – “large slips of land have also taken place at the Royal Oak, East-End-Lane, during the past few years, reducing the lawn, which was of considerable size, to the insignificant area it now occupies.”

Although the surrounding land and garden kept collapsing around it, the Royal Oak survived until the 1950s, when it was finally cleared before it joined its ancient orchard and bowling green in “going under”. As for the Kent Agricultural Labourers Union, by the 1880s, the much maligned Albert Simmons had connected its cause with franchise reform, standing as a parliamentary candidate for William Gladstone’s Liberal Party and calling the labourers of Kent to join the Liberals against the “scornful curl of the lip” with which Tories had always met their demands for improvement (Thanet Advertiser 27 June 1885, p.4 ).

Simmons may be less remembered than Joseph Arch of Warwickshire, but the Kent Agricultural Labourers Union was one of the most successful of the associations that formed during the Revolt of the Fields. This may be attributed to its use of festivals and journalism as well as its strike and sickness funds. Yet it was also distinguished by its commitment to assisted emigration, a cause that earlier defenders of the English rural community such as William Cobbett had opposed as a wholly unnecessary displacement spuriously justified by appeals to Malthus’s theory of the surplus population. For Simmons, on the contrary, emigration was another weapon in the battle against the Tory farmers.

Speaking to a crowd of about 1000 in Canterbury in July 1872, Simmons disputed the frequently trotted out allegation that the union had been got up by “paid agitators” determined to bring on a strike. Its policy, he explained, was actually moderate and gradual. The first step was to request an increase in wages, and then to seek independent arbitration if this was refused. The third measure, which was placed before the fourth and final option of calling a strike, was to enable “such men as desired” to migrate or emigrate “from Kent to better places” (Maryport Observer, 20 March 1874, p,. 2.) Various destinations were available, but the union appears to have favoured sending its emigrating families “down under” to South Australia and New Zealand. It helped 234 families embarked for South Australia near the end of 1873. 400 had gone by the end of the year, when a concerned farmer from Waltham ventured the hope that a good half of them would soon enough be begging to exchange “the aguish forest of New Zealand, the blinding sands of Australia, or the wild prairies of North America for the hop gardens of Kent.” (Kentish Gazette 16 December 1873). In 1879, Simmons countered another farmers’ lock-out by filling a steamship made available to him by the Agent-General of New Zealand, and himself joining the emigrating labourers on their voyage. Since many of the departing labourers had worked in Kent’s hop fields, he took a selection of hop plants so that they might renew their activities once landed.

As Simmons intended, this encouragement of emigration helped increase pressure on farmers, especially at busy times of year when their harvest depended on the easy availability of workers. It’s effectiveness may be measured by various furious reports in the county press. It would be said that Simmons and the other “mountebanks” at the head of the union were making a killing from the commission they secured for everyone they signed up for free passage to the far side of the Empire. The county’s Tory papers also opened their pages to stories about the bitter disappointment of emigrants who disembarked in places that were anything but the “land of milk and honey” they had been promised. Regrets were keenly anticipated among those Simmons had sent to New Zealand and South Australia, but the commentators had to make do with those of the agricultural labourers who had been “induced by philanthropists” to embark for Brazil in May 1872, and soon found themselves doing the work of slaves: “We live together like pigs… We would not have come here for all the world had we known” (Kentish Gazette, 24 December 1874). Nobody could justifiably stick the blame for that particular passage on Simmons, but the accusation was generalised nonetheless.

A rotation like this had long been underway in the agricultural economy of Sheppey, with farm labourers emigrating to America, often helped by children who had gone before them, and their departure being noted in newspapers in Ireland (the Sligo Champion published such a notice on 3 November 1851), whence “itinerant” labourers would make their way to the island to take up available work at harvest time. It was in a clash between Irish and English labourers at Eastchurch during the harvest of 1837 that the insulting word “pikey” is said to have entered the English language (Sea View, pp.107-8).

Of the agricultural labourers who didn’t ship out for the “New World”, we might now think more generously about Benjamin Bunk, an elderly and besmocked labourer who turned up at one of the island’s first Suffragist meetings in August 1909. One of the holidaying speakers, the American Alys Pearsall Smith (aka Mrs. Bertrand Russell), records that Mr. Bunk proved an awkward presence before going off to get himself another glass of beer. Overall, though, she found herself facing a serious and attentive audience at that meeting in Eastchurch, singling out a roughly clad young labourer, who stood rapt and immovable throughout the astonishing event, and dropped several coins into the collection pail at the close (Sea View, pp. 176-7).

A politics that once counted: two blasts from the rural class struggle in late Victorian Kent

“This meeting of Kent and Sussex labourers and representatives of Liberal Associations of Kent and East Sussex, remembering the promise that the present Parliament should not be dissolved until the household suffrage had been granted to the counties, tenders its grateful thanks to Mr. Gladstone and the Liberal party for the consistency with which they have fulfilled that promise to the people.”

From the time of my boyhood I have been, as I hope and believe, a consistent follower of the man whom I believe to have been the best friend that the working classes of the country ever had (a voice: Gladstone), and I assure you it sends a thrill of grateful pleasure through me to be selected to move this resolution of thanks to our grand old leader, Mr. Gladstone ((Loud cheers.) The speaker then recounted the long and great struggle the labourers had had to obtain their rights, and pointed out to his hearers who it was that had always opposed them. His experience had been that when they asked a Conservative member of Parliament to support that measure they had been met with the scornful curl of the lip. “We have been mocked and laughed at, and I tell you, and I tell you truthfully, that you do not owe the smallest amount of thanks to the Tory party for your votes. (Cheers.) I have been asked by some labourers to describe if I could what was the difference between a Conservative and a Liberal, and to do so I will tell you this. The Conservatives always have obstructed and attempted to cripple the reforms demanded by the people. The Liberals have always initiated and advocated and agitated these reforms in the teeth of the Tory party, and they have been victorious (Cheers.) This is the difference between the Liberal and Tory. The Tory obstructs you and keeps you down. The Liberal helps you to get up, rise; and to-day I, as one whom I believe you will trust, tell you this that so far as I am concerned no uncertain sound shall proceed from me on this question (Cheers.) . . . I venture solemnly, seriously to warn you against being duped, hoodwinked by these atrocious statements of our opponents, and I would like you to ask them, if the Tory party have not opposed you, who has? (Cheers.) How is it that the franchise was not introduced when you first asked for it 13 years ago? Where has the opposition come from? Why as a matter of fact and certainty it has come from the usual quarter from which opposition to the people always has and always will come, from the Tory party. (Hear, hear). Although perhaps there may be individual men stupid enough to allow themselves to be hoodwinked (hear, hear), let me beseech of the mass of you to stand, firmly and honourable by the side of those of us who have led you to victory…”

“So far as Kent is concerned we believe there is now a real “reunion of hearts” between the three main elements into which the agricultural community is divided. A few years since it was not so. Then the labourers regarded their masters and their landlords, to say nothing about the parson, as their natural enemies. That feeling was the outcome of the pernicious teachings of Mr. Alfred Simmons and others connected with the Agricultural Labourers’ Union. But we all know how that union has dwindled into a state of impotency, after doing an infinitude of mischief in breaking up those kindly relations which had for many years existed between the Kentish farmers and their men. We have good warrant for saying that no one now regrets that more than the labourers themselves; and that in future they will rather treat their natural leaders — the landlords and the tenant farmers — than put any reliance in such mountebanks as Simmons, Steadman, and others, who only have their own selfish ends to served. Who that remembers that first meeting in the Bell Rink, at Maidstone, some three-and-twenty years ago, when Simmons, Roots, and Co., with the aid of the Maidstone Telegraph, floated the Agricultural Labourers’ Union, can look back upon it with anything but disgust and execration? How many of our sturdy Kentish labourers — good, honest men and true — that were then and afterwards led into joining the union ever suspected that it had its origin in an emigration scheme, whereby its promoters were to put a handsome sum into their pockets for every man, woman and child they could send out of the country? That scheme was the death-knell of hundreds . . . Simmons was king, with a following of twenty thousand dupes, not one of whom derived any lasting benefit from their slavish adherence to their newfound saviour. Their hard earned money was squandered in gew-gaws, scarves, ribbons, stars, flags, and banners; Simmons and his satellites drew high salaries, and in the end they prosecuted him for misappropriating their funds.”

A house for Somerset Maugham’s

Cockney barber, “Sheppey”

“I wish now I’d gone down to the Isle of Sheppey when the doctor advised it. You wouldn’t ’ave thought of looking for me there.”

— “Sheppey”, who was played by John Gielgud in the first prodution, speaking to Death in Somerset Maugham’s last play, Sheppey: a Play in Three Acts, 1933

“I know the very ’ouse I’m going to buy when my ship comes home. Two acres of land. View of the sea. Just the place for me and my old woman.”

Sheerness

“On-Sea”

in all weathers

Under snow

D.H. Lawrence on Marine Parade’s

First Breakwater

D.H. Lawrence’s mother, Lydia Beardsall, grew up in Sheerness before 1870, when an accident in the dockyard wrecked her father’s health and forced the family, which had lived there since 1858, to leave in some penury. Lawrence would later describe her as a “superior soul”(by which he surely didn’t mean that she was a snob). He also used her as the model for Gertrude Morel in his novel Sons and Lovers (1913): sensitive and intelligent but married to a brutalised and drunken Nottingham miner and inclined, in the midst of this life of “dreary endurance”, to grieve for the girl who had “run so lightly on the breakwater at Sheerness ten years before”.

Sheerness from above

“Then, for the first time, I saw Sheerness from 10,000 feet up, a spit of land between the Medway and the Thames.”

— Uwe Johnson, 1978

See Johnson’s neighbourhood as a German visitor filmed it when he was still there in 1981.

The Johnsons’ House

Mutual Aid: scaling the Heights of Alma. A pub seen from the upstairs back window of 26 Marine Parade

Neighbour: Martin Aynscomb Harris,

the artist next door but one

![]()

“He drives a Jaguar, even if he uses it the way other people use apple carts” (UJ, Sea View, 346-66).

“He drives a Jaguar, even if he uses it the way other people use apple carts” (UJ, Sea View, 346-66).

![]()

Martin Aynscomb Harris, selected paintings exhibited against his father-in-law’s car, Rowland’s Castle, Hampshire, c. 1965 (both pictures shown with thanks to Louise & Emma Harris).

Martin Aynscomb Harris, selected paintings exhibited against his father-in-law’s car, Rowland’s Castle, Hampshire, c. 1965 (both pictures shown with thanks to Louise & Emma Harris).

Looking Through Glass

Lighthouse, Cap Arkona, Rügen

Günter Kunert once suggested that Uwe Johnson viewed the world through a “bell jar of strangeness”. Yet the glass behind which he isolated himself was surely the lens of an observatory too. When I put a question about Johnson’s essay “An Unfathomable Ship” to the German sociologist Renate Mayntz, who was a friend of the writer over many years, she described it as “very characteristic of [Johnson’s] way of looking at reality: incisive, cold, as objective as possible, a camera that catches all details and even the legacy, the history inscribed in the present... I think in his passionate search for descriptive exactness, for ‘truth’ without implied protest or some normative ‘message’, he was a true representative of Enlightenment. There are things you don’t have to say, you just need to show them.”

The Sea View Has Me Again, p. 589.

Johnson’s other Observatory

Johnson once told Le Monde that his years in the GDR had equipped him with an “irreplaceable method of interrogation and experimentation.” (Sea View, p. 36). Two local pubs, in particular, came to serve as the informal research institutes in which he applied this challenging mode of enquiry to the people of Sheerness. His chosen hostelries, The Sea View Hotel and the Napier Tavern, were both on Broadway, close to his house. According to Ronald Peel, publican at the Napier Tavern, Johnson always turned up at the same time in the evening, stepping into the saloon bar with a brief “Good Evening” — or “Good heavening!” as Johnson himself imagines them registering his pronunciation — and then taking his customary place on a high, wooden barstool with a seat upholstered in red synthetic leather of the type Tom Waits was in those days hymning as “Naugahyde”. He allegedly always wore the same distinctive garb too: a black peaked watchman’s cap, a black leather jacket, black trousers, black leather boots, and sometimes a thin black leather tie — the same gear, in other words, that had shocked the poet and translator, Michael Hamburger, who had been astonished to find this highly regarded and sensitive writer going about in the garb of a Hell’s Angel or skinhead. (Sea View, p. 392)

Johnson once told Le Monde that his years in the GDR had equipped him with an “irreplaceable method of interrogation and experimentation.” (Sea View, p. 36). Two local pubs, in particular, came to serve as the informal research institutes in which he applied this challenging mode of enquiry to the people of Sheerness. His chosen hostelries, The Sea View Hotel and the Napier Tavern, were both on Broadway, close to his house. According to Ronald Peel, publican at the Napier Tavern, Johnson always turned up at the same time in the evening, stepping into the saloon bar with a brief “Good Evening” — or “Good heavening!” as Johnson himself imagines them registering his pronunciation — and then taking his customary place on a high, wooden barstool with a seat upholstered in red synthetic leather of the type Tom Waits was in those days hymning as “Naugahyde”. He allegedly always wore the same distinctive garb too: a black peaked watchman’s cap, a black leather jacket, black trousers, black leather boots, and sometimes a thin black leather tie — the same gear, in other words, that had shocked the poet and translator, Michael Hamburger, who had been astonished to find this highly regarded and sensitive writer going about in the garb of a Hell’s Angel or skinhead. (Sea View, p. 392)

“Charlie’s” bar stool

Long preserved as a relic at the Napier Tavern, the stool from which Johnson, aka “Charlie”, observed and sometimes participated in proceedings is here seen in use as a prop with Big Fish and Friends at their performance of texts from UJ’s Island Stories, Little Theatre, Meyrick Road, Sheerness, 5 March 2016.

The bedspread and the kidney machine: charity fund-raising at the Sea View Hotel

Publican Col Mason (left) handing a cheque for £184 to the chairman of the local kidney machine fund. “The Mayor is in attendance, complete with his chains, and so too is Johnson: an uncaptioned figure standing alongside the others at the back.” (Sea View, p. 401). The white object, front, was first prize in the raffle. As Johnson wrote to friends in Rostock: “Now I wanted to win that bedspread for you. Further details can be found on the two enclosed raffle tickets, and as for this white monstrosity’s weight, I will say only that the ladies’ knees buckled slightly when it was placed in their two arms for them to admire it.” The picture was printed in the Sheerness Times Guardian on 15 September 1978.

The (other) sociologist and the glass that was never raised

Johnson, may have been unaware of it, but he wasn’t the

only person investigating the Isle of Sheppey and the situation of its remaining people after the naval dockyard and also the associated army garrison and naval command (“The Nore” ) were closed in 1960. Ray Pahl, the geographically trained professor

of Sociology at the University of Kent, also started exploring the Isle of Sheppey

in the 1970s.

The (other) sociologist and the glass that was never raised

Indeed, he adopted the

island as a kind of research laboratory in which to investigate the consequences

of deindustrialisation of the kind that had destroyed the island’s economy at a

stroke. Starting out with romantic ideas of the “urban pirate” with his often

less than legal ways of “getting by”, he approached the Isle of Sheppey as a

place where the post-industrial future was already coming into view. He traced the

emergence of the “informal economy” on the island, and the replacement of the full

time male job with a more mixed form of “household economy” in which women’s

work, DIY initiatives, and sometimes nefarious

forms of “self-provisioning” featured largely.

Together w ith his Ph.D student and co-researcher, Claire Wallace, Pahl also

studied the experience and perceptions of school leavers on the island. They produced

work of abiding influence on economic and social policy – Pahl in his book Divisions

of Labour (1984) and Wallace in her later study of the “fracture” the closure

imposed on the lives and expectations of girls and boys in For Richer, For

Poorer: Growing up In and Out of Work (1987). Johnson and Pahl may never have met to compare

findings but their accounts of island life in the seventies and early eighties have

a world in common.

![]()

The Kingsferry Bridge across the Swale was built in

1960, a year in which the island economy was shattered by the closure of the

dockyard at Sheerness. An entirely practical structure, which carried trains as

well as road vehicles between Sheppey and the richer mainland to which Kent’s

reputation as the “Garden of England” has always been attached, it achieved symbolic significance for Pahl:

“Pahl’s drive over the Kingsferry Bridge was not just

a crossing from the“macro” to the “micro” level of analysis, nor, in the terms that

his PhD student and co-researcher Claire Wallace would borrow from the sociologist

Basil Bernstein, from the “elaborated” code

of middle-class language to the more practical and allegedly “restricted” code

of working-class speech. For Pahl, crossing the Swale also meant preferring

“hard, obdurate reality” against the “disembodied” theories gripping many of

his colleagues at the university. Sheppey was where Pahl would take his stand,

seeking to go beyond the vivid but far from “scientific” investigations carried

out by Mass Observation and by writers such as George Orwell and J.B. Priestley

in the Thirties. As time went on, he would also claim common cause with E.P. Thompson,

the Marxist historian and activist who asserted the case for experience, agency

and the historically dynamic nature of social class as against what he called

the “poverty of theory” [embodied by Louis Althusser and his English followers] in a blazing

English tract published in 1978.” (Sea View, p. 421)

Sheerness Times Guardian

Wherever he found himself, Uwe Johnson required newspapers. In West Germany, it might be Die Zeit or Der Spiegel. In Rome it was La Stampa. He read the New York Times in Berlin as well as during his trips to America. In England he took both the national Guardian and the island weekly, the Sheerness Times Guardian.

In the first edition on January 1858, the founder of the Sheerness Guardian, Thomas Rigg, had hailed Sheerness as an outward-looking new town that had nothing in common with parochial and tradition-bound communities on the Kentish mainland.

Unlike such backwaters, Sheerness had “scarcely any aboriginal race”. It was open to the wider world via the naval and military establishments that formed the primary reason for its existence. The town, said Rigg, was “a colony of emigrants from all parts of England, Scotland, Ireland and Wales.” And “to such a society,” so Rigg proudly declared, “the affairs of the neighbouring country are, in most cases, about as interesting as the local policy of Timbuctoo.”

More than a century later, the Sheerness Times Guardian would provide Johnson with stories —informative, moving and peculiar too — to pass on to faraway friends. It would also serve as a screen, or perhaps something closer to a crinkly net curtain, through which an unconvinced incomer might peer without giving anything away: a useful device, in other words, when it comes to keeping your perceptions “non-committal” and, as Johnson continued in a letter to Max Frisch, preventing them from ‘ascending into experience or judgement’. There was, though, an exception to be made for the Kent Evening Post (context: Sea View, pp. 452-58)

Island Music

Henry Russell, the composer of “A Life on the Ocean Wave”,: Cheers, Boys, Cheers” and many other popular songs of the nineteenth century, was born into Sheerness’s Jewish community in 1812.

Yet the island’s music had changed by the 1970s. As Johnson is likely to have discovered from the pages of the Sheerness Times Guardian, Michael “Natsy” Contant was one of the very first to introduce Caribbean steel bands to Britain and Europe. Having come from Trinidad as a tuner with the Dixieland Steel Orchestra in 1960, he lived for many years at 7 Delamark Road in Sheerness, tuning pans on a stretch of waste ground beside Kingsferry Bridge and, with his classically trained wife Carol and their children, forming the Rainbow Steel Band, which regularly presented “music of the Caribean” on the island as well as elsewhere in Britain and Europe. Their “hauntingly beautiful” sound, and especially their arrangement of Richard Addinsell’s “Warsaw Concerto”, appears to have been particularly popular with Sheppey audiences.

— “Love My Life” Robbie Williams’s day at Shellness

Henry Russell, the composer of “A Life on the Ocean Wave”,: Cheers, Boys, Cheers” and many other popular songs of the nineteenth century, was born into Sheerness’s Jewish community in 1812.

Yet the island’s music had changed by the 1970s. As Johnson is likely to have discovered from the pages of the Sheerness Times Guardian, Michael “Natsy” Contant was one of the very first to introduce Caribbean steel bands to Britain and Europe. Having come from Trinidad as a tuner with the Dixieland Steel Orchestra in 1960, he lived for many years at 7 Delamark Road in Sheerness, tuning pans on a stretch of waste ground beside Kingsferry Bridge and, with his classically trained wife Carol and their children, forming the Rainbow Steel Band, which regularly presented “music of the Caribean” on the island as well as elsewhere in Britain and Europe. Their “hauntingly beautiful” sound, and especially their arrangement of Richard Addinsell’s “Warsaw Concerto”, appears to have been particularly popular with Sheppey audiences.

— “Love My Life” Robbie Williams’s day at Shellness

Yet the island’s music had changed by the 1970s. As Johnson is likely to have discovered from the pages of the Sheerness Times Guardian, Michael “Natsy” Contant was one of the very first to introduce Caribbean steel bands to Britain and Europe. Having come from Trinidad as a tuner with the Dixieland Steel Orchestra in 1960, he lived for many years at 7 Delamark Road in Sheerness, tuning pans on a stretch of waste ground beside Kingsferry Bridge and, with his classically trained wife Carol and their children, forming the Rainbow Steel Band, which regularly presented “music of the Caribean” on the island as well as elsewhere in Britain and Europe. Their “hauntingly beautiful” sound, and especially their arrangement of Richard Addinsell’s “Warsaw Concerto”, appears to have been particularly popular with Sheppey audiences.

— “Love My Life” Robbie Williams’s day at Shellness

St. Sexburgha’s Abbey: Minster-on-Sea:

INTERWININGS

The Transnational Landscape:

Ahrenshoop, Fischland and Shellbeach, Sheppey

“Fischland is the most beautiful place in the world.”

— Gesine Cresspahl in Anniversaries IV

On Sheppey, the Englishman isn’t always an Englishman and his home is definitely neither a castle nor a stately home raised on colonial extraction or slavery. “Bungalettes”at Shellbeach.

Two Island Resorts

1. Leysdown-on-Sea

“We

can all agree that Britain’s coast has been trashed. Yet has it ever been so

sedulously trashed as on Sheppey? Leysdown on the northeast corner of that isle

is terminal England, the last resort, the nadir of bungalow development. It makes Hayling look like Biarritz...”

— Jonathan Meades, “Last Resort” (1991)

“The bricolage and inspiredly untutored inventiveness of most early twentieth century plotlands is missing. On the shore, half a mile from the village’s centre, there are asbestos and wooden hutments, endlessly buffeted by the howling easterly. Bent bushes try to smother them.” (Meades)

“Leysdown on Sea is the ancestral dreamsite of a Lost Tribe: all the aboriginal cockney characteristics, celebrated in fiction and in song, have migrated here – and have been buried alive in pitches of caravans, mobile homes, wooded sentry boxes (inner-city privies), and upturned tin boats, veterans of Dunkirk.” (Iain Sinclair, Downriver (1991, p. 397).

Out-of-season objectors aside, Squeeze’s song “Pulling Mussels from the Shell” (1980) was inspired by nostalgic memories of family holidays at Leysdown. Here it is, accompanied by footage from Seaside Heights, New Jersey.

Regeneration: Heavy Lifting by Artists (2009-2013)

“Leysdown-Rose-Tinted”

2. Prora

Whatever may be said about the laissez-faire mess that is Leysdown-on-Sea, it was never as dismal as the colossal resort of Prora, built in the late Thirties as part of the Nazi government’s “Strength through Joy” initiative. Conceived as one of five vast “Sea Baths” proposed for workers following the destruction of Germany’s trade unions, it consists of a series of huge six-floor concrete blocks placed along the 4.5 kilometre length of a magnificent Baltic beach on the spit connecting Sassnitz and Binz on the eastern coast of the Pomeranian Island of Rügen.

Robert Ley, the Nazi head of the German Labour Front (Uwe Johnson allows him a brief appearance in Anniversaries as a “drunken pig”), imagined Prora as a Nazi answer to Butlins that would provide compliant workers with a week of indoctrinated leisure. Every room would have a sea view. There would be cinemas, swimming pools, canteens and, at Hitler’s insistence, a central arena in which twenty thousand joyful workers could be addressed as a concentrated Sieg Heiling mass.

In 1991 this never-completed line of Aryan barracks (construction was interrupted by the outbreak of war in September 1939) emerged from GDR military control as a set of disconcerting ruins. When we last visited the site, some of its reinforced concrete was acquiring an unexpectedly luxurious shine. The developers who had bought some of the blocks, themselves now listed for conservation, were bringing them to new life, although not as the centre for refugees that some critics have suggested might be appropriate. Two-bedroom apartments with new balconies were being offered at €600,000 and upward.

The Investor shipwrecked.

One Window: Two Ships

“It all revolved around the view. It was the view that was appropriated.”

— Uwe Johnson, on Riverside Park, “A Part of New York,” 1968

— Uwe Johnson, on Riverside Park, “A Part of New York,” 1968

“It may be not merely egotistical if I describe to you some views to be seen over the course of a few afternoon hours. Views, namely, out the window, and I wish you could have seen them: the two of us, next to each other, right in front of the house, where the poorer folks from London enjoy disporting themselves on a Sunday like this one, as tourists by the sea, visible only from the waist up to me and my dear wife Mrs. Letsnotdiscussit, and yet still a valuable warning about the lack of, or taste in, leisure attire. Following them come the waves of the River Thames, sea-like here, beating against the stones as high or as low as the Royal Geographical Tidal Institute’s calendar permits them to. For an ignorant observer such as myself, they are merely bright white a long way out, a little dirty-looking but choppy in any case; the last third of my visual field, though, is as blue as blue can be, magnificently changeable, from pale to gray to strapping within this color. Within and atop this blue, what is there to say to a lady from Königsberg: bathers in various stages of suffering from sunburn, boats with sails in fashionable colorations, some of them even classified and many of them well-suited to offer me certain memories, silent but critical, pertaining to the process of jibing. People paddling, those who let themselves be brought hither and thither by petrol engines, and on the horizon, where cartography would suggest that we should be able to detect the south coast of Essex, merely a difference: not a line, a smudge between water and sky, that educated people label as a horizon and which is therefore mine. And I’ve almost forgotten to admit to you the rude British Petroleum oil tanker that just now went pitching from right to left, from east to west, across the window — probably because I believe I share your opinion of such objects in one’s field of view.”

— Uwe Johnson, Letter to Hannah Arendt, 8/3/1975

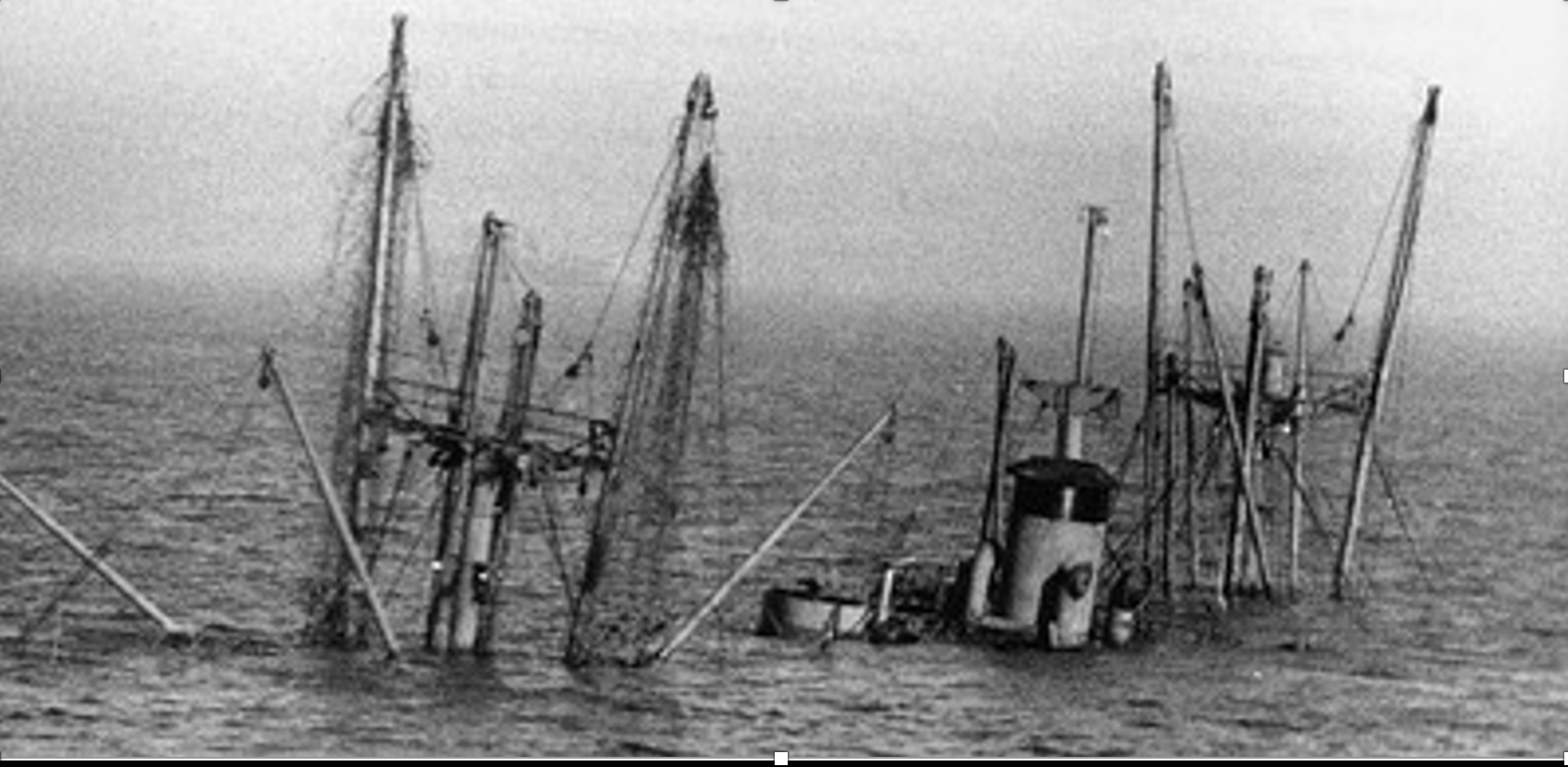

The SS Richard Montgomery:

“What is that thing?”

“In the Thames, about two miles off the north coast of the Isle of Sheppey, a cluster of parallel diagonal poles catches one’s eye. They are visible especially at low tide, but also when the tide is eighteen feet higher, because behind them tosses and pitches almost ten miles of the water’s surface as well as, since the Essex coast in the distance quite noticeably veers off to the north, the horizon line under the quickly shifting illuminations of the sky. Whoever moves here to the town of Sheerness, on the northwest corner of the island, is struck by the reflections of the light in the multiply moving mouth of the Thames and North Sea, and at first he thinks those poles are fish traps, blown into a diagonal position by a ferocious west wind, since the eye is easily fooled about distances when looking out across a boundless body of water; the black triangle that becomes visible between the poles at ebb tide can easily be taken for a fishing boat with underlying property rights. Whoever has moved here and has decided he is in need of binoculars will find himself losing faith in those fish traps, since for two weeks they are not moved once, and furthermore the poles are of unequal length, and in a strangely regular relationship with one another, and located too close to the central waterway. What is that thing?”

— U.J. “An Unfathomable Ship” (1979)

“Our one sight worth seeing”

“Either we’ll go down wet, or we’ll go up in a fireball”

The Explosion

“An explosion of this mixture will be among the largest in human memory, if you leave aside the nuclear ones. If you take the Richard Montgomery as the centre of a circle with a radius of two miles, the first land to be hit will be the northwest corner of the island, with the town and port of Sheerness. The older buildings and unreinforced walls will collapse, and the gas and water pipes will shatter. Within a radius of seven miles, broken glass and the collapse of any wobbly chimneys or loose roofs are likely. That circle includes half of the town of Sittingbourne, as well as the oil port and refinery complex on the Isle of Grain, west of Sheppey. The detonation may cause a fireball whose air pressure will fling heavy objects and debris more than a mile, perhaps into one of the supertankers with a hundred thousand tons of oil in its belly. (The Richard Montgomery lies near the extremely busy shipping channel of the Thames. A few miles farther north, Her Royal Highness’s Ministry of Defence maintains and runs a naval artillery range in the ocean, whose detonations reach the windows of Sheerness like fist blows.) A simultaneous explosion of the whole cargo will cause a tidal wave to rush up the Medway and Thames rivers, destroying additional settlements near the banks. At low tide, the effects would be multiplied, due to there being less water to absorb the shock. The ultimate extent of the damage will be determined by the weather. Any heavy, low-lying cloud cover above the exploding cargo of bombs will bounce back ascending shock waves and the multiple ricochets will reach Canvey Island, ten miles upstream, where they will hit storage tanks with a holding capacity of almost forty thousand barrels of oil as well as chemical and methane gas containers. A chain reaction or domino effect could produce damage in the eastern suburbs of London, to a greater or lesser extent. It is unlikely that the House of Commons or Whitehall would be affected.”

— UJ “An Unfathomable Ship”

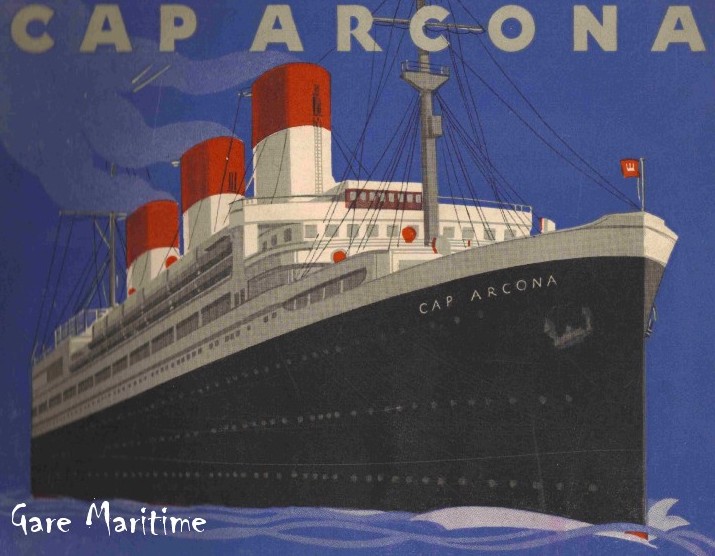

The Cap Arcona

Many other such maritime explosions have been brought to mind by people trying to come to terms with the devastation threatening the Thames estuary from the SS Richard Montgomery. Local examples included the battleship HMS Bulwark, which exploded when moored off Sheerness on 26 November 1914, disappearing in a few seconds, with a loss of 741 men; and also the minelaying liner HMS Princess Irene, which went up killing 352, many of them local dockyard workers, in another disaster six months later. As will be known to readers of Anniversaries III, the exploding ships at the back of Johnson’s mind as he looked out on the masts of the Richard Montgomery, included one that took its name from the northernmost point of the Baltic island of Rügen.

By 1927, the chalky headland and lighthouse called Cap Arkona had given rise to an ocean-going liner: built and launched that year for the Hamburg-South American Line”, the SS Cap Arcona was a “floating palace” that became famous as the fastest most luxurious ship on the route for Latin America. Requisitioned during the Second World War, it was used as a barrack at the Baltic port of Gotenhafen, now restored to Poland as Gdynia. By the last days of the war in 1945, its engines had been burnt out during three desperate voyages shipping Germans west from the Russian advance, and it was moored in Neustadt Bay, not far from Lübeck. As Allied forces approached from the West, prisoners from various abandoned concentration camps were crammed aboard the Cap Arcona and other ships including a cargo vessel named the SS Thielbeck, and left to whatever dire fate awaited them.

As Johnson writes, “Freedom came across the bright sunny bay on May 3 in the shape of a squadron of British bombers.” Actually Typhoon fighter bombers from four squadrons were involved in the operation. They used rockets to sink the Cap Arcona and Thielbeck, along with several other undefended ships, and then came back to machine gun survivors

![SS. Cap Arcona, 1948]()

in the water. Those who survived that second assault, faced the prospect of being murdered by SS and other killers if they made it onto beaches at Timmendorfer, Priwall and Travemunde.. Between seven and eight thousand people of thirty differtent nationalities are said to have died. Corpses would turn up on scattered beaches for decades to come. Long before Remembrance Day was drafted into the service of Brexit, survivors had noted — with various degrees of anger and dismay — that the Cap Arcona disaster has not been allowed to disturb British commemoration of the Second World War.

The Sheerness Wall

Johnson knew the Berlin version well, but his last months were plagued by the construction of a very different wall directly across the road from his window.

“I have, no doubt, let fall a word or two about the inexorable pollution and impoverishment of the city of Sheerness. Now I am obliged to add the fact, impossible to make up, that the offices of Southern Water intend to protect this grimy, insignificant locale by raising the flood wall even higher in front of this row of houses. Preceding this undertaking must necessarily come the removal of the existing embankment with all its garages, storerooms, and the concrete wall on top, that is, a to and fro of heavy machinery from excavators to the wading crane with its fat cement noggin. As a result, Southern Water has sent representatives of a sworn surveyor’s firm into every house to determine and record its architectural condition in anticipation of the claims they expect from residents as a consequence of the demolition and reconstruction. In other words, we have to reckon with the chance of collapsing walls, likewise of cracking windows. I mention all this in no way expecting that it will make me feel better to complain (a hypothesis all too amply disproven), but merely to discourage you for a time, say two years or so, from asking how I’m doing. You will know the answer already: Aggrieved.”

— Uwe Johnson, letter to Burgel Zeeh, 26 August 1982

![]()

Built by Southern Water along the full length of Marine Parade in 1983-4, Sheerness’ new Sea Defence Wall was higher than its oredecessor, but it was not build without some aesthetic effort. The engineers recognised the difficulty of integrating a high concrete rampart with the 19th century buildings that would be facing it from across the street. They consequently hired the architectural firm of Garnham Wright Associates, to design a “rusticated” surface that might help their colossal barrier settle into the increasingly flood-prone town.

The trade journal Cement and Concrete Quarterly celebrated Garnham Wright’s design, commending the playfulness with which the architect proposed a seaside form of English pop art. Johnson, however, hated it. A few months before he died, in February 1984, he told his artist neighbour, Martin Aynscomb Harris, that the still unfinished “rusticated” and graffiti-resisting rampart reminded him of the works of Hitler’s preferred architect, Albert Speer.

![]()

![]()

Vehicle passing shutters in the room that was once Johnson’s basement office